As the curator of the museum’s Science Fiction exhibition, it will come as no surprise that I am a strong proponent of the idea that science is an important and fruitful stimulant of our creative imagination. A recent publication captures the truth of that idea by using the work of CERN as its imaginative fuel.

Collision: Stories from the Science of CERN, is a collection of thirteen short stories inspired by one of the most ambitious scientific experiments in human history – the vast complex of the Large Hadron Collider which lies a hundred metres below the French-Swiss border and seeks to answer some of the most mind-bending questions in physics.

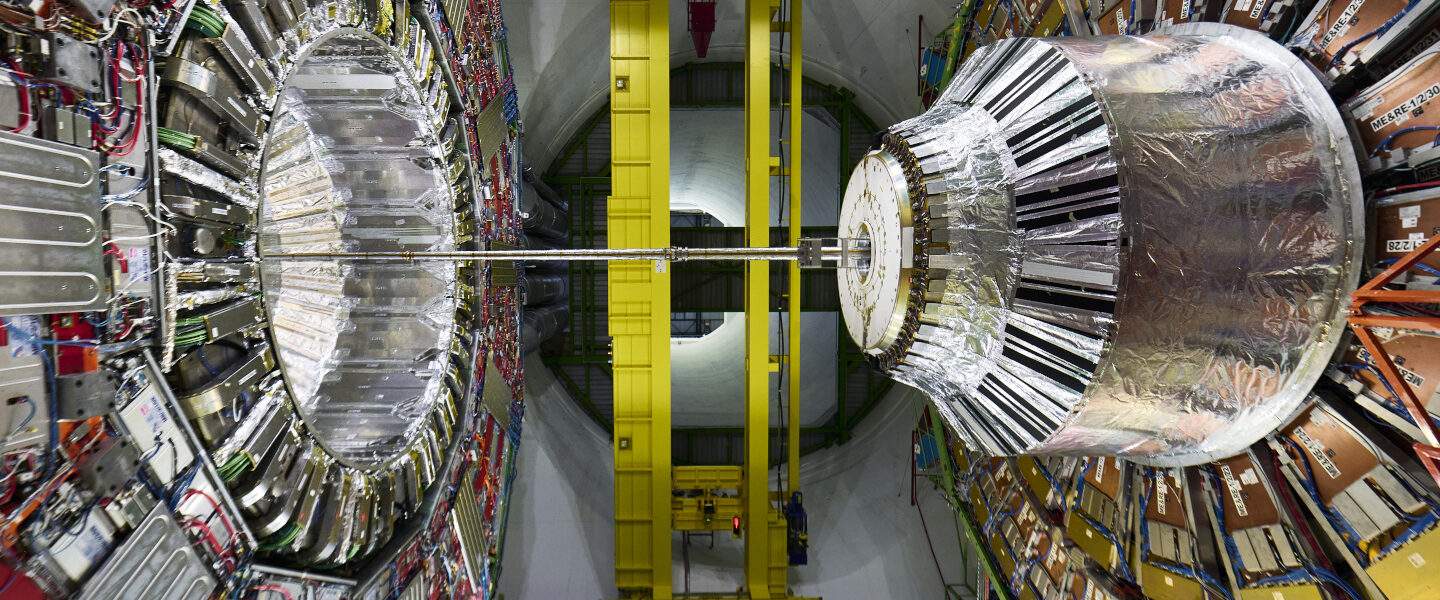

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a fascinating piece of equipment in and of itself, which is one of the reasons we created an exhibition about it in 2013, Collider, which used immersive techniques of theatre, sound and video to wow visitors with the sense of awe created by this 27-km long particle collider and its cathedral-sized detector caverns.

Dr. Harry Cliff, the curator of that exhibition, explained this approach to me: ‘The LHC is a scientific project on an epic scale, both the enormous size of the machinery and the global team of scientists and engineers who make it work. With Collider we really wanted to give visitors the feel of a visit to CERN, which is why we worked with a team from theatre to help recreate this extraordinary place at the Science Museum’.

