The grand salons of 18th-century Paris and Versailles were hugely influential cultural hubs, when Enlightenment thinkers played word games, gossiped, and came to ponder the cosmos, humanity, and the laws governing both, buoyed by the revolutionary ideas of thinkers such as Isaac Newton (1643-1727).

Among the throng was one of the stars of our latest exhibition, Versailles: Science and Splendour. Émilie Du Châtelet (1706-49) – noblewoman, mathematician, and natural philosopher – played one of the most critical roles in disseminating Newton’s work, particularly his Principia Mathematica. This was his great treatise on gravity and mechanics that, at a stroke, united the terrestrial movement of cannonballs with the motions of the planets and other objects in the heavens.

It is remarkable that Du Châtelet took on the job at all, given the 18th-century French intellectual landscape was unreceptive to both women and Newton. Cartesianism, developed by the French mathematician and scholar René Descartes (1596–1650), still dominated French scientific thought.

‘The French accepted Newton’s ideas about gravitation on Earth but they balked at his hypothesis that this same gravity governed the universe,’ comments Judith P. Zinsser, Du Châtelet’s biographer and Emerita Professor of Miami University. One reason was that the ‘Newtonian method’, the creative synergy between hypothesis and experiment still in use today, ignored causation. ‘Newton could offer no explanation for how universal gravitation worked,’ she adds.

Even the philosopher and writer Voltaire (1694-1778), one of Newton’s strongest supporters in France, acknowledged that Newton’s almost occult concept of gravity was tricky for his contemporaries to grasp. Enter Du Châtelet, both collaborator and romantic partner of Voltaire.

Du Châtelet began her monumental translation and commentary on the Principia in 1745, almost sixty years after it was first published and two decades after the death of Newton in 1727. This was no easy feat since ‘very few’ of her contemporaries in either Britain or France could understand the Principia, according to Patricia Fara, Emerita Fellow at the University of Cambridge and Versailles exhibition advisor.

Many intellectual women undertook translations during the Enlightenment period as the establishment deemed this an accepted scholarly activity for them. But, remarks Fara, it was unusual for a woman to translate from Latin and tackle such difficult mathematics. What is more, she also included commentaries that criticised Newton’s ideas and tried to reconcile them with those of other thinkers, notably Descartes.

Birth of a Luminary

Du Châtelet was born into an aristocratic family in 1706 as Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil. She benefitted from an unconventional father who encouraged what Zinsser says was ‘a boy’s education.’ By her early twenties, she was conversant with Italian and Latin and versed in mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy. She would come into her own after meeting Voltaire.

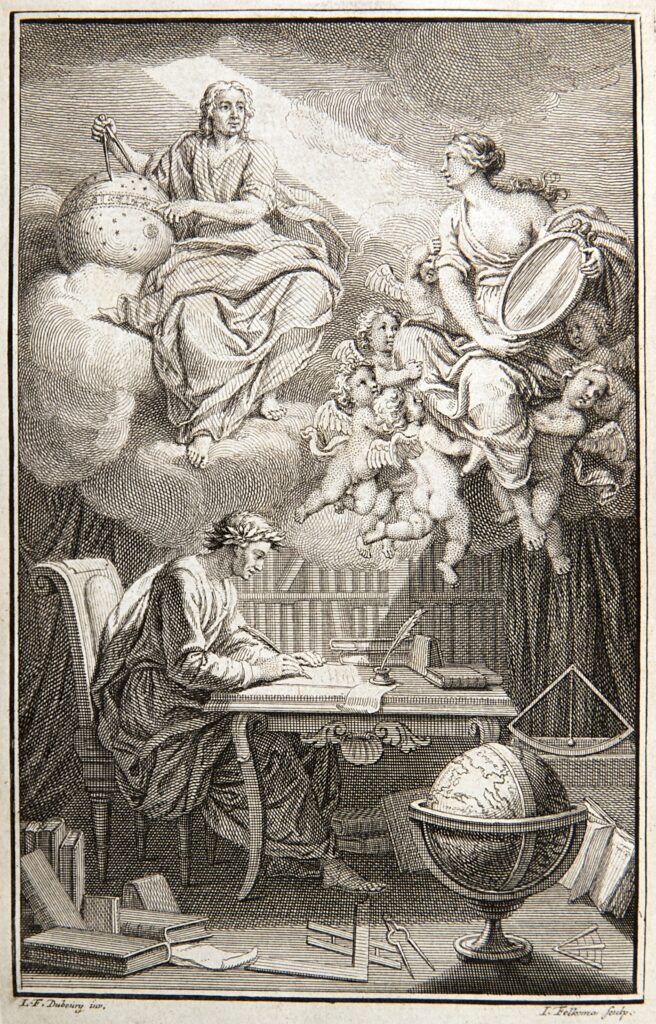

Voltaire himself was captivated by Newtonian mechanics, having witnessed their influence firsthand during his time in England. Together they wrote an introductory book, Elements of Newtonian Philosophy (1738), which persuaded French experimenters to abandon their national hero, Descartes. Although only Voltaire’s name adorns the title page, ‘their book’s frontispiece envisages Du Châtelet hovering above his head, casting Newton’s divine wisdom down onto his hand,’ says Fara. ‘Minerva dictated and I wrote,’ he told a friend.

