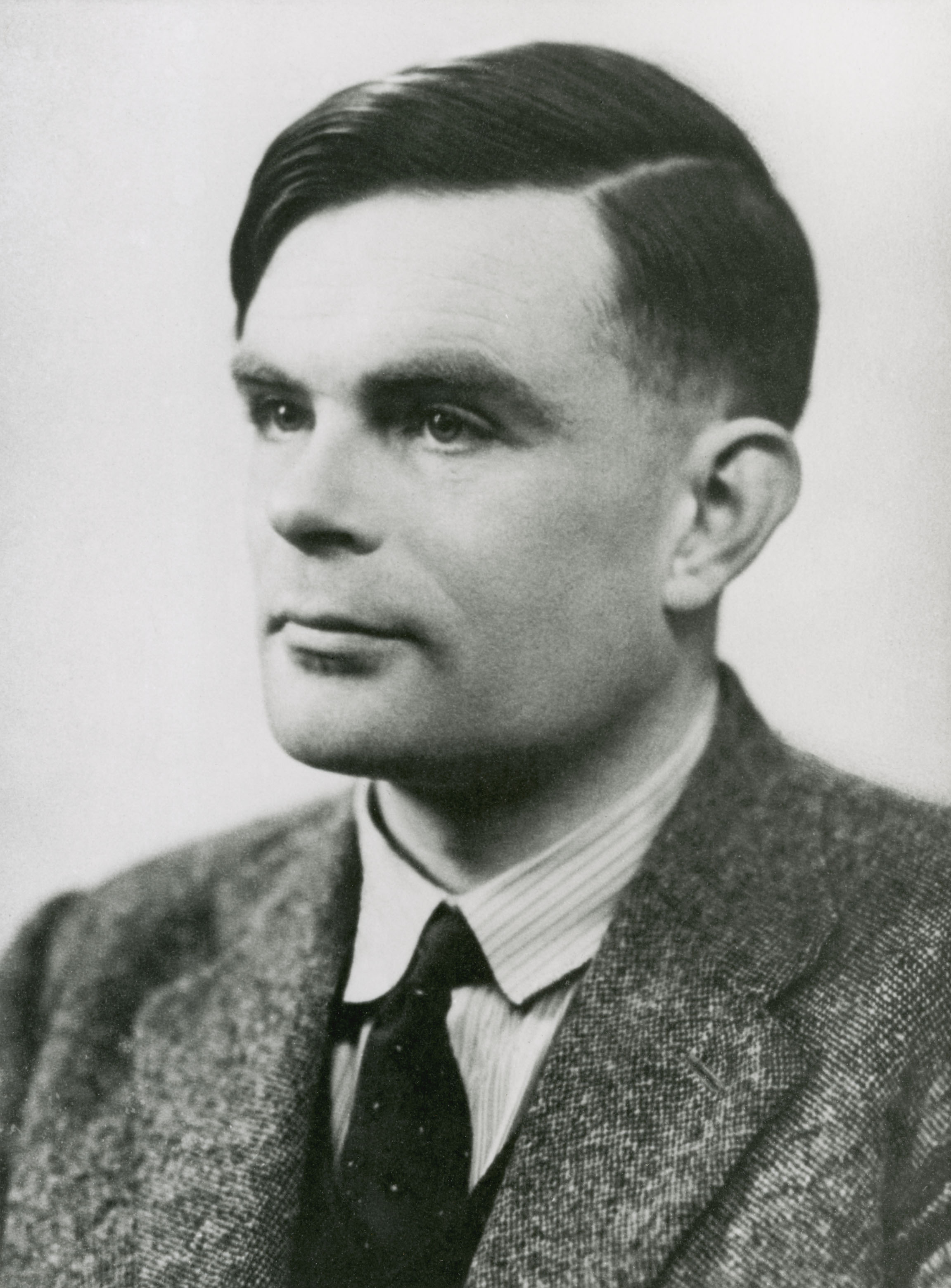

Alan Turing, the wartime codebreaker who laid the mathematical foundations of the modern computer, has been granted a posthumous pardon by the Queen for his criminal conviction for homosexuality.

A Royal pardon is usually only granted where a person has been found innocent of an offence and a request has been made by a family member. This unusual move brings to a close a tragic chapter that began in February 1952 when Turing was arrested for having a sexual relationship with a man, then tried and convicted of “gross indecency”.

To avoid prison, Turing accepted treatment with the female sex hormone oestrogen: ‘chemical castration’ that was intended to neutralise his libido.

Details of the circumstances leading to his death on 7 June 1954, at home in Wilmslow, Cheshire, can never be known. But Turing had himself spoken of suicide and this was the conclusion of the coroner, following an inquest.

In 2009 Gordon Brown, the then Prime Minister, issued a public apology for his treatment. A letter published a year ago in the Daily Telegraph, written by Lord Grade of Yarmouth and signed by two other Science Museum Trustees, Lord Faulkner of Worcester and Dr Douglas Gurr, called on the Prime Minister to posthumously pardon Turing.

Turing has now been granted a pardon under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy after a campaign supported by tens of thousands of people. An e-petition calling for a pardon received more than 37,000 signatures.

Chris Grayling, the Justice Secretary, said: “A pardon from the Queen is a fitting tribute to an exceptional man.”

The pardon states: “Now know ye that we, in consideration of circumstances humbly represented to us, are graciously pleased to grant our grace and mercy unto the said Alan Mathison Turing and grant him our free pardon posthumously in respect of the said convictions.”

