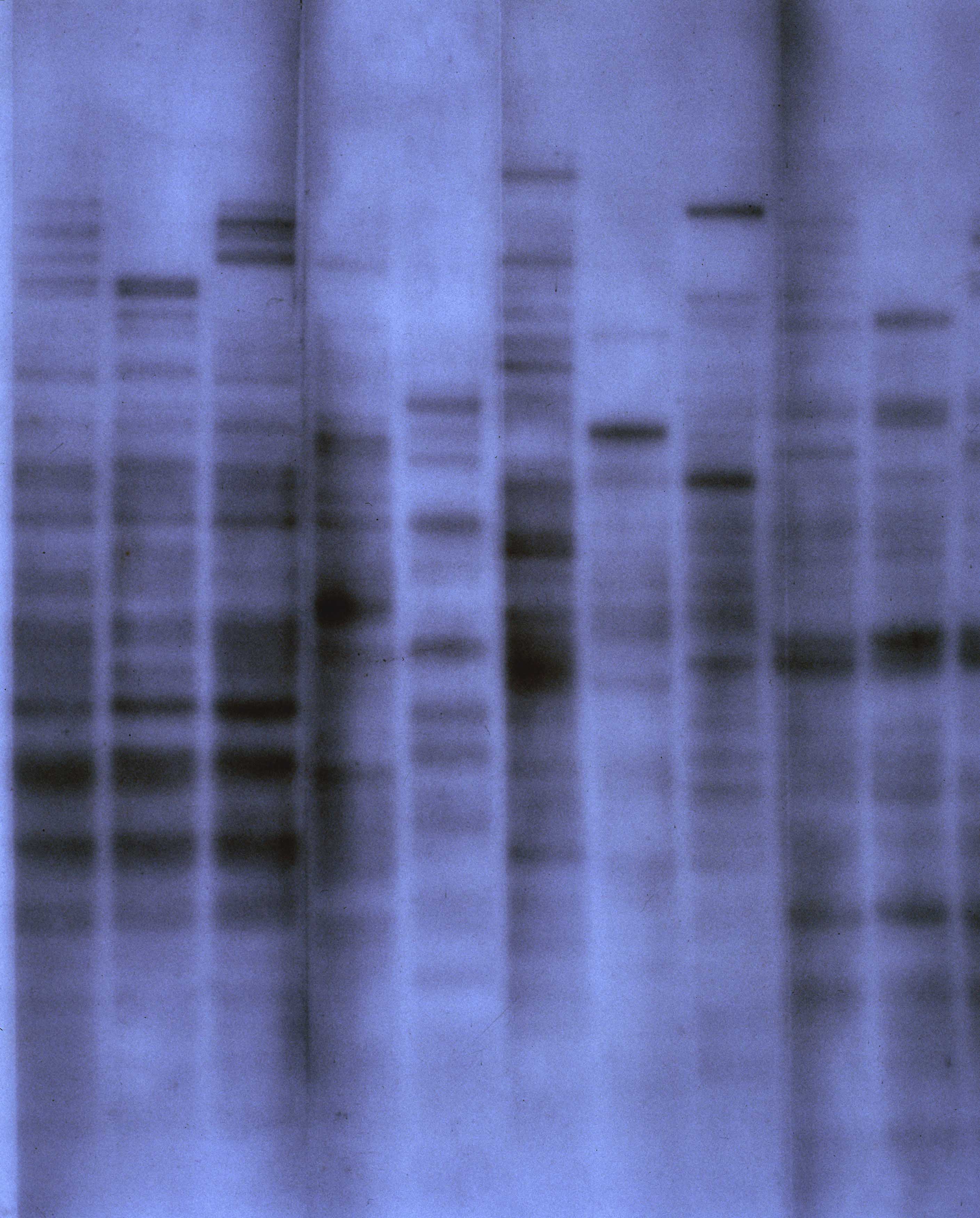

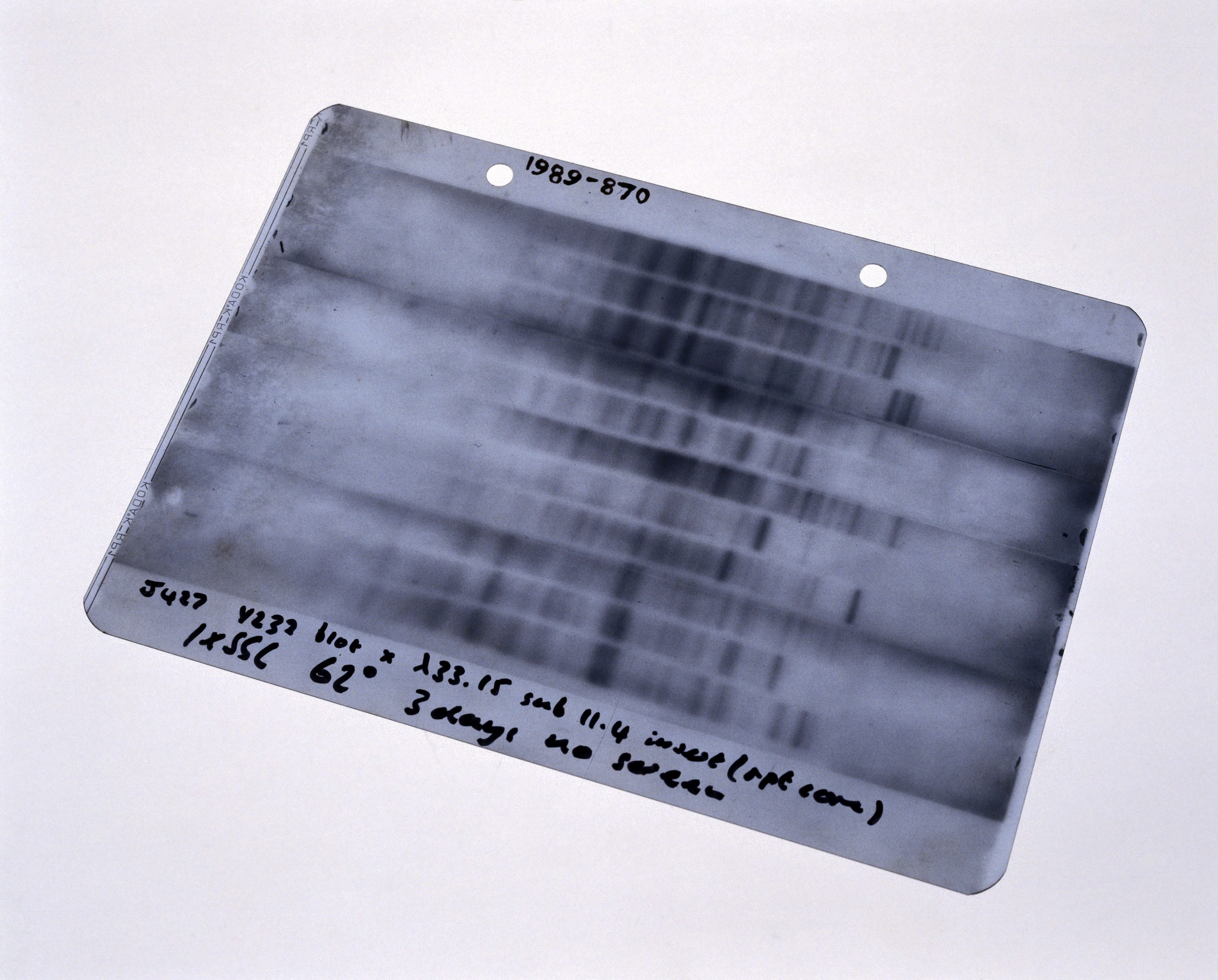

This fuzzy image, taken on 10 September 1984, launched a revolution; one that sent out shockwaves that can still be felt today. It is the first DNA fingerprint, taken on a Monday morning at the University of Leicester by Alec Jeffreys, now Sir Alec in recognition of his momentous achievement.

The fuzzy pattern that he recorded on an X-ray film was based on genetic material from one of his technicians, Vicky Wilson. At that time, Sir Alec was investigating highly repetitive zones of the human genetic code called “minisatellites”, where there is much variation from person to person. He wanted to study these hotspots of genetic change to find the cause of the DNA diversity that makes every human being on the planet unique.

Gazing at the X-ray film recording Wilson’s minisatellites, he thought to himself: “That’s a mess.” But then, as he told me, “the penny dropped”. In this mess he stumbled on a kind of fingerprint, one which showed not only which parts of Wilson’s DNA came from her mother and which from her father, but also the unique genetic code that she possessed, one that was shared by no other human being on the planet.

In that Eureka moment, the science of DNA fingerprinting was born.

Sir Alec and his technician made a list of all the possible applications of genetic fingerprinting – but it was his wife, Sue, who spotted the potential for resolving immigration disputes, which in fact proved to be the first application.

