I am currently away from the Science Museum on a study sabbatical and was fascinated to find that my historical research chimes with contemporary debates, notably about the purpose, safety and effectiveness of vaccines, our key line of defence against COVID-19.

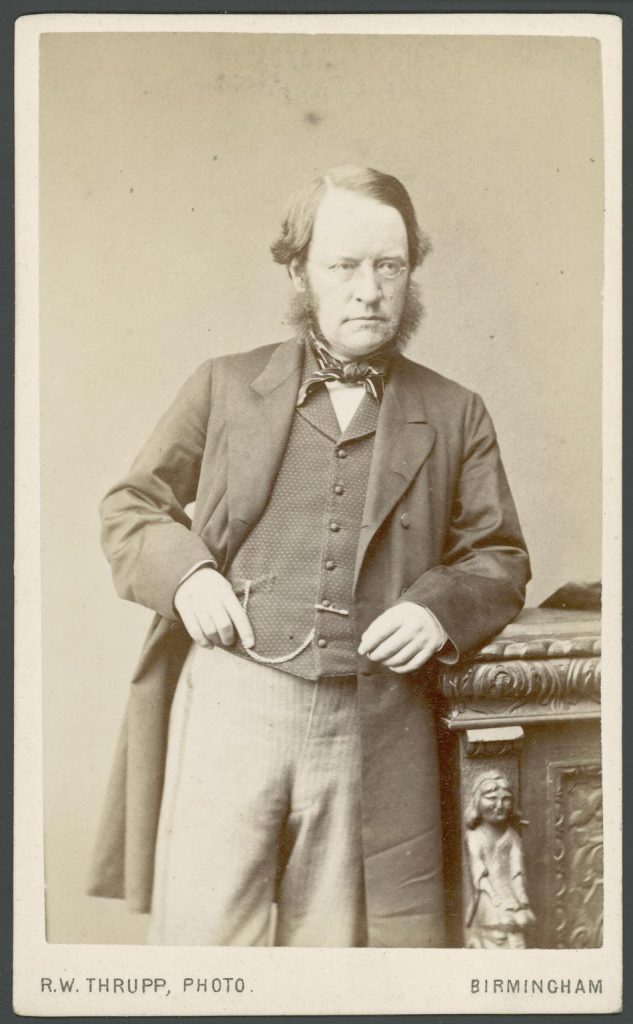

My research centres on the life of the eminent Victorian scientist and politician Lyon Playfair (1818-1898) and his early career is explored in a recently published article in the Science Museum Group Journal.

Playfair played a crucial role in promoting the status of science and scientific education in Britain and was a figure of considerable stature. Although the British state had no formal role of Chief Scientist, it could be argued that Playfair was seen by many as a ‘consultant scientist’ to the government and so a forerunner to the current role held by Sir Patrick Vallance.

Playfair was a trusted adviser to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, admired by leading scientists at home and abroad, close to all the major political leaders, and friendly with writers such as Charles Dickens, George Eliot and Henry James.

During a long life in public service, he was also a leading player in a remarkable range of government commissions ranging from mine safety to the relief of poverty in old age. During his time as a Member of Parliament he also enjoyed ministerial roles in several administrations of the Liberal governments led by Gladstone and was such a passionate social reformer that admirers described him as ‘an advanced Liberal’.

Playfair was a man of influence, and a compelling orator in Parliament. One of his many passions was vaccination and he was to become the most prominent opponent of the Anti-Vaccination League.

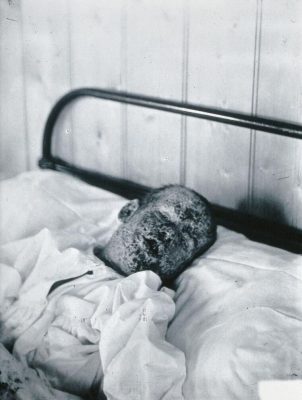

His belief in vaccination rested on the incredible work of Edward Jenner and his smallpox vaccine, and from vivid experience of the disease in this country and Europe (you can see some of Jenner’s instruments and learn more about this disease in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries at the museum). Smallpox was a major cause of death and those who survived it still risked blindness and disfigurement.

