In December 1965 Sergei Pavlovich Korolev was finally put in charge of the Soviet Union’s manned lunar programme. He would go on to lead its two projects: one to fly a cosmonaut crew around the Moon; the other to land one on the surface.

The nation’s secret assault on the Moon – a delayed response to President Kennedy committing the United States to do the same – had already faced huge challenges: insufficient funding; competing schemes and design bureaux; poor organisation.

But many felt that if anyone could pull off the seemingly impossible it would have been Korolev: the man who had steered the Soviet Union into space with a string of firsts between 1957 and 1965 – the first artificial satellite (Sputnik), first animal in orbit (Laika, a dog), first man in space (Yuri Gagarin), first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova), first multiple crew and the first space walk (Alexei Leonov).

He had never been publicly named during these glory years, known only as the Chief Designer.

He was a remarkable man: a first-rate engineer, designer, and quite a brilliant manager who ran much of the Soviet missile industry and most of its space sector.

He also knew how to get the best out of large numbers of workers in many different institutions and keep his political masters in the Kremlin happy.

His iron will, determination and energy were remarkable – it had helped keep him alive during the dark days of his imprisonment in the Gulag in eastern Siberia.

In 1938, while listening to a new gramophone record with his wife in their Moscow apartment, there was a knock on the door and the secret police came in to ransack their rooms.

He was taken away and accused – falsely – of sabotage against the state.

This was the period of Stalin’s notorious purges when any perceived internal threat to the Soviet Union resulted in imprisonment at best and execution at worst.

Korolev survived his ordeal in the Gulag but many of his rocketry peers did not.

…

Vasily Mishn was appointed Chief Designer after Korolev’s death in January 1966. He too was a great engineer but without the drive and courage of Korolev.

Last year Alexei Leonov – the first man to walk in space – told me when visiting the Science Museum that in his opinion, the Soviet Union, even had Korolev lived, would not have landed on the Moon before the US.

But he added that Mishin’s hesitation to send a cosmonaut crew around the Moon would not have been Korolev’s way.

Korolev, Leonov reckons, would have launched a crewed mission and perhaps beaten the Americans in doing so.

As it was, the Soviet’s unmanned Zond 5 spacecraft in September 1968 became the first to fly around the Moon and return safely to the Earth. A menagerie of small creatures and plants were on board including two tortoises.

Three months later the Americans’ Apollo 8 spacecraft repeated the feat but this time with a human crew of three. Within months the Americans trumped this when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first footsteps on the lunar surface.

Who knows what might have happened had the Soviets beaten the Americans in going round the Moon? History may have followed an entirely different trajectory.

Korolev’s anonymity came to an end immediately after his death. He was given a state funeral and his ashes interred in the Kremlin’s walls.