Soon after his discovery, Sir Alec was asked to help confirm the identity of a boy whose family was originally from Ghana. DNA results proved that the boy was indeed a close relation of people already in the UK. The results were so conclusive that the Home Office, after being briefed by the professor, agreed to drop the case and the boy was allowed to stay in the country, to his mother’s immense relief. “Of all the cases,” he recalls, “this is the one that means most to me.’’

Sir Alec is the first to admit that he never realised just how useful his work would turn out to be: in resolving paternity issues, for example, in studies of wildlife populations and, of course, in many criminal investigations (DNA fingerprinting was first used by police to identify the rapist and killer of two teenage girls murdered in Narborough, Leicestershire, in 1983 and in 1986 respectively).

Similar methods were used to establish the identity of the ‘Angel of Death’ Josef Mengele (using bone from the Nazi doctor’s exhumed skeleton), and to identify the remains of Tsar Nicholas II and his family – in the course of which the Duke of Edinburgh gave a blood sample.

Sir Alec told the University recently: “The discovery of DNA fingerprinting was a glorious accident. It was best summarised in a school project that a grandson of mine did years ago: ‘DNA fingerprinting was discovered by my granddad when he was messing about in the lab’. Actually, you can’t describe it better than that – that is exactly what we were doing.”

Sir Alec has long been concerned about the world’s DNA databases. He describes how there needs to be a balance between the state’s rights to investigate and solve crime and an individual’s right to genetic privacy. “I take the very simple view that my genome is my own and nobody may access it unless with my permission.”

As for what happens next, Sir Alec says: ‘I’m now retired and consequently busier than ever.’