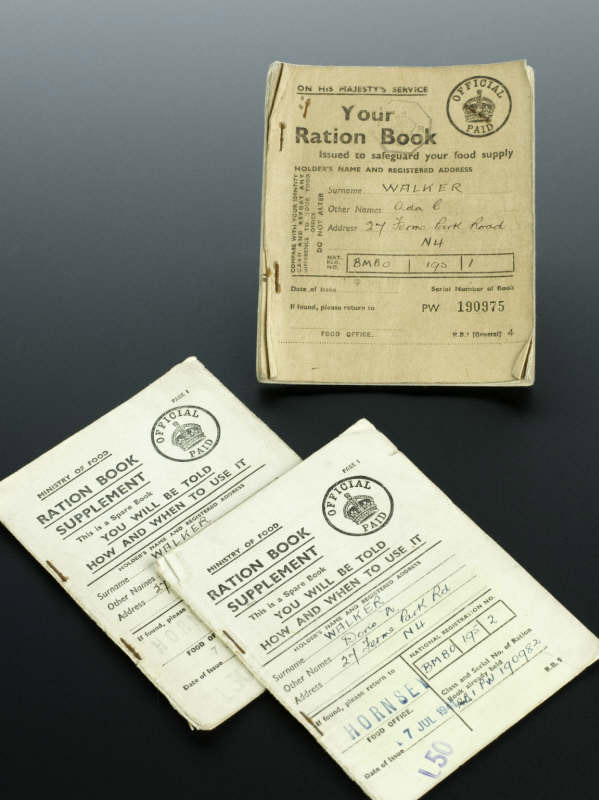

The Second World War challenged the health of the home population as well as the fighting services. Even before the war, Britain depended on a huge quantity of imported goods, including food. Enemy ships targeted incoming Allied merchant vessels sending their precious cargo to the depths of the Atlantic. As various items became scarce, food consumption was rationed.

Winston Churchill was keen, wherever possible, to limit austerity in the interests of morale. Even his scientific adviser, the teetotal Frederick Lindemann, was glad that the Ministry of Food undertook to provide the normal stocks of beer.

This period saw the rise of a small group of scientists whose experimental research helped ensure people had enough food to survive.

Pioneering studies assessed the impact of rationing and established a healthy balance of available foods. Nutritionists Robert McCance and Elsie Widdowson led this investigation. Their task was to see how far food produced in Britain could meet the needs of the population and how much shipping could be saved.

Both scientists were familiar with self-experimentation before the war, having explored the chemical make-up of food and its effect on human health. Their book, The Composition of Foods was first published in 1940 and became a standard work in the field of nutrition.

This task was no different. Funded by the Medical Research Council, McCance, Widdowson and a small group of volunteers drastically reduced their intake of food and drink to a level some considered ‘intolerable’. Although wholemeal bread and potatoes were unrationed, each person was allowed the following quantities per week: 110g fat, 150g sugar, one egg, 110g cheese, 450g meat and fish combined and quarter of a pint of milk a day.

