Ahead of November’s opening of the Collider exhibition, Content Developer Rupert Cole takes a look at the story behind the Geiger counter

“The excitement is growing so much I think the Geiger counter of Olympo-mania is going to go zoink on the scale!”

Thus spoke Boris Johnson in his London Olympics opening speech a little over a year ago. The author of several popular histories including Johnson’s Life of London, is it conceivable Mayor Boris knew the Olympic summer coincided with the 104th birthday of the Geiger counter…?

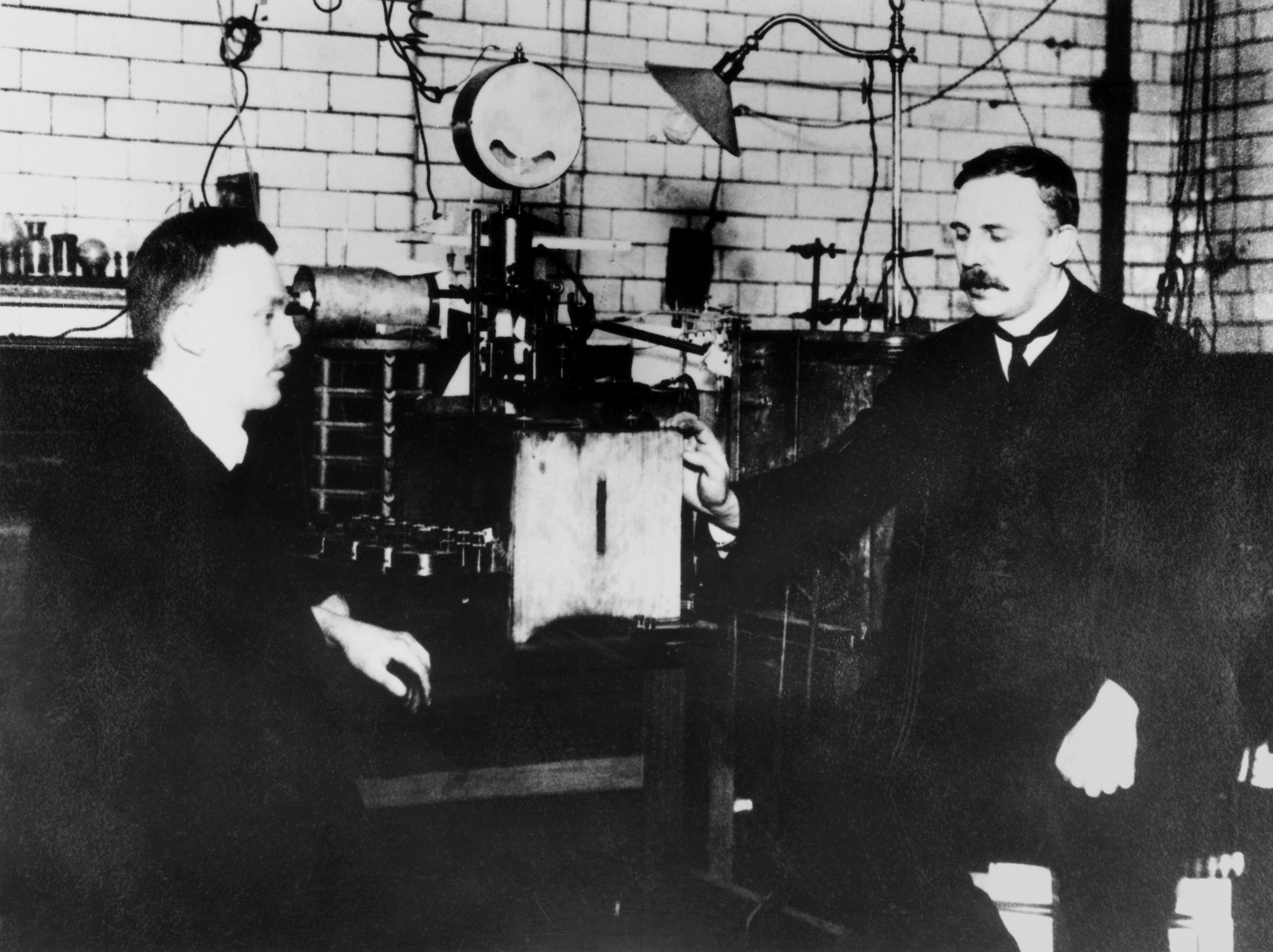

On this day, 105 years ago, Hans Geiger and Ernest Rutherford published their paper on a revolutionary new method of detecting particles.

