Christopher Nolan’s latest block-buster Dunkirk depicts the Battle of Dunkirk which took place during World War II. As France fell and the German army advanced on Allied forces, Dunkirk became the focal point for what would become one of the greatest evacuations in military history. Code-named ‘Operation Dynamo’, more than 330,000 British, French, Belgian and Polish troops were rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk between 26 May and 3 June 1940.

At the Science Museum you can watch Dunkirk on one of the largest IMAX screens in the UK (on 70mm IMAX film) and also see a real Royal Air Force Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane (which fought over Dunkirk and in the Battle of Britain) in our Flight Gallery.

Contrary to common knowledge of the events at Dunkirk, the RAF made a significant contribution to the evacuation of Allied forces. Although soldiers on the beach believed they had been abandoned as they could not see Allied aircraft, the RAF were fighting the Luftwaffe (German air force) over the English Channel.

In May 1940, the RAF faced its first true test against an experienced Luftwaffe. Tasked with protecting the evacuating troops during Operation Dynamo, the RAF targeted the advancing German army and fought Ju 87 Stukas, Messerschmitt 109s and Heinkel 111s high in the sky. As well as an original Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, you can also view scale models of the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the Ju 87 Stuka in our Flight Gallery.

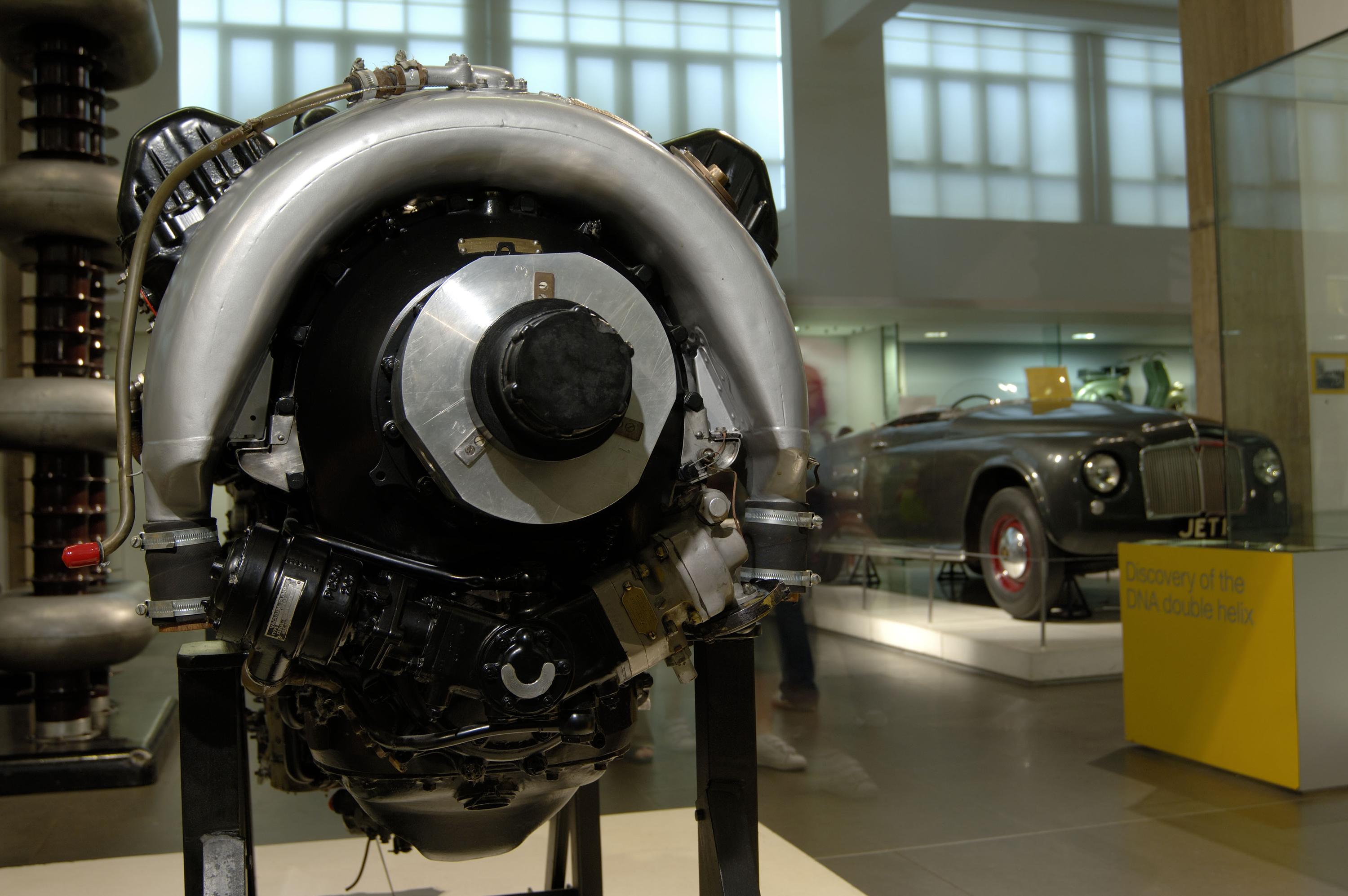

A British legend, the Supermarine Mk1 Spitfire was integral to Britain’s front-line air defence during World War II. Together with the Hawker Hurricane, both aircraft played a key role in Operation Dynamo and the Battle of Britain in 1940. Powered by the new Rolls-Royce Merlin engine (on display in our Making the Modern World Gallery) the Spitfire and Hurricane along with the Royal Navy, provided enough cover at Dunkirk to allow the Allied troops time to evacuate the beach.

As depicted in the film, the amount of fuel each RAF aircraft could carry severely limited their flight time. Once the pilot made it across the English Channel, there was only enough fuel for one hour of fighting over Dunkirk before the pilot had to return to Britain to refuel. Often, Spitfires and Hurricanes met the Luftwaffe on route to Dunkirk as bombers targeted Royal Navy ships and destroyers. Pilots were forced to battle the Germans over the sea, leaving the aircraft with little or no fuel left to continue onto France.

The Hawker Hurricane on display in the Science Museum’s Flight Gallery fought over Dunkirk and in the Battle of Britain.

It was piloted by P.O. Anthony Woods-Scawen of 43 Squadron from Tangmere and took part in the defensive patrol over Dunkirk beaches. It attacked and damaged two Me 109s, but was hit and forced to land back in Tangmere. After some repairs, it relocated to the No 615 ‘County of Surrey’ Squadron. Piloted by P.O. David Looker, it was attacked by a Bf 109 and crash-landed on fire at Croydon aerodrome in August 1940.

The Hurricane was slower than the Spitfire, but was a much sturdier machine, able to withstand heavier battle-damage. It could be maintained and repaired more easily than the Spitfire. The Hurricane made up more than 60 percent of RAF fighter strength during the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. Due to its slower speed, Hurricanes usually attacked opposing bombers, such as Heinkel 111s and Ju 87 Stukas, while Spitfires went after the bomber escorts like Messerschmitt Bf/Me 109s, which were much quicker. The Hurricane accounted for the greatest number of enemy aircraft destroyed in the Battle of Britain.

Many who fought and were evacuated at Dunkirk never saw the RAF in amongst the terrifying dive-bombing Stukas or the Heinkel 111s as they dropped bomb after bomb on Royal Navy ships and soldiers stranded on the beach. In reality, the Spitfire and Hurricane were critical components in the successful Allied evacuation.