Ahead of November’s opening of the Collider exhibition, Content Developer Rupert Cole explains how beer was used for cutting-edge particle physics research.

Late one night in 1953, Donald Glaser smuggled a case of beer into his University lab. He wanted to test out the limitations of his revolutionary invention: the bubble chamber.

Previously, Glaser had only tried exotic chemical liquids in his device. But now his sense of experimental adventure had been galvanised by a recent victory over the great and famously infallible physicist Enrico Fermi.

Fermi, who had invited Glaser to Chicago to find out more about his invention, had already seemingly proved that a bubble chamber could not work. But when Glaser found a mistake in Fermi’s authoritative textbook, he dedicated himself to redoing the calculations.

Glaser found that, if he was correct, that the bubble chamber should work with water. To make absolutely certain he “wasn’t being stupid”, Glaser conducted this curious nocturnal experiment at his Michigan laboratory. He also discovered that the bubble chamber worked just as well when using lager as it had with other chemicals.

There was one practical issue however, the beer caused the whole physics department to smell like a brewery. “And this was a problem for two reasons,” Glaser recalled. “One is that it was illegal to have any alcoholic beverage within 500 yards of the university. The other problem was that the chairman was a very devout teetotaler, and he was furious. He almost fired me on the spot”.

On 1st August 1953, 60 years ago this Thursday, Glaser published his famous paper on the bubble chamber – strangely failing to mention the beer experiment.

Glaser’s device provided a very effective way to detect and visualise particles. It consisted of a tank of pressurised liquid, which was then superheated by reducing the pressure. Charged particles passing through the tank stripped electrons from atoms in the liquid and caused the liquid to boil. Bubbles created from the boiling liquid revealed the particle’s path through the liquid.

One of Glaser’s motivations for his invention was to avoid having to work with large groups of scientists at big particle accelerators. Instead, he hoped his device would enable him to study cosmic rays using cloud chambers in the traditional fashion; up a mountain, ski in the day, “and work in sort of splendid, beautiful surroundings. A very pleasant way of life – intellectual, aesthetic, and athletic”

Ironically, as the bubble chamber only worked with controlled sources of particles, it was inherently suited to accelerator research, not cosmic rays. Soon the large accelerator facilities built their own, massive bubble chambers.

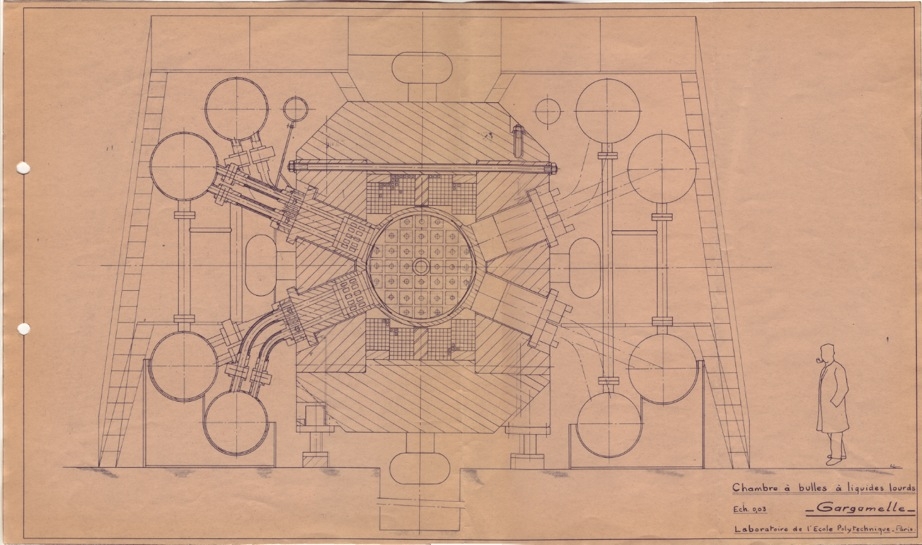

Between 1965-1970 CERN built Gargamelle – a bubble chamber of such proportions that it was named after a giantess from the novels of Francois Rabelais (not the Smurfs’ villain). Gargamelle proved a huge success, enabling the discovery of neutral currents – a crucial step in understanding how some of the basic forces of nature were once unified.

This November you’ll have the chance to see up close the original design drawings for Gargamelle, and much more in the Collider exhibition.