Roger Highfield, Director of External Affairs explores a new online intelligence test with an AI twist.

So many key questions about intelligence remain unanswered that it seems that the human brain is ill-equipped to fully understand itself.

Now a team at Imperial College London has created the first artificial intelligence designed to survey human mental skills. You can put your intelligence to the ultimate test and see how you fare compared with others by visiting the Cognitron website here.

Over a period of half an hour the AI will put you through a series of customised tests and, after you have supplied a few details, tell you how well you performed.

Information gleaned from around 200 people at a time will be analysed by the AI to progressively improve its repertoire of brain teasers, you can read the full story in the latest issue of Wired, online today.

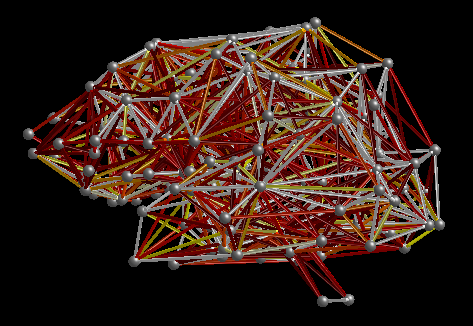

The AI developed by a team of psychologists, neuroscientists and engineers at Imperial’s Computational, Cognitive and Clinical Neuroimaging Laboratory, ‘C3NL’, depends on Bayesian Optimization. This system is named after the 18th-century Presbyterian minister Thomas Bayes, who devised a systematic way of calculating from an assumption the way the world works and what how the likelihood of something happening changes as new facts emerge.

In this mass experiment, the Imperial team hopes to follow up an earlier online test by Adam Hampshire, Adrian Owen from Cambridge’s Cognition Brain Sciences Unit and myself, when I edited New Scientist.

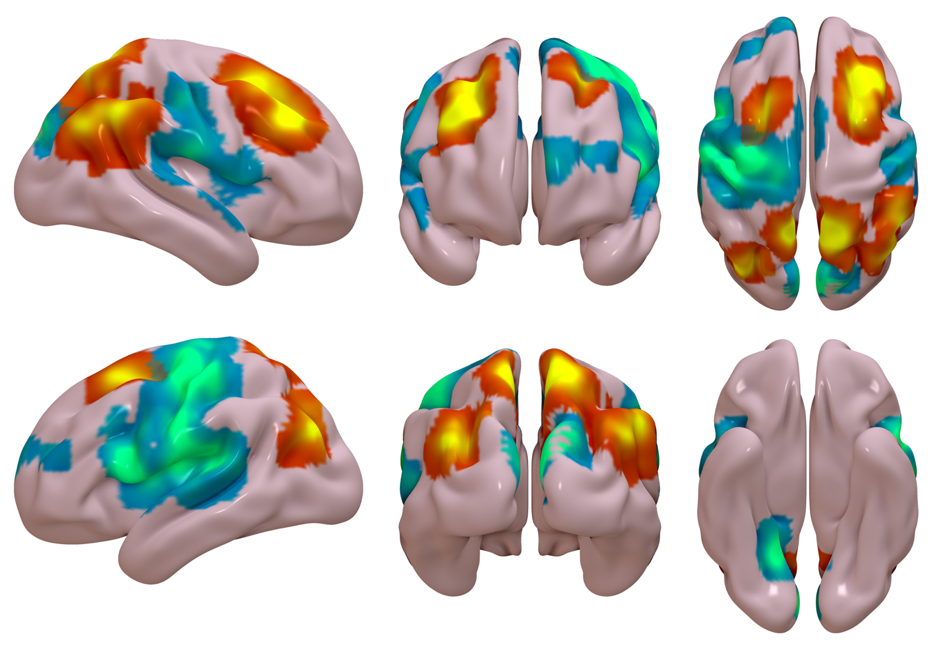

We were amazed when more than 100,000 people took part, and published the results in 2012 in the journal Neuron. Based on the data gathered, Adam Hampshire’s statistical analysis suggested that a single number, IQ, could not capture all facets of human intelligence and that at least three factors were needed: short-term memory; reasoning; and, finally, a verbal factor, (read the blog post we published back in 2012 for more).