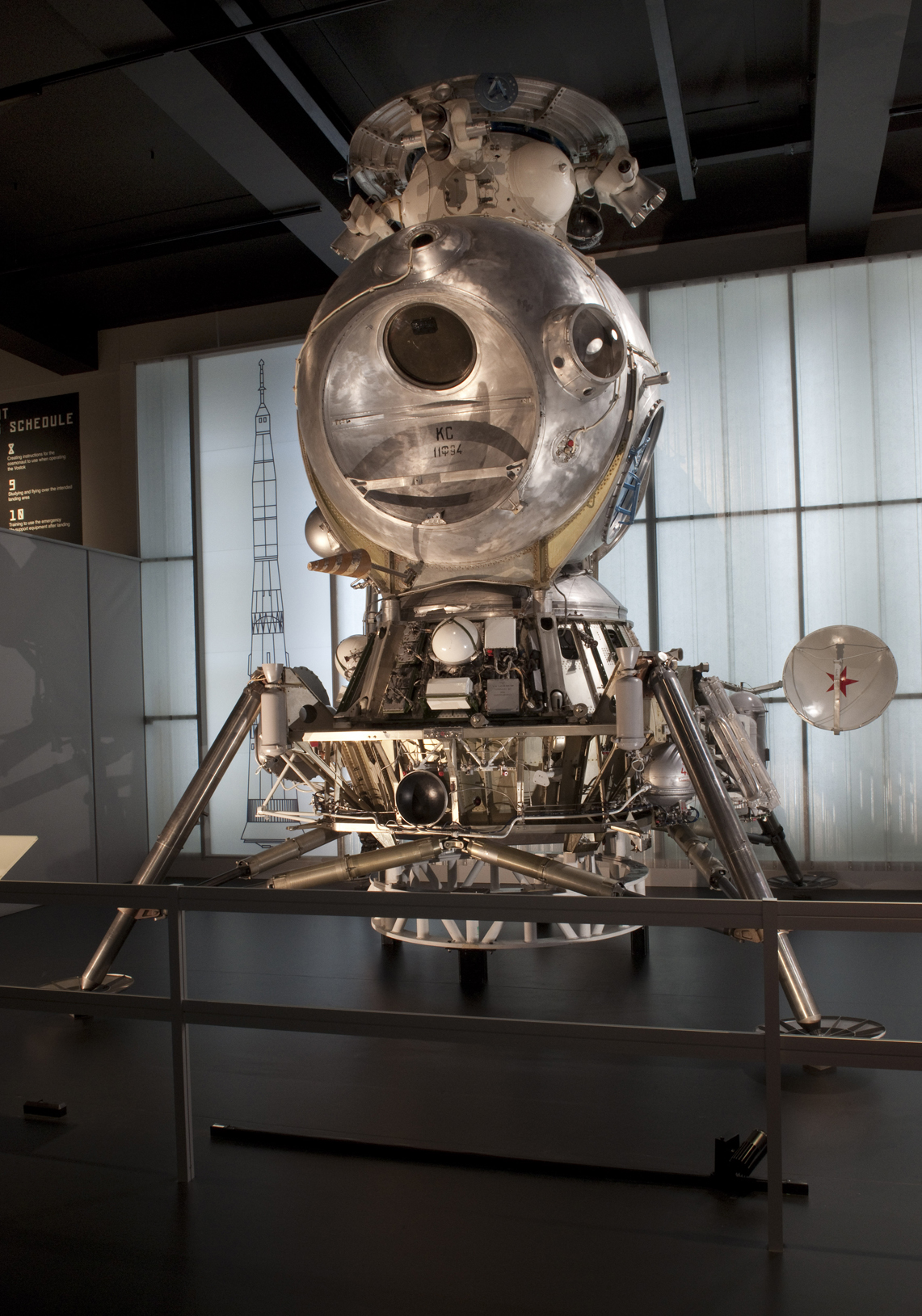

This post was originally published to accompany Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age a Science Museum exhibition that closed in 2016.

4 comments on “The father of the space age”

Comments are closed.

i visitied the exhibition recently and bought a couple of books afterwards – Red Moon Rising being one. What a man Korolev was! So good that he is getting recognition via the show… the Russian missile/space programme really was incredible and overlooked. With very little in the way of resources they achieved so much. Korolev changed the world with his risk to launch Sputnik.

Korolev seemed to occupy a very unique position in the early years of the space age. I can’t think of a direct equivalent in the American programme – he was involved in every aspect from the boosters, through the spacecraft design and cosmonaut selection and even acting as ‘capcom’ on some missions. All this while still pushing forward space policy and trying to win support from the military and politicians.

It was very clear listening to Leonov at your recent event that the cosmonauts loved and trusted him – to say they would go to the ends of the Earth for him seems an understatement!

I appreciate Leonov’s feeling regarding the circumlunar missions, but many others including Kamanin (head of the Cosmonaut corps) were against a manned mission – it wasn’t Mishin’s call. I suspect though that Leonov believes Korolev could have solved the problems that led to early failures in the Soyuz and Zond programmes making a circumlunar mission more feasible pre-Apollo 8 rather than just making a different decision in late ’68.

It’s amazing to look at how far Korolev’s star had fallen with Khruschev by the early 60’s given how capable (and proven) he was in comparison to Chelomei. Had he been given the budget and support for the lunar programmes from the start things could have been very different.

It is so amazing as to what brilliant scientific minds can achieve in this world with purely just imagination and innovation

The Soviet’s propaganda posters were fantastic. Love this one.