Today (13 November 2017) is 60 years to the day since scientists launched Skylark, the first British space rocket programme. At the Science Museum we’ll be celebrating this momentous occasion with a new exhibition in our Exploring Space gallery that examines the story behind Skylark, and the engineers and scientists who built and used it.

Skylark was designed to gather data on the upper atmosphere, to help develop the Blue Streak ballistic missile. But it could also be used by university researchers to learn more about the Earth, Sun and deep space. In 1957-8 the rocket was Britain’s main contribution to the International Geophysical Year, a global project to research the physics of the Earth.

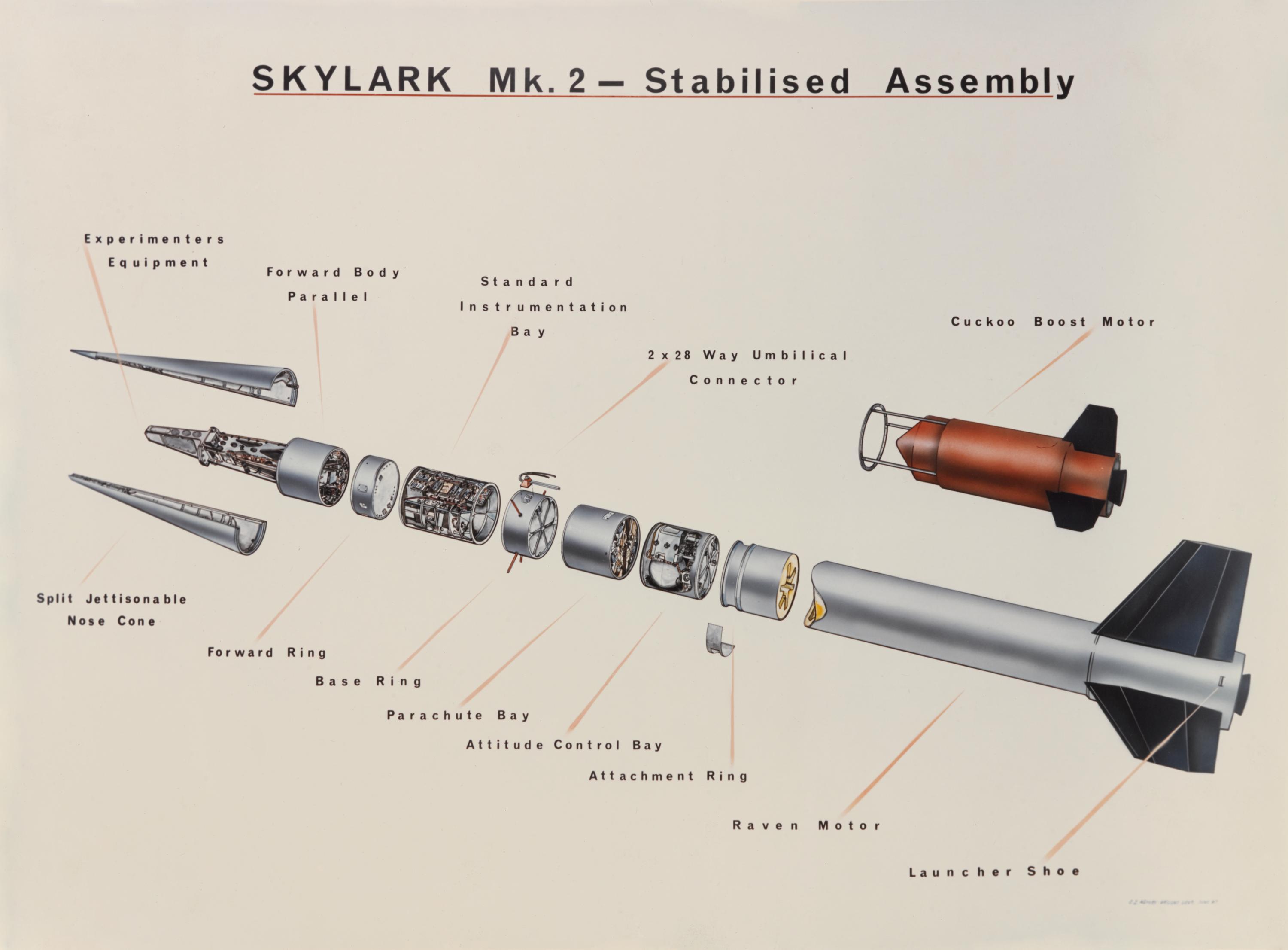

Climbing to heights of many hundreds of kilometres, way beyond the reach of scientific balloons, Skylark could perform a range of experiments during its 10-minute flight time. Most of the results would be recorded on board and then parachuted back to Earth for recovery.