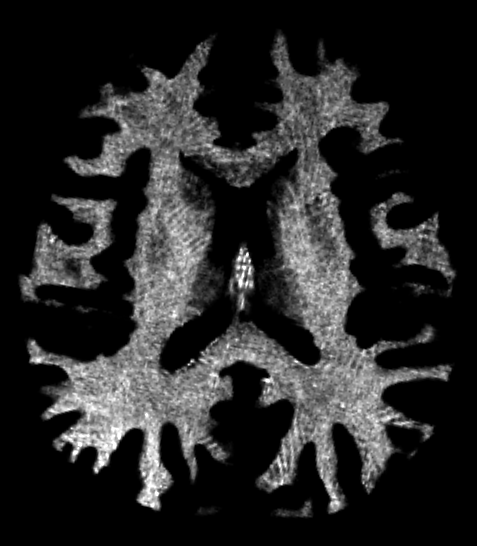

Were these three factors underpinned by three brain circuits? Different circuits did indeed seem to be involved when the Canadian team did a follow-up study of 16 people with a $5 million fMRI scanner. In a way we had distilled intelligence into fractions.

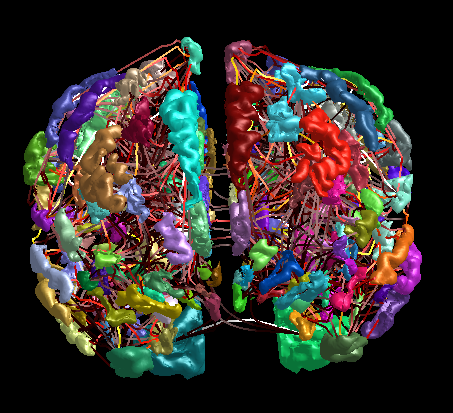

The idea that general intelligence rests on collaborating circuits had been suggested before, notably by John Duncan at the Medical Research Council’s Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge. Two of our intelligence factors – working memory and reasoning – corresponded to circuits that Duncan had already identified as being central to human intelligence, suggesting that we were on the right track.

But a broadside published in the journal Intelligence concluded that our results ‘depend on a number of assumptions and subjective decisions that, at best, allow for different interpretations. Ultimately, we as humans are not unbiased enough’ remarked Romy Lorenz.

To remove subjectivity, she and her Imperial supervisor Rob Leech developed the Automatic Neuroscientist, with the help of Prof Giovanni Montanna from King’s College London and his doctoral student, Ricardo Pio Monti.

First, they started out with a well-understood toy problem to make sure that the AI based approach worked: could the AI present more than 300 combinations of sounds and images of varying complexity to human subjects in a brain scanner to figure out which combinations were most able to turn their visual cortex on and auditory cortex off? It did, after six minutes. Leech was ecstatic: ‘That is when we realised that it was the first general purpose Automatic Neuroscientist.’

In collaboration with Hampshire, they went on to show the power of the Automatic Neuroscientist with a pilot brain imaging study on 21 volunteers from their lab who performed 16 different cognitive tasks. The machine was asked to find which brain circuits were activated by each task, including some from the 2012 Neuron paper.

Two tasks cleanly harnessed independent circuits, both from the 2012 paper: Deductive Reasoning, when subjects have to spot the ‘odd one out’, and the Tower of London task, where they are shown a tree-like frame festooned with numbered beads, then asked to put the beads in the right order. Confirmation of two of the three circuits identified by the 2012 paper was encouraging but, as Hampshire says, probably “sheer, blind, luck.”

Still, many of their peers are impressed with the Automatic Neuroscientist.

‘This framework is very promising,’ comments Thomas Yeo of the National University of Singapore, who uses machine learning in brain imaging. It is ‘strikingly innovative,’ adds Chris Gorgolewski of the Stanford Center for Reproducible Neuroscience, who thinks it could be extended to make neuroscience more automated and thus more reproducible.

The work is ‘potentially very exciting,’ adds John Duncan. ‘Experimental psychology has always been dogged by uncertainty over how well findings generalise from one apparently similar task to another.’ Peter Coveney of University College London, critic of the blind application of machine learning to big data, adds: ‘This is an eminently sensible approach, combining underpinning hypotheses of brain function with machine learning to highly effectively reveal unexpected modes of human thought.’

To turn the AI into a cloud-based test that could be done online, the team worked with Pete Hellyer, a Wellcome Trust fellow at C3NL, along with William Trender. The aim of the new online study launched today is, as Hampshire puts it, to see if they can ‘develop an AI machine that can work out the major components of human intelligence, that is completely unbiased, with large amounts of data and by harnessing the ability to learn in an iterative manner.’

The ramifications are even broader. Leech believes machine intelligence can erase subjectivity from research. Machines could design and run experiments and help usher in a better way to do science. No wonder that it has been backed by the Medical Research Council and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Visit the Cognitron website and help the Imperial team discover if artificial intelligence really is the key to understanding human intelligence.