Playfair had seen the evils of a major smallpox outbreak in his native Scotland in 1871-73 and the widespread, if panicked, vaccination programme that followed; a programme that had largely eradicated the disease, providing compelling evidence it might be conquered by a concerted public inoculation programme.

Playfair’s network of contacts with the leading Continental scientists also meant that he was well informed about the serious smallpox outbreaks that followed the Franco-Prussian war of 1871, with the disease spreading rapidly amongst the unvaccinated conscripted French army whilst not impacting on the vaccinated professional German soldiers; a long way from a modern randomised control trial but this ‘trial’ was as telling as it was tragic.

To understand Playfair’s role as champion of vaccination one needs a little background on smallpox legislation.

The Vaccination Act of 1853 made it compulsory for infants under three months old to be vaccinated. Local registrars of births, marriages and deaths gave out vaccination certificates to parents of newborns which had to be returned signed by a doctor. Negligent parents could be fined or imprisoned.

In 1867, the government increased its efforts and made it compulsory for all children under the age of 14 to be vaccinated against smallpox. The law was further tightened in 1871 but whatever the medical gains, for some Victorians these laws marked an infringement of civil liberties for the sake of improving public health and the abiding idea of laissez-faire was central to economic life.

A formal pressure group, the Anti-Vaccination League, was formed in London after the Act of 1853. Later the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League was founded in 1867 in response to the new law and it argued through its well-organised public campaigns that vaccination was an infringement of personal choice.

In the 1870s and 1880s, a host of anti-vaccination pamphlets, books and journals were printed to spread the protest movement’s message including their paper, the Vaccination Inquirer.

Whilst we worry about the ferocity of social media discourse today, we forget that feelings ran just as high more than a century ago in the vaccination debate. The Inquirer conveniently confused correlation and causation (always guaranteed to infuriate epidemiologists), pumped out ‘testimony’ to the dire medical and moral side effects of vaccines and promoted alternative narratives about the physical effects of the disease.

The vaccine was accused of causing eczema, erysipelas, and sight defects, and indeed so many children had been vaccinated that it was all too easy to attribute almost any illness that developed thereafter as being the product of vaccination.

Campaigners seized upon the risk of passing on syphilis in particular: as vaccination became increasingly widespread, vaccine institutes sometimes used lymph (the pale fluid found in our lymphatic system) from one patient to vaccinate others.

If the first patient had congenital syphilis, then there was a chance of passing on the disease; and in an age that regarded syphilis disease with moralising shame, the prospect of infecting children would have been alarming.

By the summer of 1883, the campaigners were confident of victory in Parliament and the Government was so alarmed that it decided to treat the repeal motions as an ‘open question’ for Parliament rather than risk defeat in defending the existing law.

Leading the campaign was Peter Taylor, Member of Parliament for Leicester, the city being a bastion of the anti-vaccination movement and evidenced in the editorials of the Leicester Mercury. However, fellow Liberal Member of Parliament Playfair was determined to resist.

Playfair suggested that all governments need to interfere with personal liberty and recent examples had included legislation restricting working hours which had been resisted by many labourers who benefited most from the new law.

When it came to smallpox, a balance had to be struck between private choice and the ‘omissional infanticide’ that would flow if the wider health gains were ignored. He concluded that:

This disease is just as fatal and hideous as it was in the last century, but it has been controlled by wise and beneficent laws.

Some of Playfair’s arguments have remarkable contemporary resonance. He used vivid metaphors to explain that whilst vaccines are great embankments protecting us from the tidal waves of disease, the ‘Unvaccinated are like holes in them, through which the disease will find its way’.

We can hear the same arguments today as the COVID-19 vaccination programme is ramped up to resist the Delta variant in the quest for herd immunity.

