Few could have imagined the impact of fertility science on society when Louise Brown, the first ‘test tube baby’, was born four decades ago, the Chair of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority told a recent conference in London, referring to the Science Museum’s recent exhibition.

Sally Cheshire, CBE, chair of the HFEA, said that the origins of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act still forms the basis of the framework by which the UK regulates patient treatment and human embryo research, even though its origins date back to 1990.

During the five months that the 40th anniversary of In Vitro Fertilisation was marked by the Science Museum, including a celebration of Louise Brown’s birthday, it is estimated that around 180,000 visitors saw the exhibition, IVF: 6 Million Babies Later.

Speaking at the Progress Educational Trust’s Annual Conference, held at Amnesty International in London, Sally Cheshire said: ‘The Science Museum exhibition I opened in July this year to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Louise Brown’s birth was called 6 Million Babies Later and, its estimated that by the end of this century, 400 million babies or 3% of the global population could exist by virtue of IVF babies and their descendants. We live in a world which the HFE Act could never have predicted.’

She acknowledged that advances such as mitochondrial donation, growing embryos for longer than ever before in the laboratory, artificial embryos, genome editing and more were pushing back the boundaries but was ‘not yet convinced’ that the HFE Act has to change, such as by modifying the rule that embryos should not be grown for more than 14 days in the lab, which rests on the work of Baroness Mary Warnock, who in 1984 led a committee which explored the borderlands that lie between acceptable and unacceptable research on the human embryo.

