Over a 20-year period from the mid-1960s, Soviet scientists and engineers conducted one of the most successful interplanetary exploration programmes ever.

They launched a flotilla of spacecraft far beyond Earth and its Moon. Some failed, but others set a remarkable record of space firsts: first spacecraft to impact another planet, first controlled landing on another planet and the first photographs from its surface. The planet in question was not Mars – it was Venus.

Our knowledge of Venus at the time had been patchy. But as the Soviet probes journeyed down through the Venusian atmosphere it became clear that this planet – named after the Roman goddess of love – was a supremely hostile world. The spacecraft were named Venera (Russian for Venus) and the early probes succumbed to the planet’s immense atmospheric pressure, crushed and distorted as if made of paper.

Venera 3 did make it to the surface – the first craft ever to do so – but was dead by the time it impacted, destroyed by the weight of the air. Venera 4 was also shattered on the way down, but it survived long enough to return the first data from within another planet’s atmosphere. The engineers realised, though, they would have to reinforce still further the spacecraft’s titanium structures and silica-based heat shield.

The information coming in from the Venera probes was supplemented with readings from American spacecraft and ground-based observatories on Earth. Each added to an emerging picture of a hellish planet with temperatures of over 400 °C on the surface and atmospheric pressure at ground level 90 times greater than Earth’s.

Spacecraft can only be launched towards Venus during a ‘window of opportunity’ that lasts a few days every 19 months. Only then do Earth and Venus’ relative positions in the Solar System allow for a viable mission. The Soviets therefore usually launched a pair of spacecraft at each opportunity. Venera 5 and 6 were launched on 5 and 19 January 1969, both arriving at Venus four months later.

There had not been time to strengthen these spacecraft against the unforgiving atmosphere, so instead the mission designers modified their parachutes so that they would descend faster and reach lower altitudes, sending back new data before their inevitable destruction.

Launched on 17 August 1970, Venera 7 made it intact to the surface of Venus on 15 December 1970 – the first probe ever to soft land on another planet. Its instruments measured a temperature of 465 °C on the ground. It continued to transmit for 23 minutes before its batteries were exhausted.

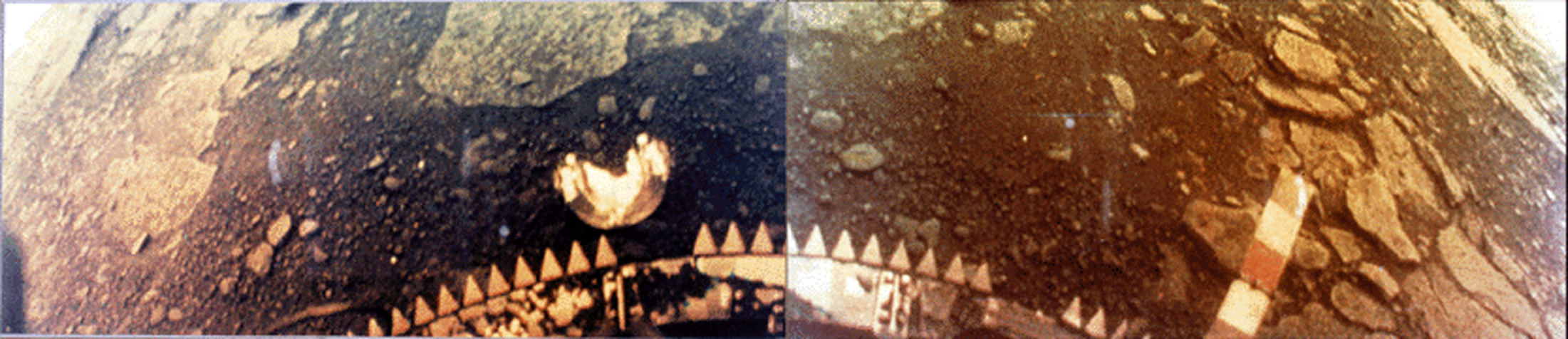

Venera 8 carried more scientific instruments which revealed that it had landed in sunlight. It survived for another 50 minutes. Venera 9, the first of a far stronger spacecraft design, touched down on 22 October 1975 and returned the first pictures from the surface of another planet. It too showed sunny conditions – comparable, the scientists reckoned, to a Moscow day in June.

The surface was shown to be mostly level and made up of flat, irregularly shaped rocks. The camera could see clearly to the horizon – there was no dust in the atmosphere, but its thickness refracted the light, playing tricks and making the horizon appear nearer than it actually was. The clouds were high – about 50 km overhead.

The Soviet Union now had a winning spacecraft design that could withstand the worst that Venus could do. More missions followed, but then in the early 1980s, the designers started making plans for the most challenging interplanetary mission ever attempted.

Credit: NASA History Office

Scientists around the world were keen to send spacecraft to Halley’s Comet, which was returning to ‘our’ part of the Solar System on its 75-year orbit of the Sun. America, Europe and Japan all launched missions, but the Soviets’ pair of Vega spacecraft were the most ambitious, combining as they did a sequence of astonishing maneuvers, first at Venus and then at Halley’s Comet.

Both crafts were international in their own right, with many nations contributing to their array of scientific instruments. They arrived at Venus in June 1985.

Each released a descent probe into the Venusian atmosphere. Part of it released a lander that parachuted down to the surface while the other part deployed a balloon, with a package of scientific instruments suspended underneath that first dropped and then rose through the atmosphere to be carried around the planet by winds blowing at well over 200 miles per hour.

Meanwhile, the main part of each Vega spacecraft continued on past Venus, using the planet’s gravity to slingshot itself towards an encounter with Halley.

A little under a year later both arrived a few million kilometers distant from the comet. Both were battered and damaged by its dust, but their instruments and cameras returned plenty of information on the ancient, icy and primordial heavenly body.

A golden age of Russian planetary exploration had come to an end.

Russia plans to return to Venus, but meanwhile, its Vega spacecraft, their instruments long dead, continue to patrol the outer reaches of the Solar System, relics of the nation’s pioneering days of space exploration.