But the reaction to the news has been mixed. Turing biographer Dr Andrew Hodges, of Wadham College, Oxford, told the Guardian newspaper : “Alan Turing suffered appalling treatment 60 years ago and there has been a very well intended and deeply felt campaign to remedy it in some way. Unfortunately, I cannot feel that such a ‘pardon’ embodies any good legal principle. If anything, it suggests that a sufficiently valuable individual should be above the law which applies to everyone else.

“It’s far more important that in the 30 years since I brought the story to public attention, LGBT rights movements have succeeded with a complete change in the law – for all. So, for me, this symbolic action adds nothing.

“A more substantial action would be the release of files on Turing’s secret work for GCHQ in the cold war. Loss of security clearance, state distrust and surveillance may have been crucial factors in the two years leading up to his death in 1954.”

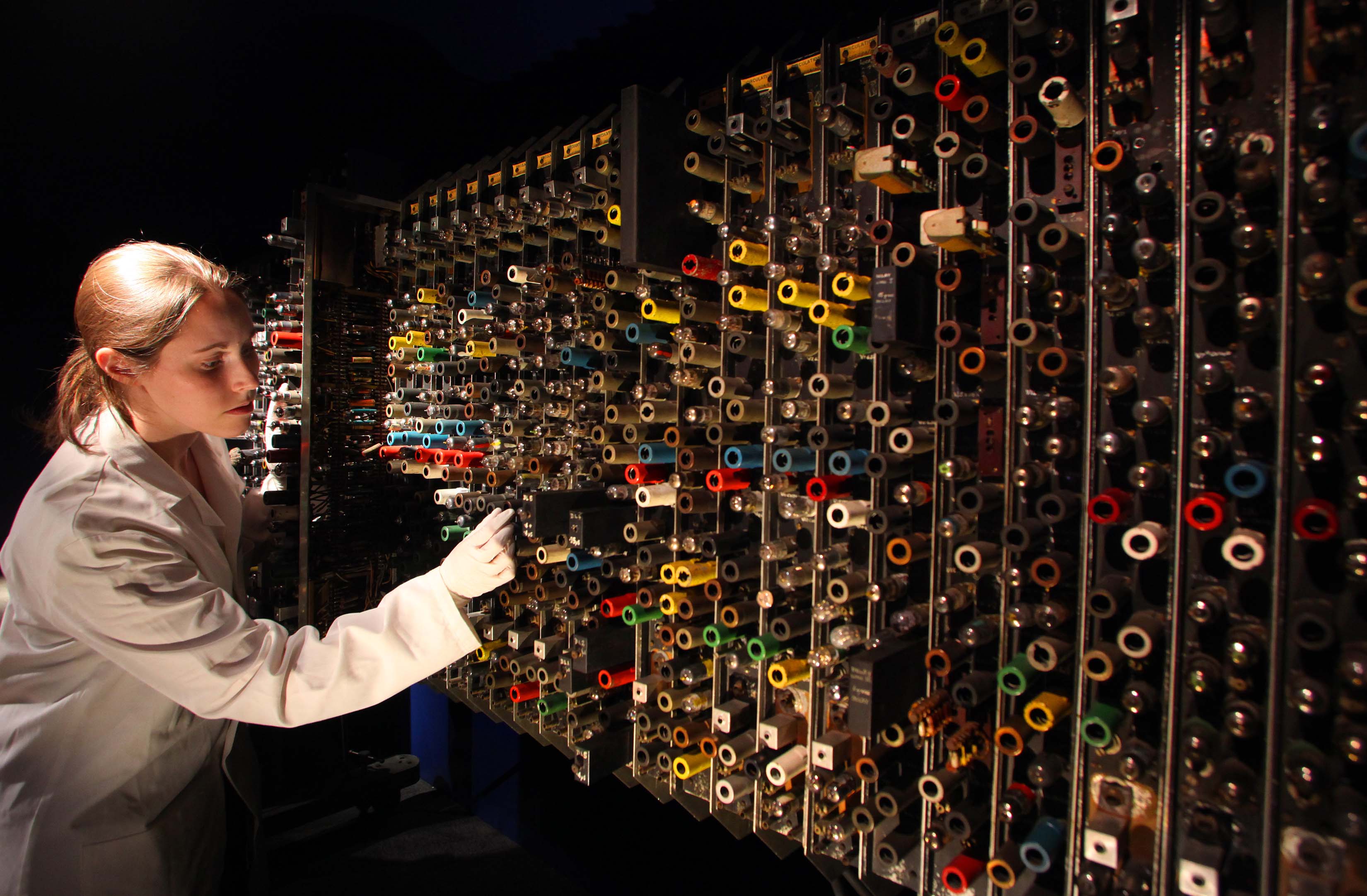

The Science Museum’s award-winning Turing exhibition,which closed a few months ago, showed that a signature moment of Turing’s life came on February 13, 1930, with the death of his classmate and first love, Christopher Morcom, from tuberculosis.

As he struggled to make sense of his loss, Turing began a lifelong quest to understand the nature of the human mind and whether Christopher’s was part of his dead body or somehow lived on.

Earlier this year Turing’s Universal Machine, the theoretical basis for all modern computing, won a public vote, organised by the Science Museum, GREAT campaign and other leading bodies in science and engineering to nominate the greatest British innovation of the last century.