It is no exaggeration to say that Skylark laid the foundations for Britain’s space activities of today, which range from world-leading space science programmes to the design and building of satellites. It conducted the first X-ray surveys of the southern sky.

Early experiments measured the temperature, density and wind direction of the upper atmosphere by detonating grenades ejected from the rocket as it climbed into the sky. In the 1970s Skylark produced some of the earliest ultraviolet images of the cosmos.

It was the relative simplicity of Skylark which proved so important in training up young space scientists. They would have hands-on experience of designing and running experiments carried aboard each rocket. Many leading space scientists, from university professors to Space Shuttle astronauts, started their space careers with Skylark.

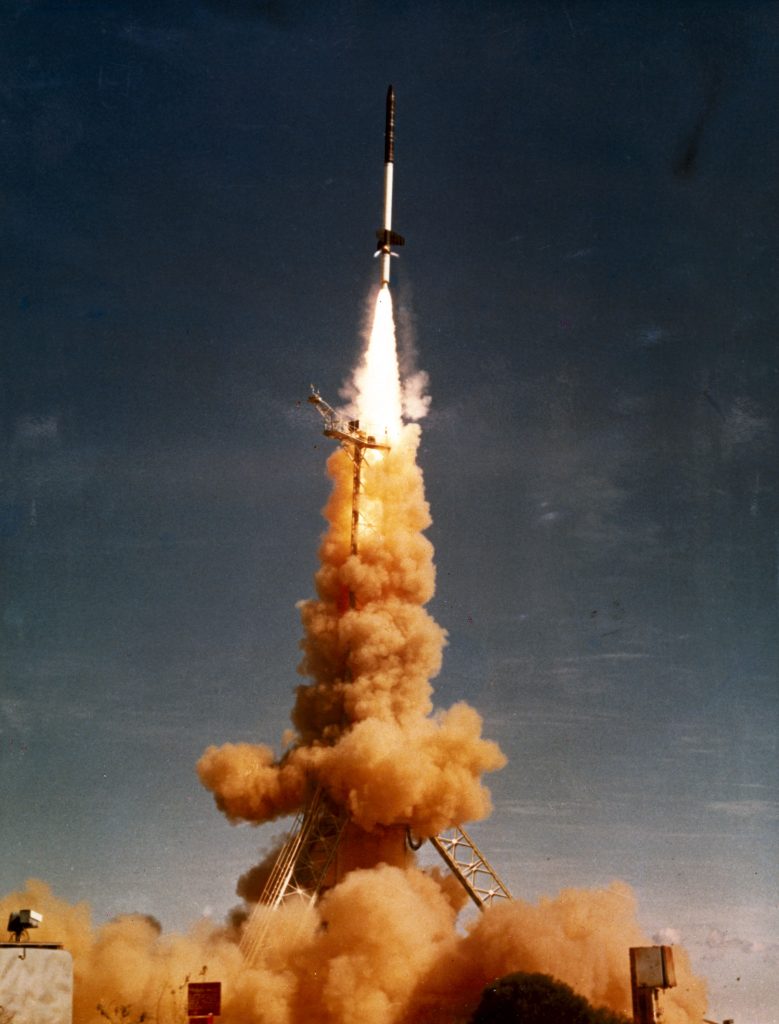

The experience could be memorable in many other ways. Most Skylarks were launched from the South Australian desert and conditions for the young teams there could be challenging. The heat was intense but when it (very occasionally) rained the desert bloomed only to generate plagues of locusts and budgerigars.

The name Skylark replaced the rather uninspiring CTV5 Series 3. A scientific officer working on the early programme felt the rocket needed a catchier name and so drew up a long-list of equally unlikely alternatives that ended with ‘Skylark’ – which was duly chosen.

Over almost half a century a total of 441 Skylark rockets were launched, making it one of the longest and most successful programmes of its kind in the world.