Women in 18th-century Europe had few educational opportunities and were written off as intellectually inferior to men. By the time that she started to tackle Newton, explains Fara, Du Châtelet was married to a nobleman and military governor, the Marquis Du Châtelet, had given birth to three children, ‘and was simultaneously developing friendships with two other men.’

Tall, beautiful, and well dressed, with a penchant for dancing and gambling, she persuaded one of them to teach her mathematics and became besotted with the other, Voltaire, who once declared his lover ‘was a great man whose only fault was being a woman.’

As wife to the Marquis Du Châtelet, she became a member of the Queen’s entourage, an honour granted to only a few women of high status. When she made an embarrassing gaffe (she climbed into the first carriage to a royal hunting party, one deemed beyond her social position), an elderly nobleman who had served Louis XIV and now Louis XV, dismissed her faux pas, remarks Zinsser: ‘Madame Du Châtelet is distracted,’ – by implication, her mind was lost in science.

More than Voltaire’s mistress

Du Châtelet’s translation of the Principia Mathematica stands as an extraordinary intellectual feat, not least because the original Latin text was dense and mathematically challenging: Newton had deliberately made his Principia hard to understand to avoid being ‘baited by little Smatterers in Mathematick.’

Newton’s theories were unpacked by her with precision, annotating and explaining the principles behind his equations so that they were comprehensible to French Cartesian-trained minds. While Descartes envisioned the planets swirling within clouds of tiny invisible particles, says Fara, ‘Newton’s cosmos consisted largely of empty space, crisscrossed by invisible forces that obeyed a single mathematical law’.

Her commentary on the Principia also shows a remarkable degree of independence from Newton’s ideas, and chauvinism in general. As one example, Du Châtelet had to grapple with calculus — the mathematics of change and motion that Newton had pioneered, along with his German rival Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). As Fara comments, ‘Her contributions were significant because she commented on and criticised Newton’s ideas and included details of experiments and calculations that had been carried out since his death.’

Her work drew the admiration of European scholars. In fact, her translation, first published posthumously in 1756, with a final complete version in 1759, would remain the definitive French edition of the Principia for more than a century. In a sense, Du Châtelet’s work was also an early contribution to the concept of ‘popular science,’ bridging specialist knowledge and public discourse.

By rendering Newton’s work in French and painstakingly explaining its arguments and implications, she opened the door to Newtonian science, though her resulting impact was far from instantaneous. ‘Most French people continued to adhere to Descartes’s theories for several decades,’ comments Fara. ‘This was not just scientific recalcitrance and not straightforward chauvinism: they objected on religious/philosophical grounds to the idea that the power of gravity could be transmitted through empty space.’

The fall and rise of Du Châtelet’s reputation

Du Châtelet’s life was tragically brief — she died soon after her daughter was born in 1749, having worked up to 18 hours a day on the Principia, even plunging her hands into ice-cold water to keep herself awake. Du Châtelet was 42, an age which she knew only too well was particularly perilous for childbirth, having already lost one of her three previous children. However, she did manage to finish her magnum opus; on her last day, she recorded the date on her Newton commentary, remarks Fara.

Her friends safeguarded her manuscript, which remains the only complete version of the Principia in French, and, in tribute, published it the next decade, when Halley’s comet was predicted to return. The comet obliged late in 1758: another triumph for Newton’s physics.

‘Her translation, together with her two commentaries, an historical commentary and an analytical-mathematical commentary, brought about the breakthrough for Newtonian physics,’ comments Ruth Hagengruber of the University of Paderborn. ‘With her translation, she laid the foundations for the physics that was further developed.’

But in her lifetime and beyond, Du Châtelet was overshadowed by Voltaire. Denigration of Du Châtelet’s achievements would begin towards the end of the eighteenth century with the publication of her light-hearted memoir, the Discourse on Happiness, remarks Zinsser. ‘The final section where she considers the pros and cons of ‘love’, became the only idea biographers focused on. After the French Revolution she became the personification of the frivolous, licentious noblewoman.’ This image persisted for more than two and a half centuries. Nancy Mitford’s Voltaire in Love (1957) compared her book to ‘a Kinsey report’ on Du Châtelet’s and Voltaire’s ‘romps.’

Historians have increasingly recognised Du Châtelet as a formidable intellect, not only as Newton’s translator but as an original thinker who played a key role in advancing scientific thought. Du Châtelet’s image has been transformed as a result, says Zinsser, ‘Her works have been digitised, most now translated into English. She has had museum exhibitions, a French stamp and street named in her honour, and perhaps best of all, her birthday commemorated with a Google Doodle portraying her happily working on a manuscript amidst her mathematical and astronomical instruments.’

In Versailles: Science and Splendour, you can see Du Châtelet’s handwritten and annotated translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica under her portrait in which she works at her desk, dividers in hand. Her poised gaze reflects the sharp mind behind her extraordinary achievements.

Versailles: Science and Splendour is open at the Science Museum until 21 April. Tickets can be booked via our website or in person at the museum.