Dr Helen Peavitt, curator of Consumer Technology, explores the technology used to climb Mount Everest.

At 11.30am, on this day (29 May) in 1953, Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first people in the world to reach the summit of Mount Everest. They were part of the expedition team led by John Hunt. Despite the relative ‘ease’ with which the summit is climbed today by increasing numbers of people, the magnitude of the 1953 achievement cannot be underestimated. The mountain still maintains its mystique and reasserts its perilous nature during each climbing season, with an average of one death for every ten successful attempts on the summit.

The infamous character of the Himalayan peak began in 1852, when George Everest’s Great Trigonometrical Survey of India established peak ‘b’ as the survey team first called it as the highest mountain in the world. Straddling Nepal and Tibet – both secretive, inaccessible countries at the time – it was perhaps inevitable that it would enter the imagination of many by providing another unknown, uncharted territory to explore. After the Tibetan government opened up the country to the British in the 1920s, attempts on the mountain’s summit from the north side by a rash of British-led teams began. The successful 1953 party scaled the mountain from the south side.

The Science Museum holds a number of artefacts from some of the more well-known attempts on the summit. These reveal both the very private and the public nature of climbing the mountain. Hilary himself commented:

‘Nobody climbs mountains for scientific reasons. Science is used to raise money for the expeditions, but you really climb for the hell of it’

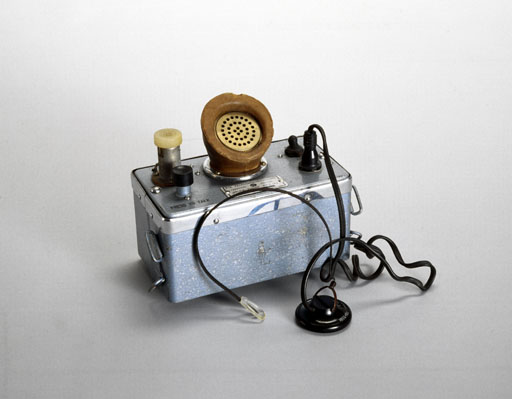

However, much of the equipment developed for the 1953 expedition used cutting-edge technology. For example, the Pye wireless equipment used, including the walkie talkie in the image below, was specially adapted by Pye for the extremes of weather and temperature experienced on the mountain. This enabled the team to receive broadcasts from the world outside and to communicate with camps up to two miles away.

An oxygen cylinder from the British 1922 Everest Expedition, shows how even the air we take for granted has to be supplied for most climbing teams at such high altitude. The oxygen levels above 8,000m in the mountain’s Death Zone, are so low that the body uses its store of oxygen up faster than it can be replenished by breathing.

Many of the other Everest-related objects in our collections are more personal items of clothing. There are butter-soft silk gloves and a pair of special lightweight double clinker nailed climbing boots from the 1933 expedition; and a fibre jacket from a 1978 climb – the first successful ascent without bottled oxygen.

Whilst these objects are all in the Museum’s stores, a lurid waterproof jacket and trousers by Karrimor, using Gore-Tex was worn by Rebecca Stephens, the first British woman to climb Everest on the 40th Anniversary Expedition in 1993; is on show in the Challenge of Materials gallery.

There’s also a pair of Indian puttees belonging to Dr Tom Longstaff from the 1922 expedition – the first which set off with the expressed purpose of reaching the summit. Longstaff advised against the expedition’s third attempt on the summit during which seven were killed by an avalanche. Many of these objects form poignant and intimate reminders of the very personal nature of climbing the most famous mountain in the world.