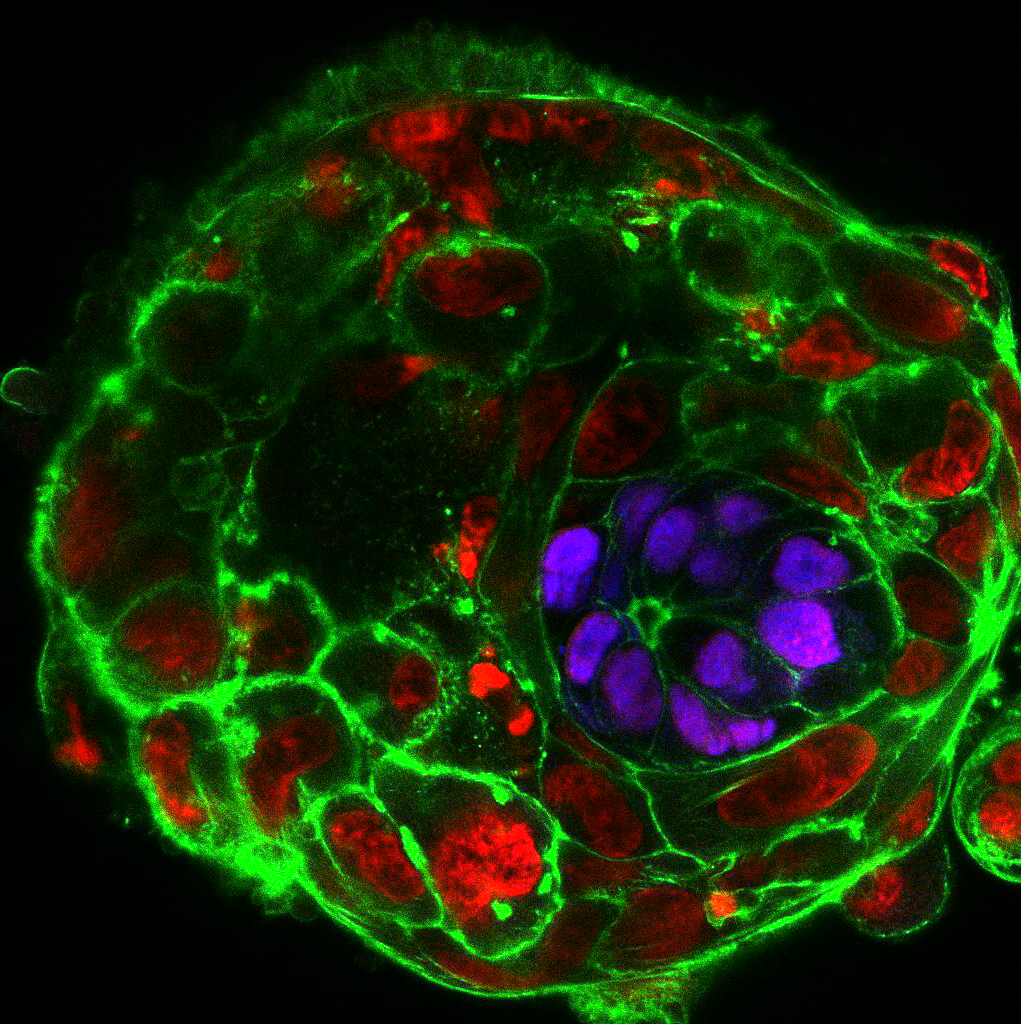

At a session chaired by Roger Highfield, Director of External Affairs of the Science Museum Group, advances in fertility science were discussed by Dr Evan Harris, the former MP who scrutinised the HFE Act 2008; Dr Andy Greenfield, Principal Investigator and Programme Leader in Mammalian Sexual Development at the Medical Research Council Harwell Institute’s research centre; and Dr Kathy Niakan, Group Leader of the Francis Crick Institute’s Human Embryo and Stem Cell Laboratory, the first researcher licensed by the HFEA to edit the genomes of human embryos.

Genome editing dominated headlines around the world the week of the conference when He Jiankui of Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen claimed to have created the world’s first genome-edited babies in an attempt to confer resistance to HIV, the AIDS virus.

Dr Niakan said that the development was concerning, and, if confirmed, would mark an irresponsible, unethical and dangerous use of genome editing technology. ‘In the UK, it is rightly illegal to establish a pregnancy from a genome-edited embryo. Given the significant doubts about safety, including the potential for unintended harmful side-effects, it is simply far too premature to attempt this.’

She also pointed out that ‘…the sparse technical details suggested that there does seem to have been a genetic change in these infants but it fell short of the precision that one would expect from genome editing. Moreover, creating “genomic immunity” to HIV infection was a weak justification for genome editing because there are still too many unknowns concerning the technology and human embryonic development.’

Dr Andy Greenfield attended the International Summit on Human Genome Editing where the controversial work was unveiled. He said: ‘There was an electricity in the auditorium unlike anything I have experienced in my scientific career…. I sensed so many apparent contradictions. He (He Jiankui) did not once admit any wrongdoing; he carefully explained what he had done and why. His aim had been to generate humans with an altered version of a particular protein, CCR5, which if disrupted would confer immunity to HIV infection.’

Dr He had, he believed, followed appropriate protocols in obtaining informed consent from the parents. ‘He had also sought and was given appropriate institutional authority to proceed – but neither of these statements convinced many in the audience,’ said Dr Greenfield.

Many questions remain, not least the need to independently verify the data that He Jiankui presented, whilst protecting the identity of the children. As yet, the data have not appeared in a peer-reviewed journal.

The panel was also concerned by the impact of the announcement in terms of public confidence. Dr Harris said that ‘…it is important to keep pushing for progress. If we don’t talk about issues for fear of controversy the only voices being heard will be those seeking to restrict or ban.’

Sarah Norcross, Director of the Progress Educational Trust, said the news was shocking on many levels. ‘First, we would have expected to see a lot more research into the safety and efficacy of genome editing in human embryos, before attempting to achieve a pregnancy. Second, we would have expected the first such application of genome editing to be on an embryo which had a serious genetic condition with life-limiting consequences. Given our current level of knowledge, editing the genomes of healthy embryos to attempt to confer resistance to HIV is completely unethical.’

A more accurate kind of genome editing, unveiled in 2012, exploits a mechanism used as a defence against viral attack by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes. It is known as CRISPR mutagenesis, an acronym that comes from the repetitive DNA sequences (‘clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats’) that form the bacterium’s immune system with a set of enzymes called Cas (CRISPR-associated proteins) that, guided by RNAs copied from invading viruses, can cleave the invading viral DNA to stop the viruses from replicating.