Each day as part of the Great British Innovation Vote – a quest to find the greatest British innovation of the past 100 years – we’ll be picking one innovation per decade to highlight. Today, from the 1910s, the birth of Crystallography.

Science Museum curator, Boris Jardine, explains via an audioboo why he thinks Crystallography is the greatest British Innovation, and visitors to the Museum can see some examples of the work of X-ray crystallography in a new display case, Hidden Structures.

To paraphrase the great x-ray crystallographer Max Perutz: it’s even told us why blood is red and grass is green. ‘It is’ said Perutz ‘the key to the secret of life’.

Our understanding of the structure of compounds – from the ordered crystal structure of table salt and diamonds to the complex organic compounds that make up life – was only possible through the discovery of X-ray crystallography a century ago.

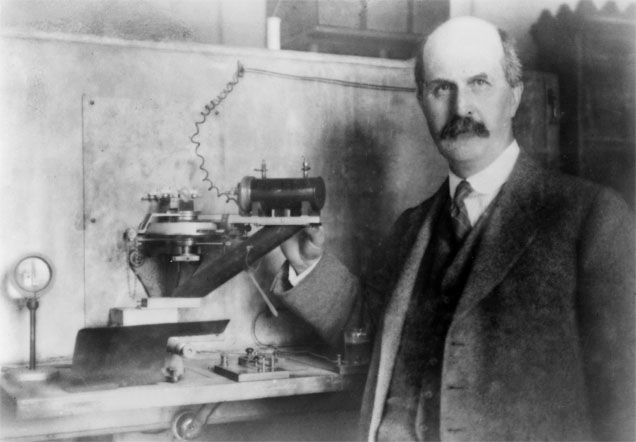

Father and son physicists William and Lawrence Bragg exposed crystals to X-rays, recording and interpreting the resulting image, the X-ray diffraction pattern, to predict the atomic structure of the crystal. For this, Bragg and his son won the Nobel Prize (at 25, Lawrence Bragg became the youngest ever Nobel Laureate) and X-ray crystallography remains to this day the most accurate method of determining the atomic structure of materials.

Crystallography has allowed innumerable advances in chemistry, physics and medicine, and it deserves your vote as the Greatest British Innovation. Click here to vote.