Playfair considered too the persistence of the disease in London, with outbreaks in 1871, 1877 and 1881 and the capital continues to be a complex weak spot for vaccination in 2021. London was then, as it is now, a great international centre for trade and with an ever-changing population.

The Playfair speech is also brimming with questions of evidence and risk. He addressed directly the syphilis argument by claiming that since 1853 more than seventeen million infants had been vaccinated and that transfer of syphilis had only been proven in six children.

The motion in defence of the vaccination laws was won, against all expectations, by a crushing 270 votes. It was a triumph for Playfair and the anti-vaccine campaigners were incensed.

Playfair had set out the medical evidence with great clarity and he also had an uncanny ability to anticipate the counter arguments of his opponents. He argued that they constantly shifted ground in the face of the evidence and so ‘the arguments of Anti-Vaccinators are so protean that one never knows what they are’.

Playfair’s speech was widely circulated thanks to its immediate publication in the Jarrold & Sons Household Tract Series, which had targeted the growing middle class with subjects such as How to Manage a Baby, The Power of Soap and Water, and A Model Wife.

The support for vaccination amongst leading newspapers like The Times was cited by the anti-vaccinators as evidence that their views were being suppressed, not unlike the accusations by their contemporary peers about the ‘mainstream media’.

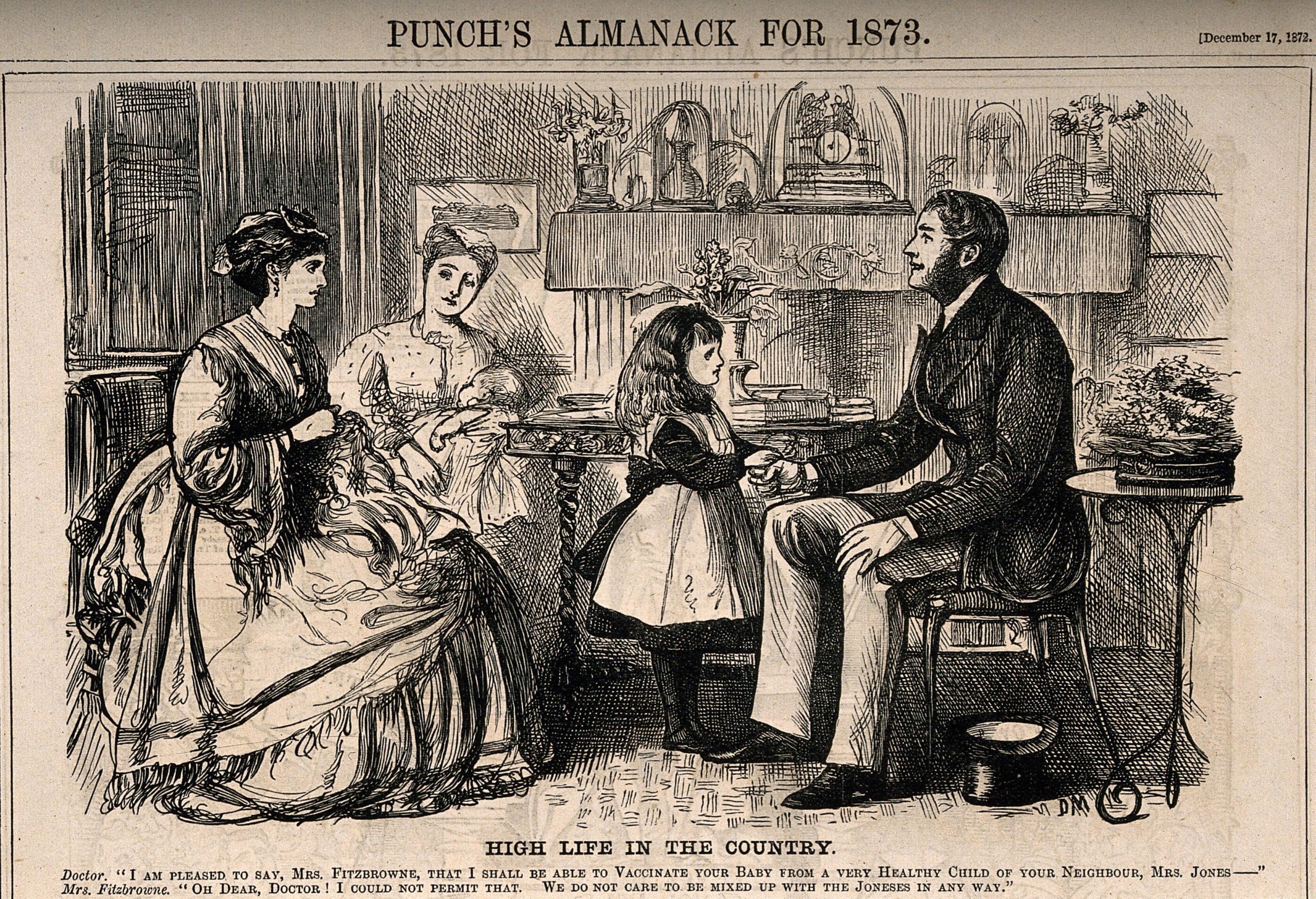

And just as infuriating to the movement was the pleasure that publications like Punch took in mocking the snobbery around vaccination, seen in the cartoon below, rather than covering the supposed safety concerns.

Playfair’s speech had certainly hit home and so was reviled by his opponents. There were many pamphlets circulated, such as the sarcastically entitled Sir Lyon Playfair’s Logic, and his speech fuelled the animosity of the Third International Anti-Vaccination Congress in Berne in September 1883.

Its main attack was published as Sir Lyon Playfair, taken to Pieces and Disposed of and amongst the ponderous statistical arguments and attempts to undermine sound medical evidence, there were also shameless attacks on his personal integrity. One slur suggested that he was simply currying favour with the significant number of the medical profession represented amongst his voters.

