At the start of the First World War many people harboured the view that war was ‘man’s business’. Front-line roles had, after all, always been undertaken by men.

Between 1914 and 1918 opinion changed when women – invigorated by years of struggle for female emancipation – stepped out from their traditional roles and placed themselves at the heart of the action.

Taking on key medical roles, they emerged from the conflict with newfound respect and observers heralded the war as ‘a revelation of woman’.

Trained nurses had been part of the military establishment since the 19th century. Thousands of untrained women now stepped forward to help support the care of the wounded.

Within the Wounded exhibition we hear the voice of Sophie Hoerner, who was stationed at No. 1 Canadian general hospital near Étaples. She paints a vivid picture of the scale and severity of the task faced by nurses as they cared for the wounded at the Western Front.

In a letter home she wrote:

‘No one could imagine the horrors of a war like this unless they are here and could see for themselves. I have never seen such awful wounds.’

The job of the war nurse was both varied and hectic. Some administered pain relief and redressed wounds. Others assisted the surgical teams in the operating theatres of casualty clearing stations, acting as anaesthetists or carrying out minor procedures when surgeons were rushed off their feet.

Female surgeons found it far harder to offer their services. The army was initially reluctant to make use of their skills, telling them ‘to go home and sit still’.

Undeterred, they set up voluntary hospitals on the Western and Eastern fronts – many staffed exclusively by women. One such volunteer was Dr Phoebe Chapple, who became one of the first at the front line and the first to be awarded a medal for gallantry.

On 29 May 1918, while she was visiting the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps near Abbeville, the camp came under enemy attack. One bomb hit a trench where 40 staff had taken cover. In near darkness and with further risk of attack, Chapple worked her way along the trench, tending to the wounded.

Women also provided a vital link between the battlefield and medical units. The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) ran field hospitals and drove ambulances, often in extremely dangerous conditions.

Pat Waddell, an accomplished violinist, acted as an ambulance driver from 1916 onwards, having learned to drive in London by cajoling taxi drivers to let her take control of their vehicles. The FANYs challenged the traditional view of women drivers. One sergeant wrote:

‘When the cars are full of wounded no-one could be more patient, gentle or considerate, but when the cars are empty they drive like bats out of hell.’

Mairi Chisholm and Elsie Knocker travelled to Belgium as part of the Munro Ambulance Corps designed to support the Belgian Red Cross and transport the injured to hospitals away from the battlefield. They quickly decided that they could be of greater help to the wounded by treating them closer to the front line.

They set up their own dressing station in Pervyse near Ypres – only 90 metres from the action. Earning 17 medals for their bravery they became celebrated in the press as the ‘Angels’ of Pervyse, having saved hundreds of soldiers’ lives.

© Illustrated London News Ltd

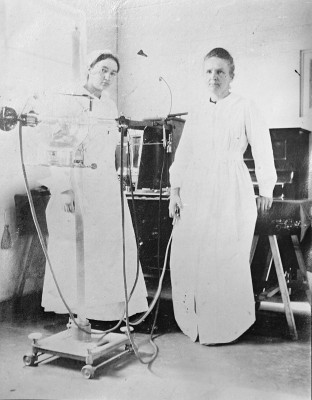

© Musée Curie (ACJC collection).

Perhaps the most famous woman to work at the front line was Marie Curie. By the time war broke out she was already a double Nobel prizewinner – one for physics (the first Nobel Prize to be awarded to a women), the other for chemistry.

Curie was shocked to see how soldiers’ lives were being lost because they had to be transported long distances for examination.

So she set about bringing diagnostic equipment to the battlefield.

Twenty vehicles were fitted out with X-ray units, darkrooms and technical personnel. Curie learned to drive so she could operate one of the mobile cars herself.

She also set up 200 stationary X-ray stations, helping train 150 women as radiology technicians to help run them.

Over 1 million wounded soldiers were examined thanks to her efforts, with Curie herself declaring:

‘The use of X-rays during the war saved the lives of many wounded men and saved many more from long suffering and lasting infirmity.’

Women’s front-line activity did not end there.

They acted in many other important roles, from telegraphist and cook to war correspondent and spy. Added to the vital work being carried out by female workers back at home, these varied roles show that the First World War was not just a conflict that made heroes, but many heroines as well.