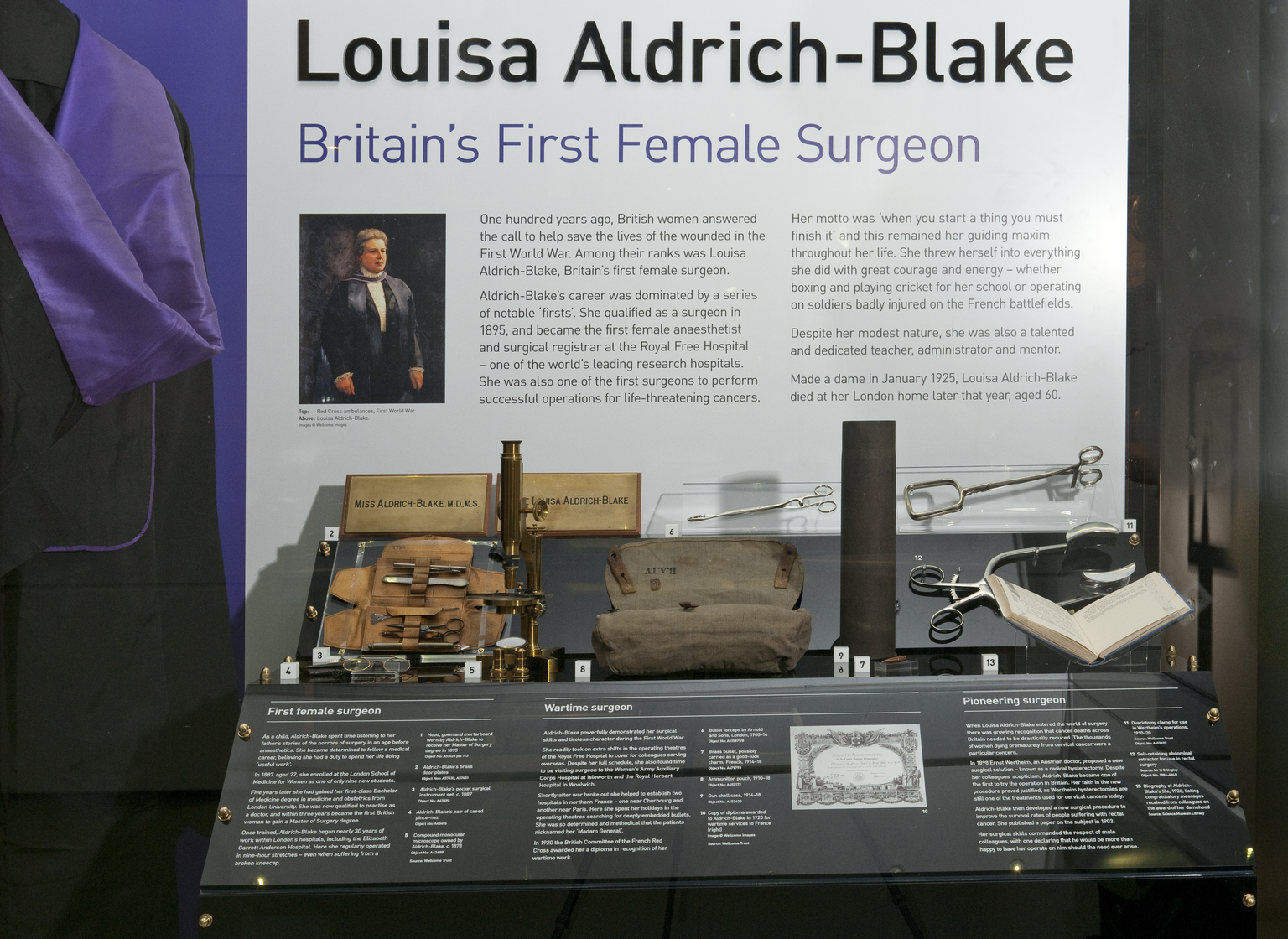

The medical achievements of Dame Louisa Aldrich-Blake (15 August 1865 – 28 December 1925), Britain’s first female surgeon, came under the spotlight in a 2015 display at the Science Museum.

If her name isn’t familiar then it certainly deserves to be. A century ago Dame Aldrich-Blake was busy writing to every woman on the medical register to enlist their help in setting up hospitals to treat soldiers injured on the eastern battlefields of the First World War.

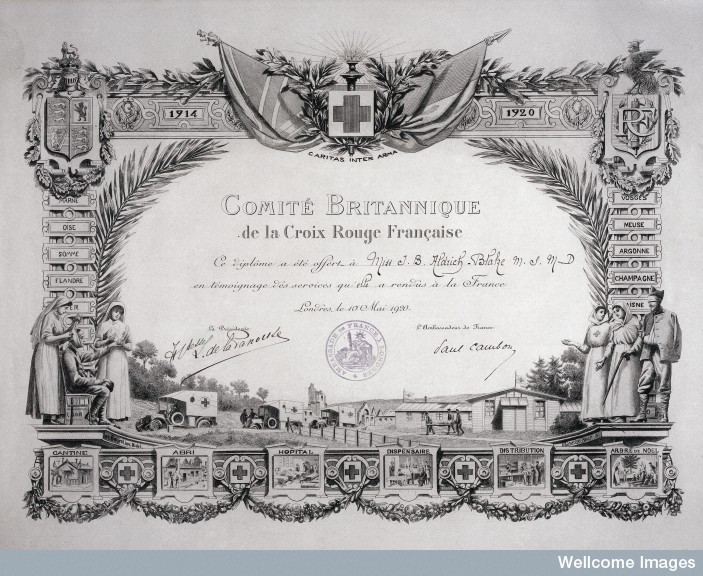

Aldrich-Blake’s war work saw her, temporarily, leave the shores of Britain. In 1915 she crossed the Channel to work as surgeon for the Anglo-French Red Cross in the 600-bed field hospital at Abbaye du Royaumont near Paris. Conditions there were certainly very difficult. Louisa characteristically rose to the challenge, seeking out every trace of bullet fragments from the war-torn bodies of those under her knife. Such determination earned her the nickname of ‘Madame Générale’ from her patients.

Image © Wellcome Images, London.

The work of Louisa and her fellow female doctors serving overseas helped turn the tide of popular opinion back home in their favour. Their skill and dedication in treating soldiers, often close to the front line, was widely recognised and welcomed – helping to silence the War Office, which was initially reluctant to enlist the help of female medical staff. Furthermore, their example inspired other women to enter medical school for the first time.

By the time war broke out Louisa’s own medical career was already distinguished. She enrolled at the London School of Medicine for Women in 1887 aged 22, along with a handful of other new students. Her ambition was largely driven by a deeply held desire to do ‘something useful’. After completing her bachelor degree in medicine she quickly gained her Master of Surgery degree – the first British woman to do so. She also became Dean of the London School of Medicine for Women.

Aldrich-Blake also researched and pioneered new surgical methods to treat cervical and rectal cancers. In 1903 her paper on a new procedure to treat rectal cancer was published in the British Medical Journal. She was evidently extremely proud of this, because if you leaf through her notebooks – now held at the Wellcome Library in London – you will find a copy of the paper, carefully folded and pressed between the pages.

Aldrich-Blake’s contribution to medicine is celebrated in a statue erected in her honour in Tavistock Square in London – near the headquarters of the British Medical Association.

Dame Louisa Aldrich-Blake’s life and work was celebrated in a 2015 display at the Science Museum.