Ironically, Playfair had anticipated this in his own speech when he criticised the idea of some huge conspiracy – a familiar argument on social media in 2021 – amongst ‘the medical men of all nations for the purpose of injuring mankind at large’. Despite the enmity Playfair stood firm in his Memoirs saying that ‘these attacks pleased them but did not hurt or even annoy me’.

Playfair’s intervention was to delay rather than defeat the League and his opponents were to prove adept at making vaccines a ‘test question’ for all Parliamentary candidates, the classic tactic of making it an issue that will not go away.

In 1885, a massive anti-vaccination protest in Leicester attracted a crowd of nearly 100,000 people. In response, a Royal Commission was formed to understand attitudes on all sides regarding vaccination. Their report in 1896 stated that vaccination was effective in protecting against smallpox, but it also recommended that the government abolish the penalties for not vaccinating.

Ironically, a serious smallpox outbreak in Gloucester that year proved the scientific logic of Playfair’s argument, but by then the momentum was against him. A large percentage of the population was unvaccinated and more than 2,000 people fell ill; and the suffering of the city’s children was recorded in poignant photographs.

In 1898, a new Vaccination Act removed these penalties and introduced the ‘conscientious objector’ clause that allowed parents who did not believe vaccines were safe or effective to obtain a certificate exempting their children from vaccination.

The vaccination regime that Playfair knew was rather rough and ready compared to the rigorous testing and regulation we enjoy, but it was still highly effective.

Compulsory vaccination for smallpox in the UK ended in 1948, and in 1980 the World Health Organisation announced that the virus had finally been eradicated.

However, smallpox remains the only human disease to have been wiped out. Infectious diseases, pandemics, and the vaccination debate, are firmly here to stay.

My thanks to colleagues Roger Highfield (Science Director), Natasha McEnroe (Keeper of Medicine) and Stewart Emmens (Curator of Community Health) for their advice and comments on this blog; and to Katie Dowler for her research support.