As the seat of royal power in 17th- and 18th-century France, Versailles was renowned for its opulent palace and gardens. But it was also a place of serious – and often groundbreaking – scientific enquiry and experiment. From new medical procedures to the first hot-air balloon flights, this trail invites you to take a look at objects and stories in our permanent galleries inspired by our Versailles: Science and Splendour exhibition (open 12 December 2024 – 21 April 2025).

STOP 1 – MEDICINE: THE WELLCOME GALLERIES

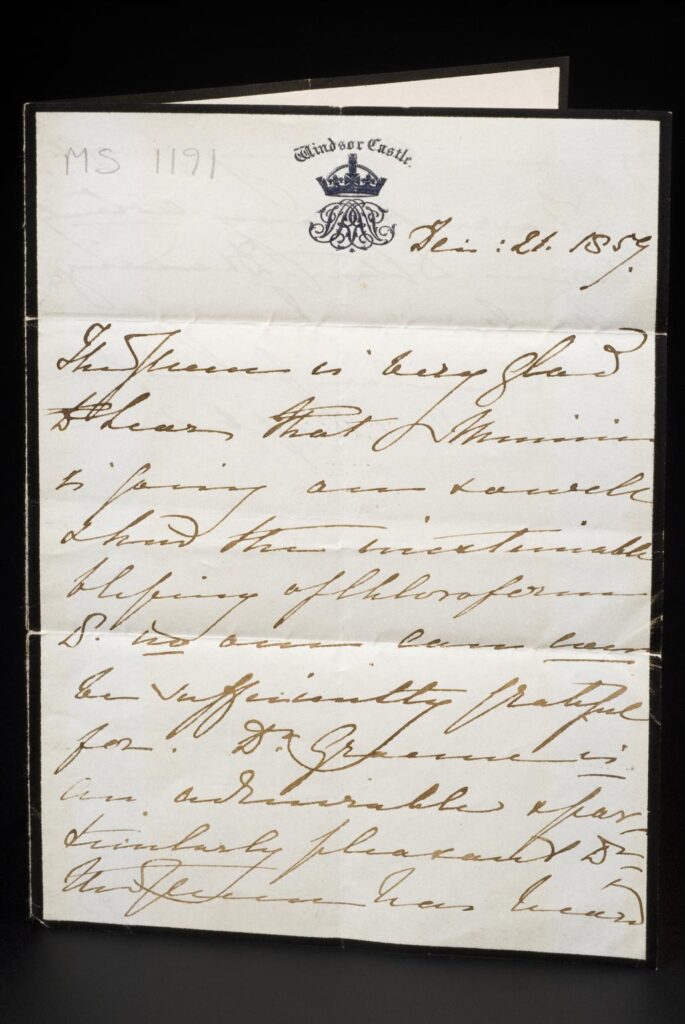

Start your tour by heading to the Medicine galleries on level 1 of the museum. Take Lift or Stairs C (right before Exploring Space) and head into the Medicine galleries. Cross the rooms of ‘Medicine and Bodies’ and ‘Exploring Medicine’, and turn left into ‘Medicine and Treatments’. The first stop is Object 9 in the Surgery and Innovation display, a letter written by Queen Victoria. She persuaded many women that chloroform, an anaesthetic gas, was safe for use in childbirth. It was administered to her during her pregnancies, and she wrote enthusiastically about it in her journal, and in the letter on display here. Dated from December 1859, she writes about ‘the inestimable blessing of chloroform which no one can ever be sufficiently grateful for’.

