2015 is the 350th anniversary of the publication of Micrographia by Robert Hooke. A contemporary of Sir Isaac Newton, Hooke was Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society and Professor of Geometry at Gresham College. In January 1665, Samuel Pepys described Micrographia as “…the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life….”

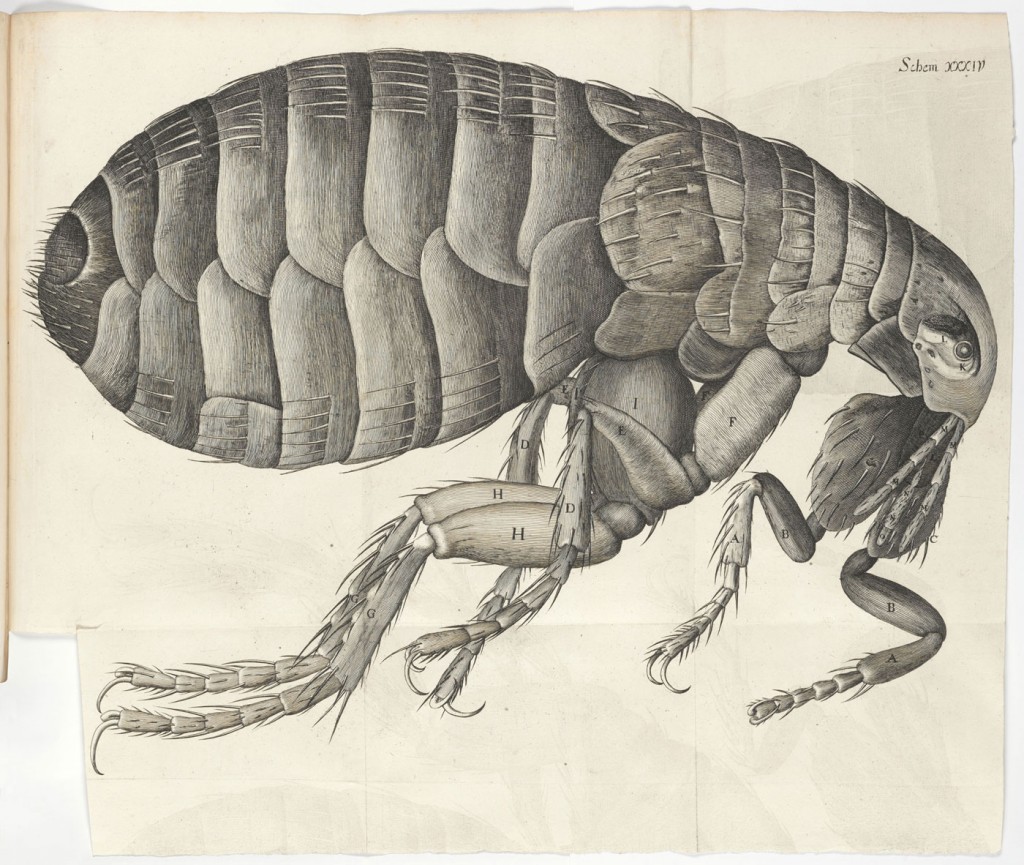