One of the striking things about Collision is the variety of writers on display, from former Doctor Who and Sherlock showrunner Steven Moffat with his first ever piece of prose fiction writing, to broadcaster and journalist Bidisha Mamata and literary biographer and novelist Dame Margaret Drabble, via science fiction greats such as Stephen Baxter and Ian Watson.

Each of the thirteen writers made a visit to the CERN facilities to jumpstart their imagination, and spoke with some of the thousands of scientists whose work involves the facility. Each of their stories is followed by an essay by one of these scientists which explains the factual underpinning to the fiction, and uses the story to further unpack their research and discoveries.

This collaborative approach to storytelling is fitting, given that CERN is one of the largest collaborative scientific endeavours in the world. The first scientific paper to be published about the LHC’s discover of the Higgs Boson particle, for example, featured 5154 named co-authors: 24 of its 33 pages were needed just to list their names and institutions!

There is something dizzying about CERN, a sort of intellectual vertigo one feels when you look from the vast size of the LHC and the legions of scientists, technicians, and other professionals required to maintain it and run experiments, and then realise that they are looking for particles smaller than atoms which are exposed in the brief violent smashes as high-energy particle beams collide at almost the speed of light. Narrative fiction can provide helpful handholds to steady a reader, a human-scale narrative that exists between these extremes.

Ian Watson’s story “Skipping” is a great example of a science fiction story giving shape to an abstract concept of theoretical physics. Set in an unspecified future century, the trillions of dollars spent on a CERNPLUS facility have finally yielded the discovery of gravitons, and the subsequent invention of graviton beams which allow space ships to ‘skip’ through the higher dimensions of the galaxy and travel to distant stars faster than the speed of light.

Watson’s tale impresses upon the reader the significance of physics so far beyond our knowledge that it collapses the boundary between science fact and fiction. ‘We don’t actually know if the graviton even exists’, writes Dr Andrea Bersani in his afterword to Watson’s story, let alone the possibility of creating graviton beams, he explains the appeal of a story like “Skipping”: ‘even though, as a physicist, the idea of it strikes me as just a pipe dream, and all current knowledge suggests this will never be possible, as a human, I have to believe I might be wrong.’ This is the appeal of science fiction, to challenge the limits of scientific certainty.

Not all of the stories presented in Collision are science fiction however, underlining the point that scientific material can be inspiration for storytelling in any genre. Lucy Caldwell’s “Dark Matters”, for example, centres on a particle physicist working on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) Experiment at CERN. The protagonist is able to explain to layman family members about their work, and in doing so offer the reader insights into dark matter, quantum, and particle physics.

At the same time, as Dr Joe Haley notes in his accompanying essay, this is a story about uncertainty. Uncertainty in respect to science: as Haley explains ‘the general principle that most answers just lead to even more questions highlights a common, and somewhat oxymoronic, feature of the scientific endeavour: that we can know so much about something and yet so little at the same time.’ But there is also a human level to uncertainty: The protagonist of Caldwell’s story has returned home to Belfast to spend time with a dying parent and so the story becomes one also about the uncertainty of futures and families, health and mortality. With references to lockdown, it folds in the uncertainty felt at the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic, and reminds us that behind the scientific brilliance are human beings with human problems. It’s a brilliant story which reminds us that physics research is a multigenerational endeavour that transcends a human life.

Collision is an entertaining and mind-expanding book, but it’s also a great example of the implicit conversation between science and fiction made explicit. It demonstrates how fiction can take the work of science at its most cutting edge and help it to excite and entertain, putting a human face to both the vast apparatus and experiments of facilities like the LHC, as well as the infinitesimally minute subatomic particles they study.

Keen to hear more about Collision: Stories from the Science of CERN? Book free tickets for Science Fiction Lates on Thursday 4 May to hear authors Steven Moffat, Bidisha Mamata and Adam Marek read their short stories from the book.

Don’t forget! Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of Imagination is at the Science Museum until 20 August 2023. Book your tickets now