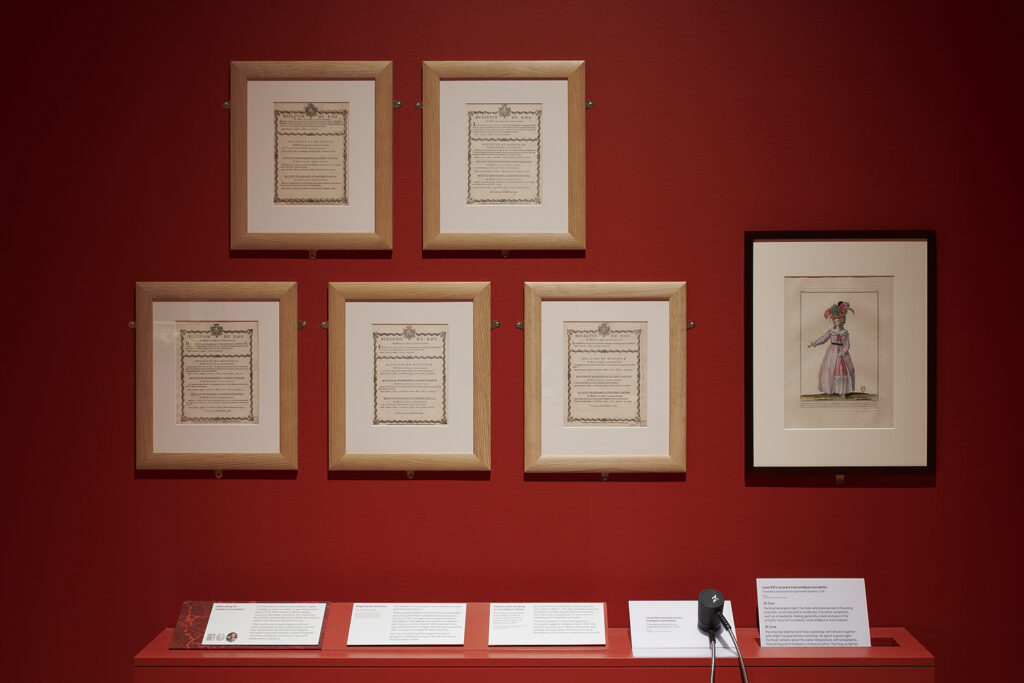

On the other side of the Channel a century before, another monarch had been an advocate for a medical procedure recently introduced in Europe. Shortly after King Louis XVI ascended the French throne in 1774, he and several close family members were inoculated against smallpox – a contagious disease which had killed his predecessor Louis XV a few weeks before. At the time in France, smallpox inoculation was viewed with suspicion: the king subjecting himself to this procedure was a matter of national interest, and a great encouragement for his subjects to follow suit.

STOP 2 – INFORMATION AGE

Go back towards ‘Exploring Medicine’ and take Lift or Stairs D up to level 2. Turn right and head into the Information Age gallery. Inside, look for the ‘Cable’ section on the left, where you will find the Mechanical puppet theatre. Watch this puppet show which tells the story of how the electric telegraph was invented, and which shows a peculiar experiment by Abbé Nollet.

In 1746, French scientist Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet gathered a group of monks into a large circle. The monks held metal wires in their hands, creating a long connected chain. When Nollet discharged static electricity through the first monk of the chain using an early form of home-made battery, he was hoping to measure the speed of electricity as it travelled through the circle: the monks’ muscles would contract from the electric shock. Unfortunately for Nollet (and for the monks!), electricity travels at such a speed that all the monks were shocked almost instantly.

Nollet later recreated this experiment with soldiers in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. His public demonstrations of scientific principles ‘to make the invisible visible’ contributed to the popularisation of science at court. On display in the Versailles exhibition is his air pump, which he used to demonstrate the properties of air and the effects of air pressure to the royal children at Versailles.

STOP 3 – MATHEMATICS: THE WINTON GALLERY

Head out of the gallery via the same entrance you took, and walk past the lift and stairs to head into Mathematics: The Winton Gallery on the same level. Cross the gallery, and right before you reach the exit, turn left into the ‘Perspective’ section to find the next stop: a print of Herrenhausen Gardens.

Mathematics played an important role in creating formal European gardens. This print shows mathematical principles in the garden design for Herrenhausen Palace (a royal residence in Hanover, now part of Germany). The use of perspective places the visitor’s gaze at the centre of the landscape, with ordered, geometric layouts implying power over nature itself.

While Herrenhausen’s gardens were being developed, King Louis XIV was transforming those at Versailles using similar mathematical techniques. As the Versailles exhibition shows, from the 1660s, surveyors used precision instruments to level and landscape the marshy terrain, creating vast perspectives and geometric patterns. Versailles’s gardens became some of the most spectacular in Europe, and symbolic of the king’s power in their scale and regimented structure.

STOP 4 – SCIENCE CITY 1550 – 1800: THE LINBURY GALLERY

Exit the Mathematics gallery and head straight into Science City. Pass the first section ‘A New Trade in London’, and turn left to find the Royal Society diorama.

The Royal Society of London was founded in 1660 to bring together leading scientific minds of the day, and it became an international network for practical and philosophical investigation of the physical world. The members, called ‘Fellows’, regularly met to observe and discuss experiments. In this diorama scene, an air pump – similar to the one later used by Abbé Nollet at Versailles – is being prepared for an experiment. Air would be removed from the pump’s sealed glass chamber to observe, time, and record the effects on objects placed inside.

A few years after his British counterparts, in 1666, King Louis XIV had the Royal Academy of Sciences created in France. His goal was to attract some of the best and brightest scientific minds in Europe to work directly for the French state and enhance France’s scientific reputation. Some Academicians were also enlisted in the building of the Palace of Versailles, and collaborated and competed with members of the Royal Society on different scientific projects and challenges. Both the Royal Society and the Academy of Sciences still exist today.

