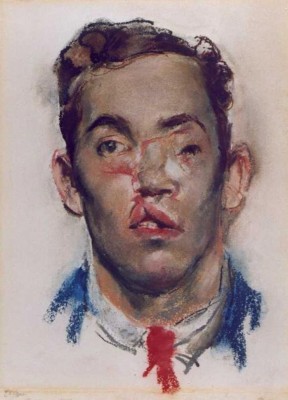

Of the many emotive objects found within our Wounded exhibition none have the power to move more than a series of pastel sketches that show the devastating facial injuries suffered by young Allied soldiers.

The drawings bear powerful testament to the dangers faced at the Western Front when heads placed above trench parapets were targeted by low-level gunfire and fast-moving shell fragments.

They also mark an important milestone in medical history, for they stand as early surgical records of the emerging discipline we now know as plastic surgery.

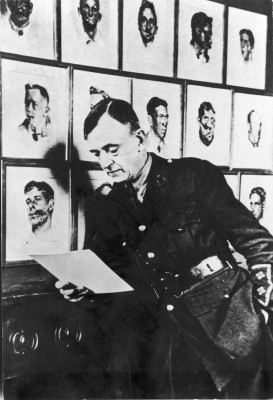

At the heart of the story was an ear, nose and throat surgeon from New Zealand by the name of Harold Gillies.

Having seen facial operations carried out in France – while serving with the Red Cross – Gillies led the call for similar treatment to be offered to soldiers returning to England.

He campaigned for the establishment of the world’s first dedicated hospital for facial injuries, which opened in a leafy suburb in northern Kent in August 1917.

This was known as the Queen’s hospital, Sidcup, and some 11,572 operations were carried out there before the unit closed in 1925.

As Gillies’ techniques were a new medical discipline much had to be learned through trial and error. His greatest accomplishment was the development of the tube pedicle skin-grafting technique.

In this technique the surgeon separated but did not detach a flap of skin from a healthy part of the soldier’s body, and took it across to the injured area, where it was sewn into place to allow new tissue to form.

Gillies’ colleagues also found a new way of administering anaesthetic to those suffering from facial injury by passing a tube into the windpipe through which ether could be fed directly into the lungs.

This technique remains the basis of anaesthesia today.

Gillies described plastic surgery as a ‘strange new art’ and saw illustration as a powerful tool with which to record surgical procedures and help the surgeon achieve an aesthetically pleasing result.

He worked alongside Henry Tonks, a surgeon turned painter and art teacher, who sketched the patients before, during and after their operations. Tonks left Sidcup in early 1918 to take up the role of official war artist in France.

Gillies also realised that 3D imaging could transform the work of the plastic surgeon. A team of sculptors were brought to Sidcup to make plaster casts of the men’s faces.

Artificial ears, noses and chins were added before surgery to show how a soldier’s face might look after the operation.

Kathleen Scott – widow of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott – was a talented member of the team. An example of a cast can also be seen in the Wounded exhibition.

The press heralded the work at Sidcup as ‘the most extraordinary medical discovery of the age’.

In reality, while great advances were made, many soldiers were left struggling to cope with the psychological impact of living with long-term disfigurement.

Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care opened at the Science Museum on 29 June 2016, and closed in June 2018. For more information visit sciencemuseum.org.uk/wounded.