How about this for a sound business proposition? You spend £25 million excavating a 1‑kilometre tunnel and a cavern the size of the Royal Albert Hall deep inside a solid-rock mountain. At the same time you create an artificial reservoir with the capacity of 4000 Olympic swimming pools way up high on a barren Scottish mountainside.

Then you install four giant turbines inside the mountain so that the water from the reservoir can flow through and generate electricity for the national grid. The result of all your hard work and expense is a hidden hydroelectric power station that actually consumes more electricity than it produces.

Well, that’s exactly what the people behind the Cruachan dam and power station did… and it’s still working for us, 50 years later.

Originally devised by British engineer Edward McColl, Cruachan was the first high-head reversible pumped-storage hydroelectric power station in the world. Water stored behind the dam in the high-level reservoir has potential energy.

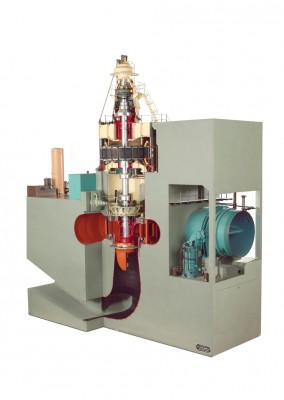

When electricity is needed, the water flows into pipes, creating kinetic energy, and rotates four Francis turbines connected to generators, producing up to 440 MW of electrical energy.

The water is then released into one of Scotland’s most inspiring sites of natural beauty, Loch Awe, 390 metres below the reservoir. The pumps that transfer water back up to the dam are the same turbine blades spun in reverse and powered by electricity from the National Grid.

Opened by HM The Queen on 15 October 1965, Cruachan is celebrating its 50th anniversary of storing energy ready for rapid generation of electricity when it’s required at peak demand.

As a story of technological achievement in 1960s British civil engineering, it ranks right up there with Sizewell A nuclear power station and the construction of the M1 motorway.

This is a story of ‘green’ power storage and production: there is no burning of fossil fuels in generating the electricity, no use of chemicals and no toxic waste, just clean water and the power of gravity. But how green is it really?

It takes more electricity to pump the water uphill than it produces on the way back down, and the energy the power station buys comes mostly from coal, gas and nuclear power stations (although the energy bought may not have been used otherwise, so this reduces waste). Also, the 200,000 tons of concrete used to construct the dam and the 220,000 cubic metres of rock excavated left behind their own huge carbon footprints.

As well as the environmental costs, the financial and personal costs during construction were significant: the project cost £25 million in 1965 and the lives of 36 men were sadly lost during the difficult process of construction. No matter how much they are hidden, the dam, administration block and 275 kV transmission lines inevitably leave their mark on this otherwise picturesque landscape.

As a business prospect, however, Cruachan makes sound financial sense. The power bought from the grid to run the pumps at night costs next to nothing. It is sold back when demand is at its highest and electricity at its most expensive, for example when people switch on their kettles after coming home from work. Buy low, sell high.

Importantly, no other commercial form of power generation can be brought on grid faster; the energy is ready, literally on tap. The generating units can be switched on from a standing start in less than two minutes, and from standby to fully operational takes less than 30 seconds. They can then be turned off instantly. In contrast, to do the same gas takes hours, coal takes days, and nuclear power stations run on cycles lasting one to two years.

The power station at Cruachan is an incredible feat of civil engineering and a monument to 1960s Scottish architecture. Deep in the heart of the mountain it can generate a whopping 7 GWh of electricity from its watery stores, so that we can all have access to instant electricity at times of peak demand, with minimal environmental impact. This week, the team at the Cruachan power station are rightly proud to be celebrating 50 years of operation and some of the best of British innovation and ingenuity.

Dr Oliver Carpenter is the Associate Curator for Infrastructure and the Built Environment.