Gladys West is a mathematician most famous for her work on the development of the Global Positioning System, best known as GPS. Using advanced mathematics along with computational algorithms, Gladys devised an intricate model of the shape of the Earth, which underpins the way GPS works. GPS was the world’s first satellite navigation system, and revolutionised the way we locate ourselves in and travel through the world. Today, it’s used by an estimated 3 billion people worldwide.

As a Black woman born under racial segregation in rural America, Gladys overcame tremendous obstacles in her life, and her work has transformed our everyday lives.

Gladys was born Gladys Mae Brown in Sutherland, Virginia, on 27 October 1930. She came from an African American farming family: in her community, the only two career paths for young girls were farming, or working at a tobacco processing factory. Although her parents hadn’t had the opportunity to continue schooling beyond elementary level (about the age of 10), education was very important to them, particularly her mother. Gladys had to help out on the family farm when she wasn’t studying, but from a young age she knew farming wasn’t for her. She was determined to make it out of small-town rural Virginia – and education was the key.

With her parents’ support, Gladys was able to attain high grades across all her subjects at high school. Her high attainment not only gave her the pick of any subject to specialise in, but secured her a full scholarship, without which she wouldn’t have been able to afford to go to college. She attended Virginia State College, a historically Black public university, where she majored in mathematics, a subject mostly studied by men at the time. While her scholarship covered tuition fees, she needed extra funds to live on while she studied, so she took on part-time work as a babysitter. Gladys graduated in 1952, and was keen to keep expanding her knowledge: she spent a couple of years working as a maths teacher to save up enough money to return to Virginia State for a master’s degree in mathematics, which she obtained in 1955.

The following year, she began what would become a lifelong career with the US armed forces with a job at the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia. She was only the second Black woman to be hired there, and one of four Black employees at the time. She had initially turned the job down, believing that she might be rejected at the interview due to her race, but the Proving Ground administration reached out again, offering her the job without needing to interview solely based on her outstanding qualifications. This kind of job and the financial security it offered was a rare opportunity for an African American woman, especially in the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, a nation-wide campaign against racial segregation, and fighting equal rights for African Americans.

Gladys worked there as a mathematician, undertaking the complex calculations needed for the research conducted at the facility. Later, she worked on large-scale computers to analyse satellite data, and she continued to progress in this area, working on a number of projects over the years. It was working at Dahlgren that she met her husband, Ira West. They married in 1957, and went on to have three children.

In the mid-1970s, work had begun in earnest on the development of the Global Positioning System, or GPS. As many innovations, the development of GPS was born from military needs: the project was founded by the US Department of Defence as a navigation system for soldiers and military vehicles. To this day, while now available for civilian use, it’s administered by the US Air Force.

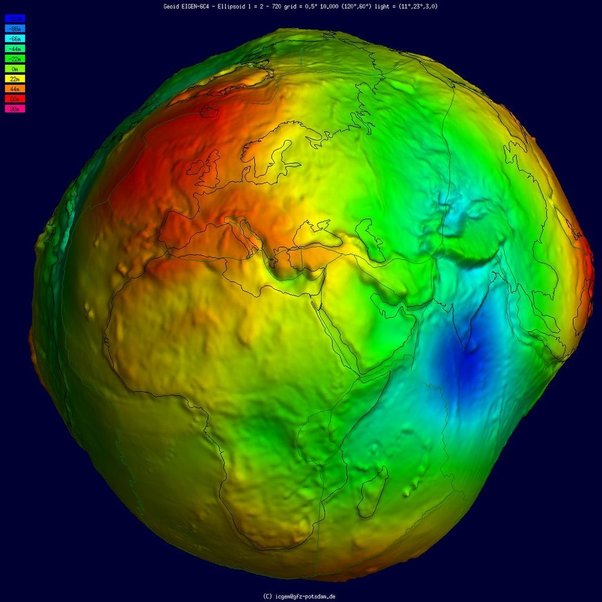

GPS uses a network of satellites and ground stations to allow receivers to calculate their location from anywhere on Earth. The relationship between the Earth’s surface and satellites is crucial: every satellite must calculate its own location in relation to the ground stations, and pass that on to the receivers, which then calculate their own location with respect to the satellites. For these calculations to be possible, the system needs an accurate model of the shape of the Earth, with all its contours and elevations.

Gladys West programmed a computer to produce such a model. It used data from surveying satellites with equations to represent the forces acting on the Earth that distort its shape, such as gravitational and tidal forces. This model, known as the geoid, underpinned the function of GPS, allowing for the precise calculations of any location on Earth.

Gladys went on to publish further research on improving accuracy in satellite surveying, and continued her computing programming and research at Dahlgren until she retired in 1998, having worked there for 42 years.

However, her career didn’t end with retirement. Gladys obtained a PhD in Public Administration in 2000, at the age of 70. In 2018, she was formally recognised for her contributions to GPS by the Virginia General Assembly, the state’s legislative body. That same year, she was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame. She and her husband Ira still live in Virginia, and are strong advocates for education- mentoring elementary school students to improve their reading skills, and founding a scholarship programme in collaboration with Dahlgren to support high school students going into Science, Technology, Engineering or Maths (STEM) subjects.