STOP 5 – THE CLOCKMAKERS’ MUSEUM

Head to the opposite side of level 2 into the Clockmakers’ Museum, and walk down the gallery until you reach Display X: ‘John Harrison (1693 – 1776), The Challenge of Longitude’.

In the 18th century, sailors had no accurate means of finding their longitude (east-west position) at sea. Accurate time-keeping was vital for solving this issue, so scientists across Europe were urged to create a reliable marine clock to make navigational mapping and wayfinding more precise, and trips safer. The quest was of such importance that in 1714, the British government offered a prize of £20,000 for a solution (about £314.3m in 2024). John Harrison eventually won that prize with his revolutionary timekeeper H4, very similar to his H5 on display here.

Want to know more about the rival French quest for longitude in this period? Curator Richard Dunn takes a closer look at a sea clock on display in Versailles: Science and Splendour, and at British and French game-changing navigational innovations in this blog post.

STOP 6 – FLIGHT

Continue walking through the Clockmakers’ Museum, and take the lift or stairs up to level 3, and head to the Flight gallery. At the entrance, you will find the model of the Montgolfier hot-air balloon.

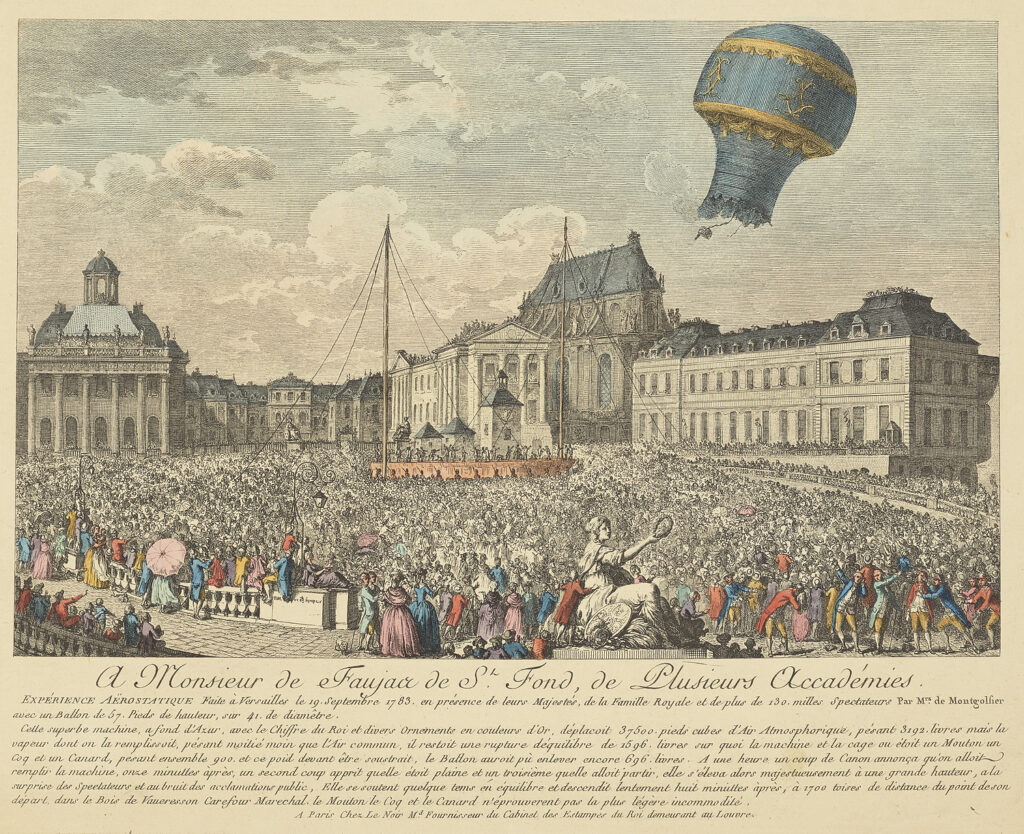

In September 1783, King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette and 130,000 spectators watched in awe as a hot-air balloon took flight from Versailles. Carrying a sheep, a duck and a cockerel in a wicker basket, it was the first ever flight with living passengers – who all made it back to the ground safely. The experiment was carried out by the Montgolfier brothers, pioneers in hot-air ballooning.

A few weeks after their test in front of the court, the brothers repeated their demonstration at another royal palace near Paris, but this time with human beings for the first time in history. This model is a small-scale reproduction of the hot-air balloon used during this historic feat, which began the history of manned flight. Like the balloon flown at Versailles shortly before, it is decorated with intertwined letter ‘Ls’ in honour of King Louis XVI.

Keen to find out more? Explore more blog posts about our Versailles: Science and Splendour exhibition.