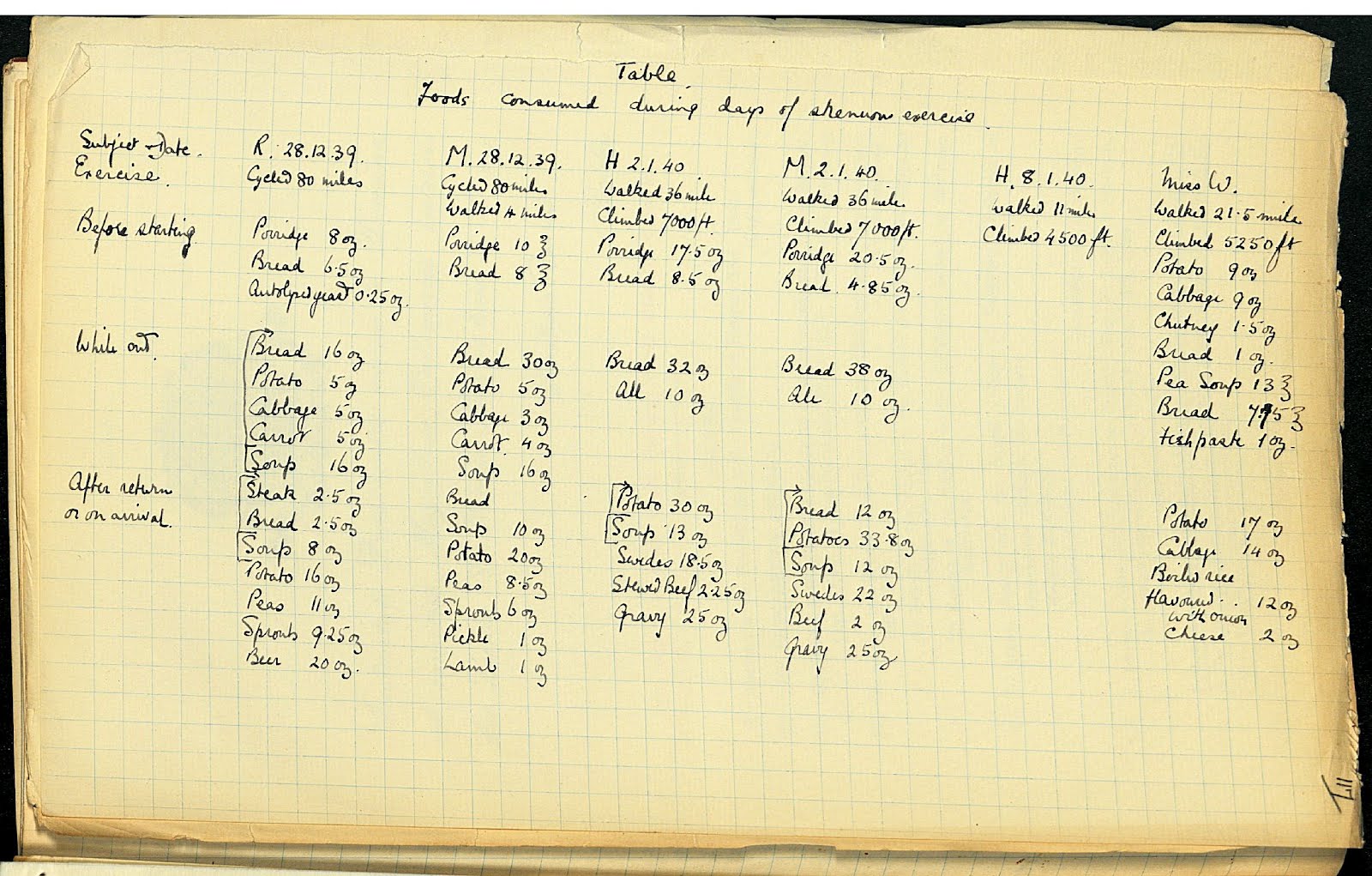

After enduring this diet for three months, the volunteers moved to the Lake District for the second stage of their experiment. In chilly December 1940, the team proved that by enduring gruelling climbs, hikes and bicycle rides, this basic diet could meet the nation’s health needs.

One of McCance and Widdowson’s most important findings was the risk of calcium deficiency from a diet low in dairy products. Their recommendation for fortifying bread with calcium carbonate (chalk) was met with criticism, but later made law. McCance and Widdowson’s work was made public after the war with their book, An Experimental Study of Rationing, published in 1946.

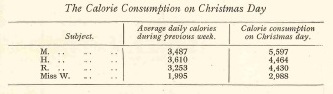

The book shows that even in the hardships of McCance and Widdowson’s experiment, they celebrated Christmas with a hearty meal as their ‘calorie intake was affected by comfort and good cheer’. There was a plum pudding made from ingredients saved from the previous week’s rations and McCance ate five large potatoes ‘more than he had ever eaten in one day before’. This may sound familiar, but he had cycled for 52 miles the day before!

As you tuck into your plate of turkey, pigs-in-blankets, roast potatoes and that token Brussels sprout, spare a thought for those intrepid nutritionists whose experiments ensured people had enough food on their tables during the Second World War.

Rachel Boon is the Content Developer for Churchill’s Scientists. This free exhibition at the Science Museum, open until January 2016.