On this day (3 November) in 1957, just one month after the launch of Sputnik, a dog called Laika became the first living creature to orbit the Earth. But sadly, with no means of returning her safely to Earth, she was on a one-way mission. Enough reserve supplies were prepared for Laika to survive one week in orbit inside the Sputnik 2 satellite, but she overheated and died only a few hours after launch.

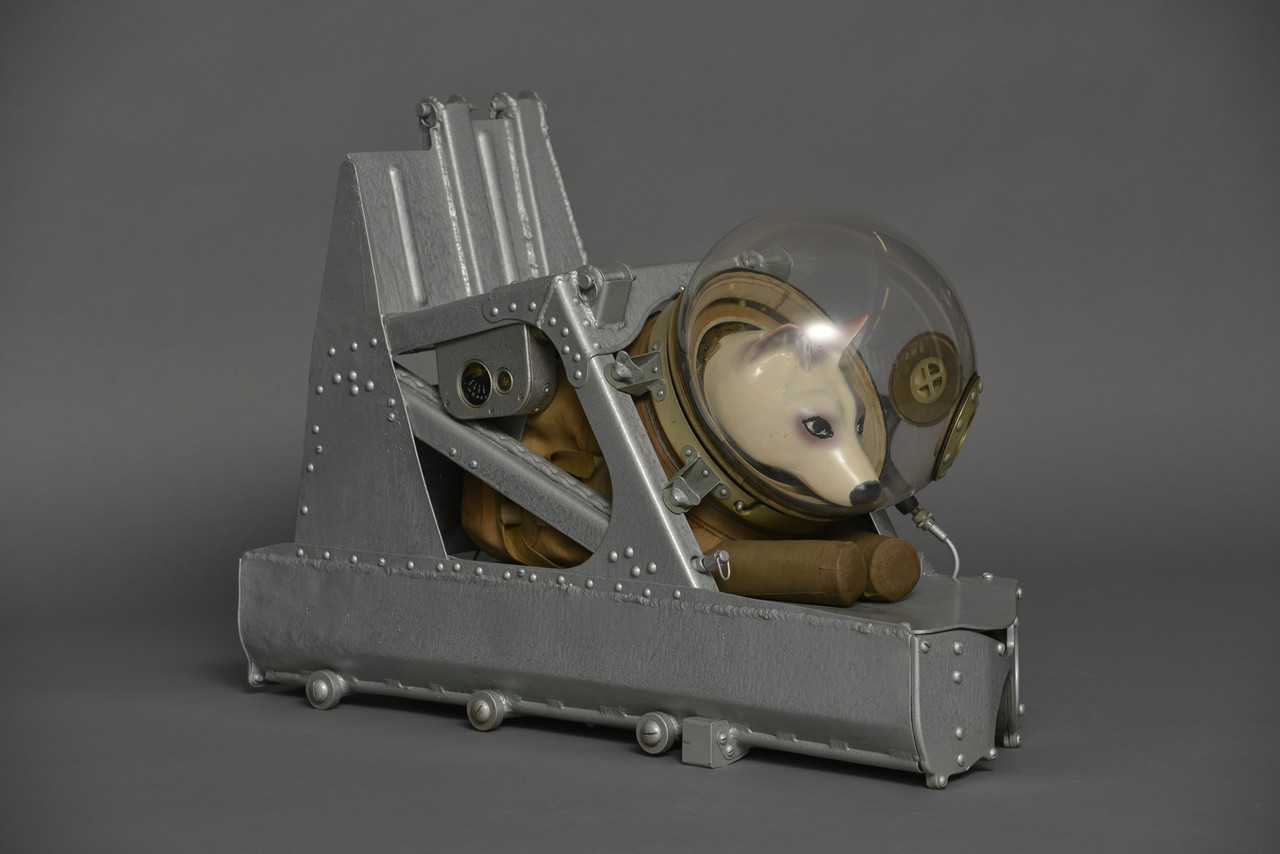

Laika’s flight followed earlier stratospheric flights with dogs as crew. These sub-orbital missions were crucial for gathering knowledge of what happens to living creatures in space, as well as testing the equipment, ejection and parachute landing systems that would later be used by cosmonauts. The space dogs were used all the way up until the first manned space flight and after, flying in Vostok-type spacecraft.

On 22 July 1951, after six months of training, two small dogs nicknamed Tsygan and Dezik were launched from the site of the first Soviet cosmodrome in a region called Kapustin Yar. At a height of 110 km, the head of the rocket containing the dogs separated and began to free-fall back down to Earth. They experienced intense G-forces during descent, but after a heavy jolt from the parachute, the cabin containing the two four-legged pilots slowed and touched down safely. The trip, which lasted 15 minutes from start to finish, made Tsygan and Dezik the first animals to experience space flight and to emerge from the craft unharmed.

The completely new field of space biology was asking many questions about whether humans and other animals could survive an extended trip into outer space. The scientists involved needed to test the boundaries of endurance on actual living creatures. Was it possible to survive the extreme accelerations and decelerations of launching and landing? How could basic life-support needs – such as air, water and food – be supplied away from the home planet? And finally, would the experience of weightlessness inside a small capsule be harmful? Scientists needed to test life-support equipment, develop a training regimen for crews and perform tests in space. All of this had to be completed before human crews could embark on space exploration.

By the time of the first Soviet space dog crew, American scientists had attempted a number of launches using monkeys in V2 and Aerobee rockets, and all of them ended in the death of the animals. But the information collected during the flights demonstrated that the animals could cope with the intense G-forces and stresses of the rocket launches.

Chief Designer Sergei Korolev decided that the Soviet space programme would, on the other hand, work with dogs. The choice of dogs, ‘man’s best friend’, over monkeys, among our closest genetic relatives, was based on rational reasoning springing from emotional attachment. The Russian scientists believed they could build stronger bonds with the animals and so ensure their obedience. They also believed that the dogs eking out an existence on the harsh streets of Moscow would possess a survivalist temperament.

There were strict criteria for scouting the first-star squad of dogs. They had to be female because the specialised clothing and toilet technology was easier to tailor to them. And they needed to be small in size: 6 to 7 kg each to accommodate the strict weight limit for the rocket. These dogs also needed to have light-coloured fur, in order to show up clearly in front of the onboard camera. The scientists had even attempted to bleach the fur of one of their favourite darker dogs without success.

In the six years of stratospheric dog flights only a few launches ended in tragedy. But through these sacrifices, enough information was gathered on whether living beings were likely to survive a trip into space. After the launch of an untrained puppy called ZIB (a quick replacement for a runaway dog), Chief Designer Korolev was ecstatic. At the landing site, when greeted by the happy puppy, he announced to his colleagues:

‘Space travellers will soon be flying in our spaceships with state visas – on a holiday!’

These early tests, conducted in secrecy, culminated in the final question: could a living creature survive a prolonged stay in zero gravity?

The most successful canine mission was perhaps the one performed by Belka and Strelka in 1960, who completed 18 orbits and returned to Earth in perfect health. They were greeted by an international press corps at a news conference in Moscow and their friendly faces were broadcast around the world. Belka went on to have a litter of puppies, one of which was given to the American first lady Jacqueline Kennedy by Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev.

At the time of this gift, Korolev already knew the name of the cosmonaut who would be the first to fly into space. By the time of Gagarin’s flight, 48 dogs had been to space and 20 had perished.