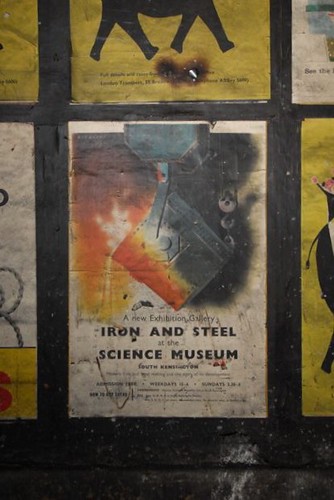

My attention was drawn last week to an incredible set of photographs taken recently in Notting Hill Gate underground station, during refurbishment. They show a deserted passageway sealed up in 1959, with advertising posters surviving untouched to this day:

The full set, by London Underground’s Head of Design and Heritage, Mike Ashworth, are on Flickr. One of them advertises the Science Museum’s then-new Iron and Steel gallery, depicting a Bessemer steel converter in mid-pour:

I’ve spoken before (in posts about Barrow-in-Furness and Bessemer) about our 1865 converter. It’s now in Making the Modern World but back in the sixties it was in Iron and Steel, as shown here:

(Hand-held audioguides aren’t a recent museum phenomenon. We were trying them out in the sixties!)

In front of the converter you can see a flattened metal ring. It’s a section of round gun barrel, squashed flat by a steam hammer. It was done cold, and there’s no cracking.

It was a demonstration carried out by Bessemer in 1860 to show the superb ductility (flexibility) of his steel, which made it such a useful material – giving us longer bridges, bigger ships, taller buildings, stronger machinery and rails to take heavier and faster trains. You can see it in Making the Modern World, too.

Iron and Steel was replaced in 1995 by our current Challenge of Materials gallery.

(Thanks to Mike Ashworth and London Underground for sharing their pictures.)

5 comments on “Liquid Steel And An Underground Time Machine”

Comments are closed.

Thanks for this wonderful post, especially the poster which is actually of a transfer ladle and not a bessemer converter. The Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining headquarters in London also has a large collection of Sir Henry Bessemer’s belongings including his original patent drawings and portraits.

Jackie Butterfield BEng CEng MIMMM

Iron and Steel Society Co-ordinator, the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining

Many thanks for your comment, Jackie. Apologies for the slip-up on the ladle. Very best wishes, David.

Hello all

I’m really glad so many people have enjoyed seeing this wonderful poster – I think it is one of the best commercial images shown in the set that have survived at Notting Hill Gate station and I only wish I knew the artist. It’s also great to see that it has added to the history and story of the Museum itself!

Jackie – I recall many years ago when I was curator & librarian at the Scottish Mining Museum utilising the Institute’s wonderful collection – you should Flickr some of the great items the collection has!

Mike Ashworth

Design & Heritage Manager

London Underground

Hello Mike – many thanks for your comment. I spent a little while down in our archives yesterday to see if I could find out more about the poster and its artist, but to no avail. The info may well be buried away somewhere, but it would take me some time to find it, I fear. If I do find anything, I’ll be sure to post an update! Kind regards, David.

Fascinating post – just picked it up as I am doing some background research, which may ultimately appear as a book.

The year after the 1865 converter first appeared, apparently eighteen 5-ton beasts were in operation at Barrow Haematite Iron & Steel Works. Presumably at this point this would make them the first commercially viable steelmaking (by the Bessemer process) in the world.

Barrow has long neglected its iron and steelmaking heritage, with so much focus on the industries, such as shipbuilding, that came along later.

At least 3 generations of my family, including myself worked at the plant in its later days, and into British Steel.