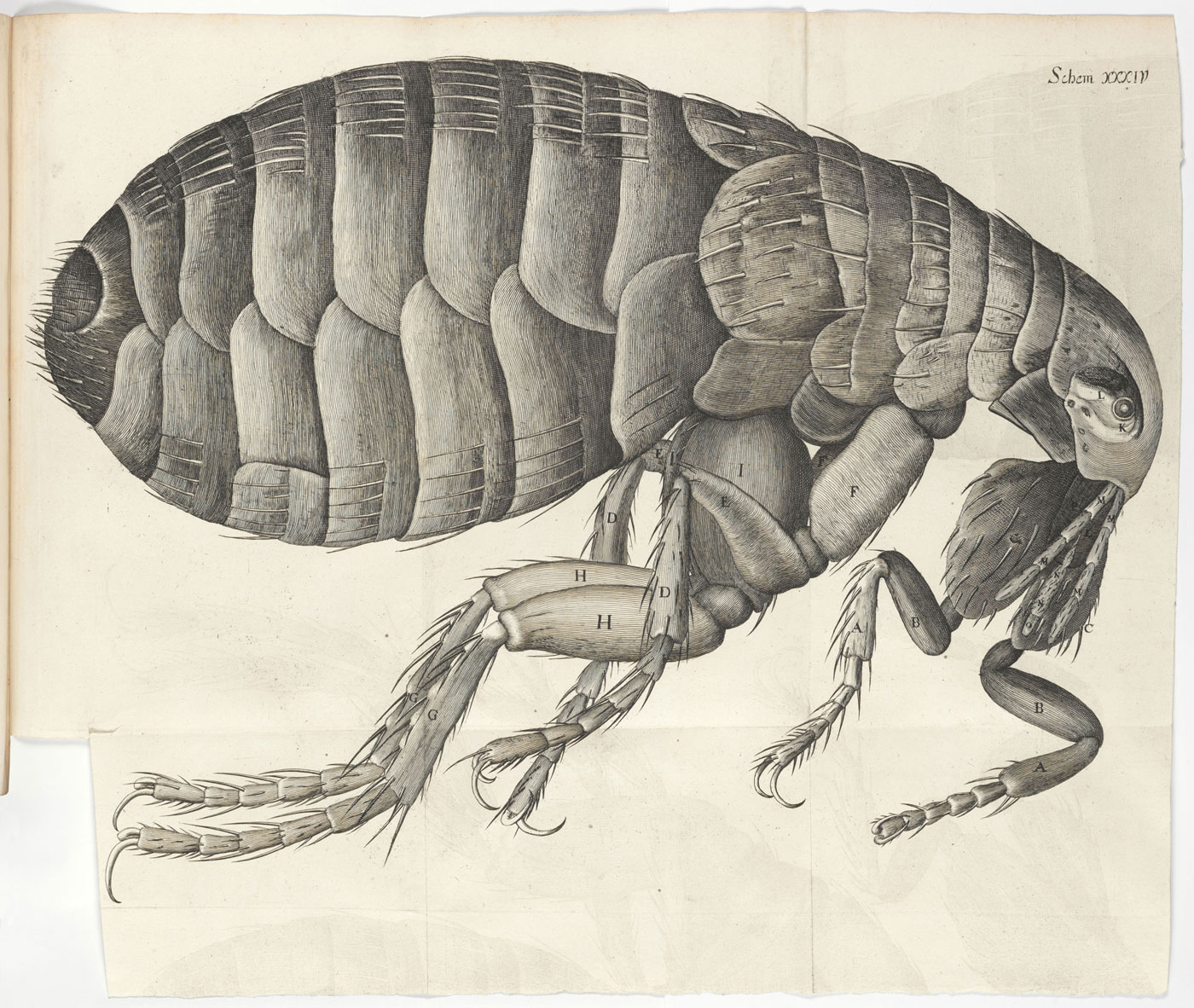

Pepys’ enthusiasm was genuine. For many readers in the mid-seventeenth century, this was the first time they had seen large-scale illustrations of tiny creatures from everyday life. These were beings such as fleas, mites, and ants that appeared as specks to the naked eye, but were revealed by the microscope to be as intricate as larger animals.

