This is undoubtedly our most famous painting: Philip J. de Loutherbourg’s 1801 ‘Coalbrookdale by Night’, a noisome depiction of the industrial revolution in all its terrible glory.

Here are the ‘Bedlam furnaces’ in action – open coke hearths used for smelting iron, the visible face of a burgeoning coal industry. But if we dig a little deeper, we find a rich and little-known iconographic seam in the Science Museum’s art collection.

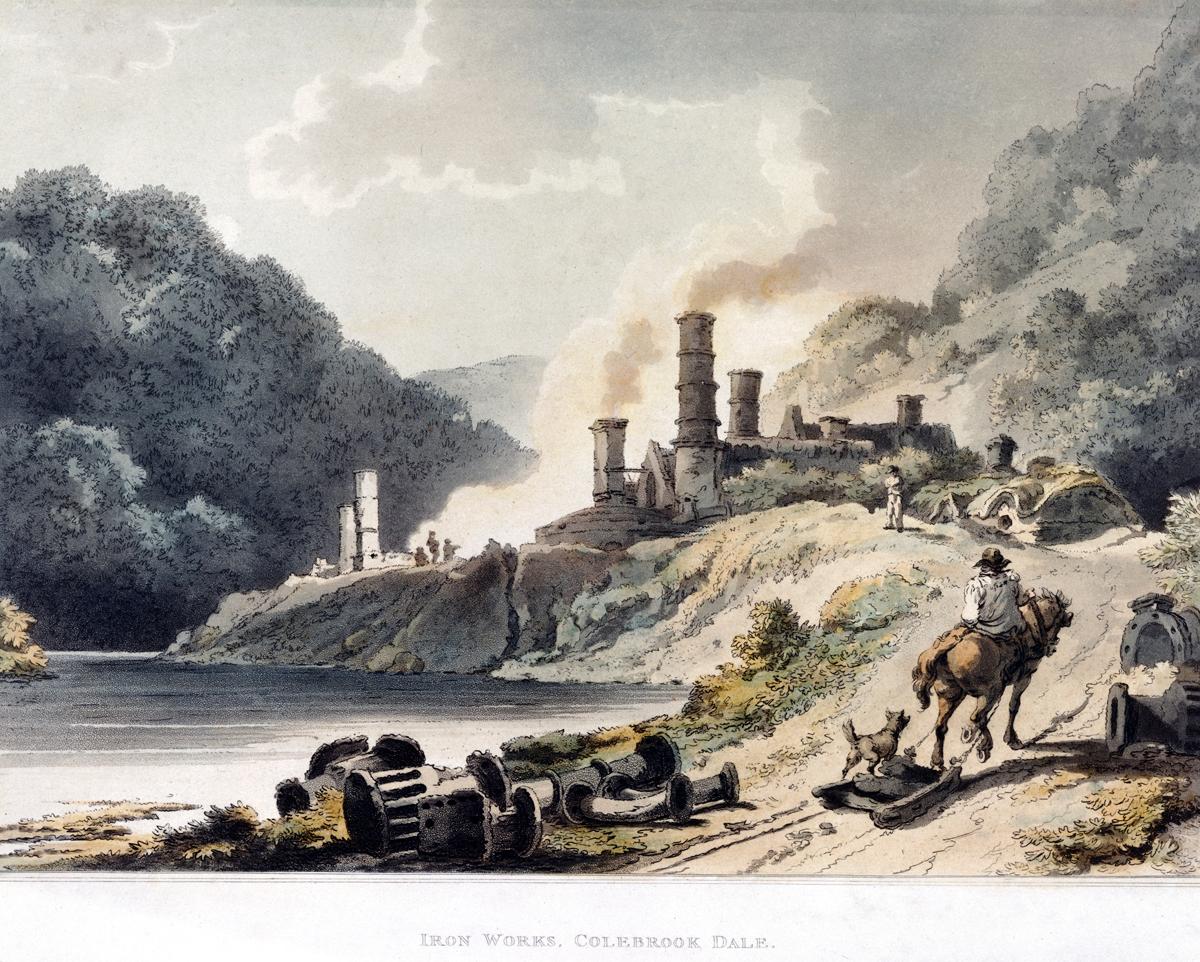

For one thing, what de Loutherbourg saw at Coalbrookdale was not all fire and brimstone:

In this engraving, done only a few years after ‘Coalbrookdale’, everything is reversed: night has become day, the horse returns, and the sublime power of the iron works has transformed into picturesque calm. This is in line with much 19th-century industrial art; in the 1840s, for example, W. Wheldon produced the following two oil-paintings of collieries:

Although he shows us the pollution at one colliery and the rough incursion into the landscape of the other, Wheldon’s pit-heads and coke ovens are undoubtedly clean and well organised, the elegant buildings perhaps even preferable to unruly Nature.

Attractive as these images are they don’t really tell us what life was like in the heart of the colliery, deep underground in the mines themselves. Such frank portrayals of the lives of miners are rare – it’s not easy to get access to a mine, much less to publicise its cruel machinations.

But amongst the Science Museum’s pictorial collections there is one such piece of documentary evidence: a remarkable set of amateur paintings, dating from the 1920s and ’30s, done by a miner called Gilbert Daykin. After each day at the pit Daykin would return home to paint from memory in his kitchen studio. Here is his 1934 ‘Thirst – The End of a Shift’, in which the deputy looks on dispassionately as one of his charges drinks from his 3-pint ‘Dudley’ flask:

In all of his works Daykin shows the stoic miners, neither pitying nor lionizing them. Yet he was subtly polemical. Another 1934 painting is entitled ‘The Tub: At the end of the coalface’, and shows two men working in cramped conditions:

The startling light and looming shadows create an impressive scene, an apt counterpart to de Loutherbourg’s grandiose ‘Coalbrookdale by Night’. But look closely and you’ll see that all is not well: the main crossbeam is cracking. The miner, his head touching the ceiling, is at risk of being crushed.

As Daykin said when interviewed for his exhibition: “I live in eternal dread of some injury to my eyes and hands. I am a specialist in dangerous jobs.” In 1939 Daykin was killed when the mineshaft he was working in collapsed.