When Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft made its delicate touch-and-go landing on the surface of asteroid Ryugu in 2019, it scooped up more than just dust. The return capsule, which parachuted down into the Australian outback a year later, carried fragments of the early solar system: pristine samples of a carbonaceous asteroid, a type rich in carbon and water. One of these grains was recently on display in the Science Museum, a remarkable souvenir of a rock that once orbited between Mars and Jupiter.

What these flecks of asteroid have revealed is a story that stretches across billions of years. According to a study published today in Nature by Tsuyoshi Iizuka of the University of Tokyo and colleagues, Ryugu’s parent body did not simply undergo a brief watery adolescence soon after its birth. Instead, fluids trickled through the rock more than a billion years after it formed—long after planetary scientists thought such asteroids had dried out.

The result complicates, and potentially enriches, one of the most profound stories in planetary science: how Earth and its neighbours acquired their water. As ever in science, however, the new finding raises as many questions as it answers, agreed Dr Iizuka.

Rocks with Long Memories

Carbonaceous asteroids are the most common residents of the outer asteroid belt, relics of the primordial solar system. They are built from dust and ice that condensed in the frigid outskirts of the Sun’s disk some 4.5 billion years ago. These bodies are time capsules: unmodified pieces of the protoplanetary soup that coalesced into planets. For decades, scientists have wondered whether such asteroids were couriers, delivering both water and organic molecules to the infant Earth, potentially setting the stage for life.

The prevailing picture has been one of early, short-lived fluid activity. Radioactive isotopes such as aluminium-26, abundant in the solar system’s youth, would have provided enough heat to melt internal ice. That liquid water could percolate through the porous rock, altering minerals before freezing again within a few million years. But once the short-lived isotopes decayed, the heat source vanished, and the story was thought to have ended.

Not so, according to the new isotopic studies of Dr Iizuka’s team.

Lutetium, hafnium and a cosmic stopwatch

The researchers turned to the decay of lutetium-176 into hafnium-176, which can be used as a kind of clock, an isotopic dating method, to work out the age of ancient rocks. In Ryugu’s case, the technique was adapted to track the movement of elements carried by late-moving fluids. The team found an unexpected excess of hafnium-176—chemical fingerprints of lutetium atoms having been dissolved, transported and redeposited by liquid more than a billion years after Ryugu’s parent body had formed.

When the team saw the excess, their first reaction was that they had made a mistake, Dr Iizuka said. But given they processed half a dozen different meteorite samples, they were convinced: ‘the results of Ryugu are real.”

What could have rekindled this late flow? The authors of the Nature paper suspect a collision. An impact would have generated heat, melted buried ice, and opened fractures. For a brief geological moment, water was once again on the move.

This finding doubles or triples the likely water inventory of such asteroids, at least in principle. If they could sustain multiple episodes of flows, they may have ferried more water to the terrestrial planets than previously estimated. In other words, delivery of water-bearing material to Earth could have occurred not just during the planet’s violent youth but throughout its more sedate middle age: Earth’s oceans may have arrived in trickles over eons rather than in one deluge if carbonaceous meteorites landed on our home world over a billion-year timescale.

That widens the window for planetary habitability, both in our solar system and elsewhere.

From Dust to Display

This scientific story is far from over. The samples remain under scrutiny by laboratories worldwide. There are plans to compare them with Bennu, another carbonaceous asteroid sampled by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission. ‘We would like to analyse Bennu samples to check if the Ryugu case is common or not,’ said Dr Iizuka. The aim is not just to reconstruct Ryugu’s biography but to understand the larger family of asteroids—and, ultimately, to piece together the history of Earth itself.

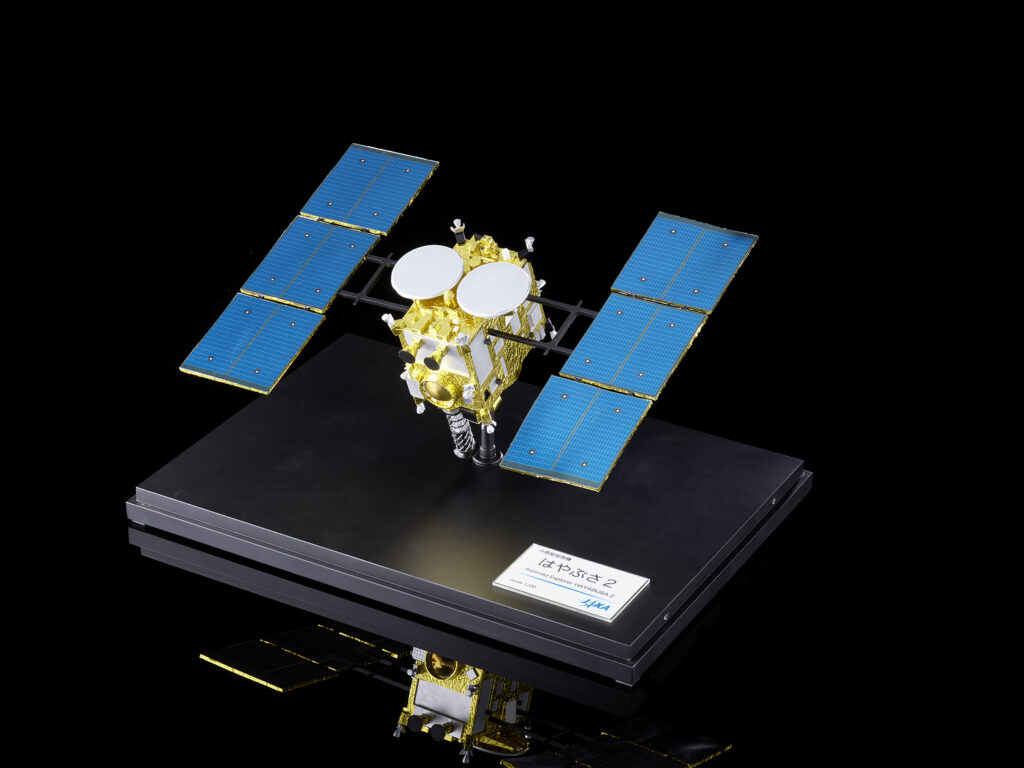

Back on Earth, the Ryugu samples—each no bigger than a breadcrumb—have become objects of fascination. When the Science Museum recently displayed one of the returned grains, it was a public testament to international collaboration and technical derring-do, along with a reminder that our planet’s life-giving oceans had cosmic origins.