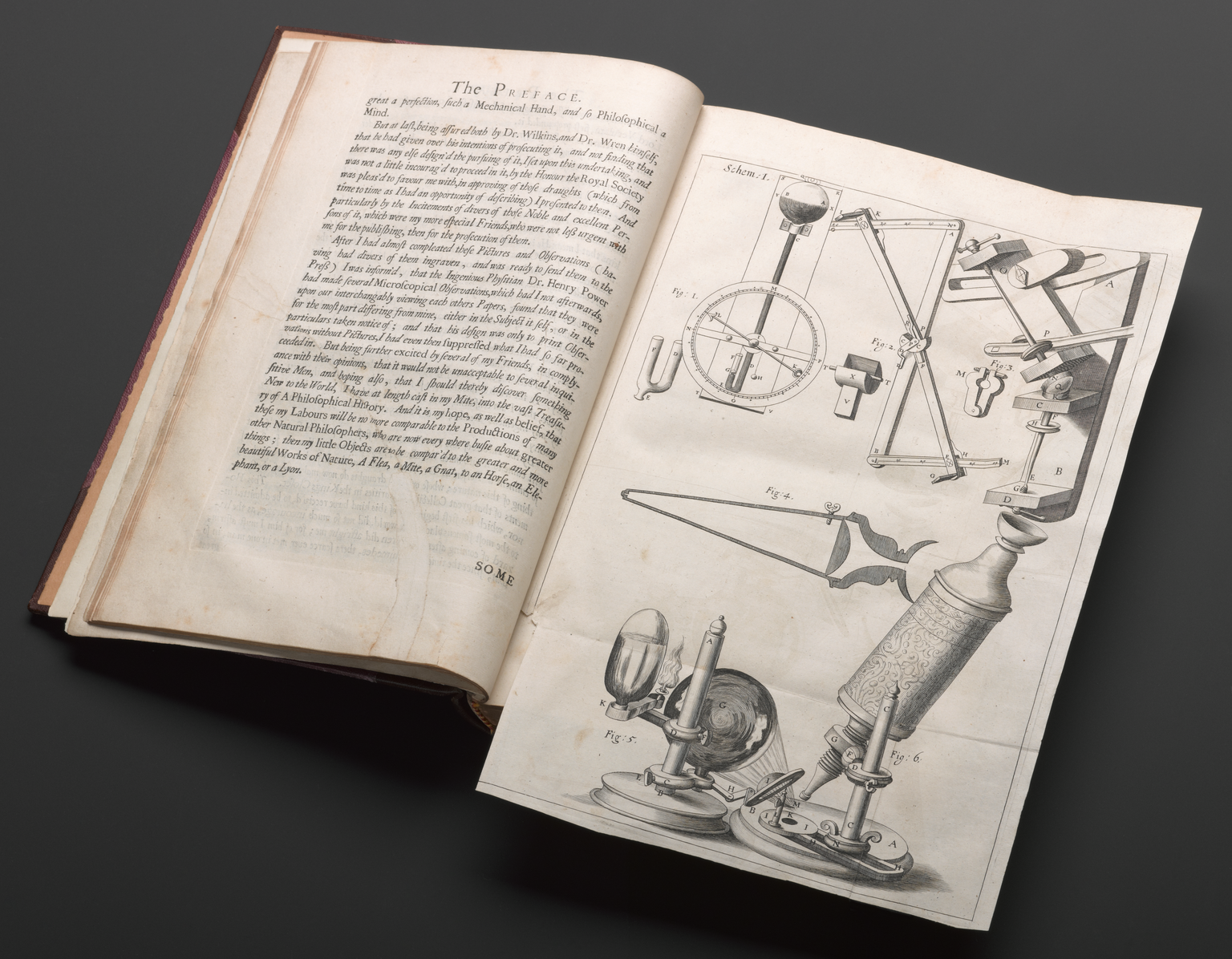

One way of celebrating this anniversary is by presenting two modern copies of the microscope illustrated by Hooke in Micrographia. For me, their existence represents our enduring fascination with both Hooke and the history of microscopy. The Science Museum’s Journeys of Invention app showcases a microscope believed to have belonged to Hooke in 1675, but this was not the one illustrated in Micrographia in 1665.

Microscope 1927-437 is part of the Science Museum’s permanent collection. It was purchased in 1927 from Thomas Henry Court, who had a great interest in early scientific instruments and presented a large collection to the Museum in the 1930s.

A memo written in May 1927 by a Curator at the Museum records a meeting with Court. In this document, the microscope is described as a “…full-size copy of Robert Hooke’s original compound microscope as described in his ‘Micrographia’, 1665.” According to Court, it was previously owned by Mayall.

We know that John Mayall made copies of seventeenth-century microscopes in the 1880s, which suggests that he may have made this one. Mayall shared his deep interest in the history of the microscope in his Cantor Lectures (published in 1889). Although a replica, this object is useful to us because, unlike the illustration, its three-dimensional form enables the viewer to rotate it and look at it from different angles.

Taken alongside Hooke’s words: “I make choice of some room that has only one window, on a table, I place my microscope…”, we can imagine Hooke using it while making notes and illustrations of what he could see.

Microscope A601160 is part of the Wellcome Collection and was made by W.G. Turner between 1901 and 1917, of whom no further information was found. We do know that Turner, like Mayall, made a number of replicas of early microscopes.

Within the Wellcome Collections are replicas of Campani’s microscope and two of Cherubin d’Orleans’ microscopes. Although, not as ornate as microscope 1927-437, it is important as it represents a desire to understand Hooke’s work within the context of other seventeenth-century individuals such as Campani and Cherubin d’Orleans. It also suggests an attempt to compare the microscopes of England with those of Italy and France in the period.

For the authors of London’s Leonardo: The Life and Work of Robert Hooke, Bennett, Cooper, Hunter and Jardine, Hooke was immensely optimistic about the future and human capability. This was an important characteristic of the beginnings of modern science. I think it was this great enthusiasm and optimism, which later historians strove to get a glimpse of when they made and studied copies of Hooke’s microscopes. In this particular case replicas were not intended to deceive; they were made as an aid to thinking about early science.

This post was originally published in 2015. You can now see Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and a Hooke-type telescope on display in our newest permanent gallery Science City 1550-1800: The Linbury Gallery.

One comment on “The Micrographia Microscope”

Comments are closed.

I can’t imagine the shock on the first person who saw a mite under the microscope