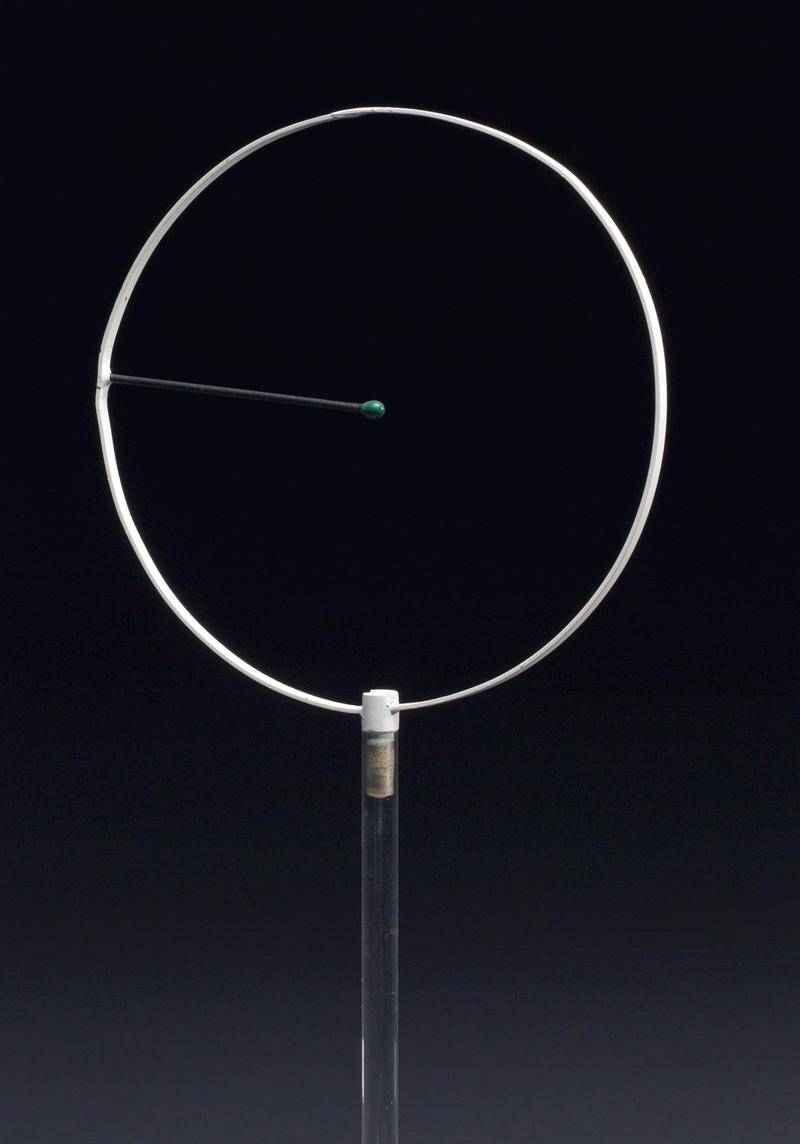

The first generation of Geiger counters did not produce the characteristic click we know and love today. Instead, an electrometer needle would suddenly jump, indicating an alpha particle had been detected.

They worked by picking up electric signals given off by electrons, which had been stripped from gas molecules by passing alpha particles. The beauty of them was that they provided another way to measure radiation, verifying the laborious and blinding method of counting light scintillations.

Once the technology improved, Geiger-Muller counters (as the later ones were called) became extremely nifty particle detectors, essential hardware for any cosmic-ray physicist. They are now used for many different purposes, from airport security to checking the levels of radioactivity in certain museum objects.

For a long time the device was just a tool used by researchers of radioactivity, an innovation that made Geiger’s task of counting by eye emissions of alpha particles from radium a little easier.

This is not to deny Geiger’s eyes were very effective counters of tiny flecks of light – produced by individual alpha particles as they hit a fluorescent screen. As Rutherford said at the time:

“Geiger is a demon at the work of counting scintillations and could count for a whole night without disturbing his equanimity. I damned vigorously and retired after two minutes”.

Arriving in Manchester in 1907, the German-born Geiger clearly was responsible for the nitty gritty side of the research. Ernest Marsden, a twenty-year old undergraduate, joined the pair the following year. The young student may not at first have realised that he was contributing to one of the most remarkable discoveries of the century.

In a darkened lab, Geiger and Marsden would take turns to count the sparkles of alpha particles as they hit a screen, having been fired straight through a sheet of gold leaf.

As the particles were much smaller than the gold atoms, it must have seemed slightly barmy when Rutherford suggested to move the counting screen behind the radium source and look for scintillations there.

The near-blind researchers hit gold, so to speak, and found the odd alpha particle had bounced back. Rutherford declared it the most incredible event of his life, “as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

The team discovered the atoms had a nucleus – a miniscule core that caused the occasional alpha particle to rebound. Rutherford would soon come up with an entirely new picture of atoms, which depicted electrons orbiting around this central nucleus.

Geiger recalled the glory moment: “One day (in 1911) Rutherford, obviously in the best of spirits, came into my room and told me that he now knew what the atom looked like”.

You will have the chance to see up close Rutherford and Bohr’s atomic model, and discover the objects that helped shape modern physics in Collider, a new exhibition opening this November.