On 6 March 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table was announced to the Russian Chemical Society.

Although it looks different from its modern form, it demonstrates Mendeleev’s key insight – the periodic law. In his own words:

If all the elements are arranged in the order of their atomic weights, a periodic repetition of properties is obtained. This is … the law of periodicity.

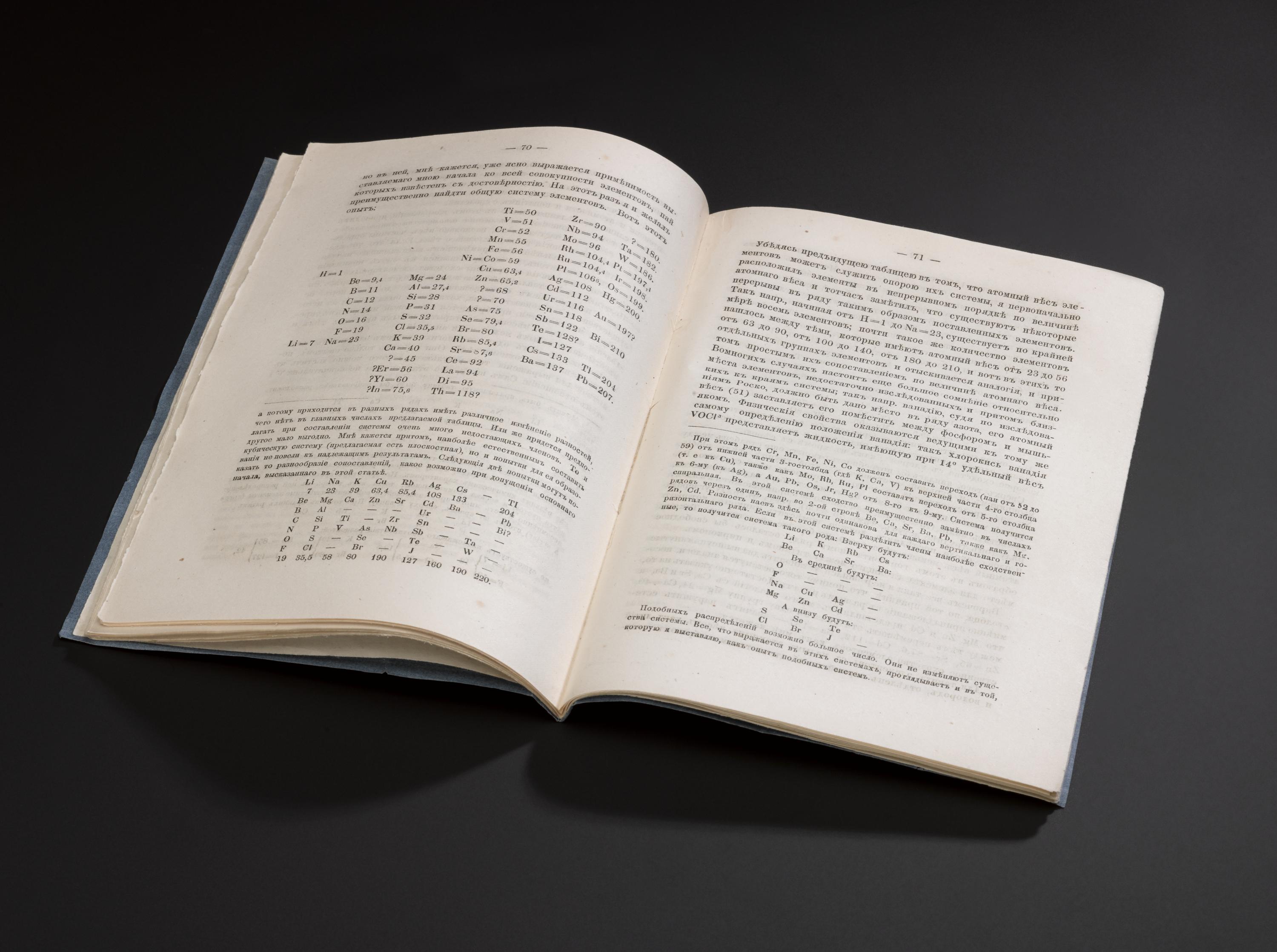

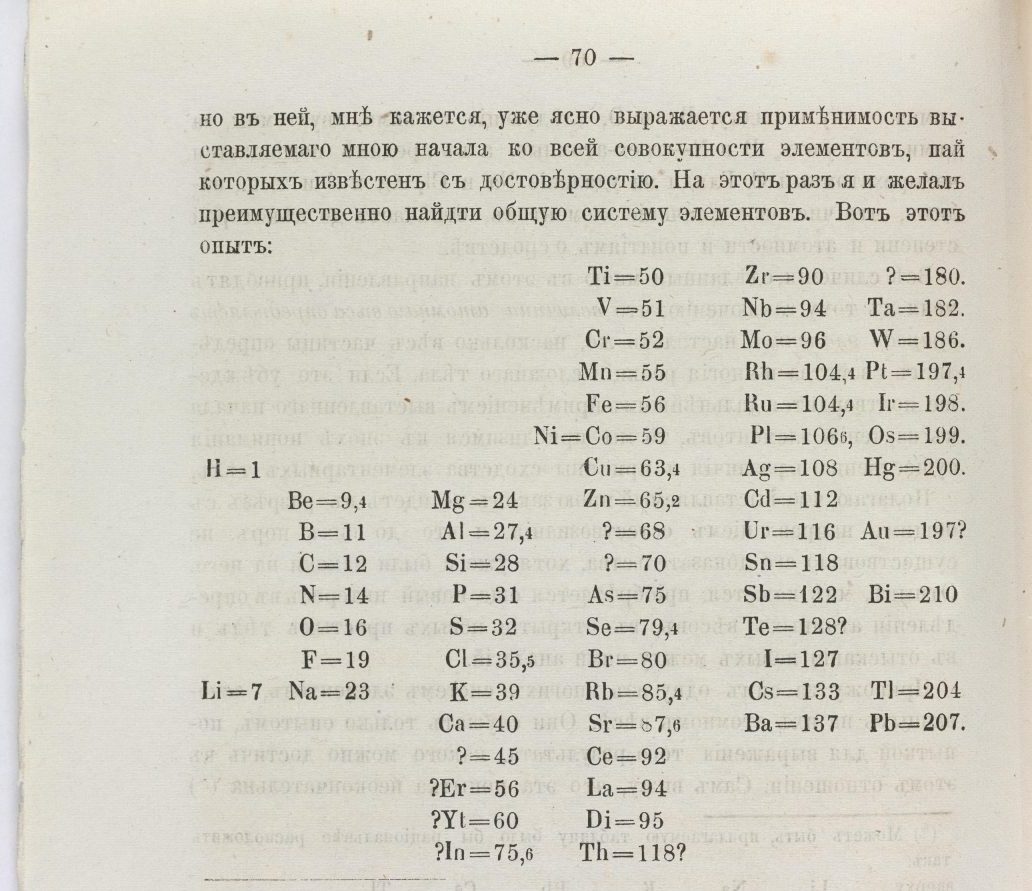

Our new display includes an 1869 print of the journal containing Mendeleev’s first published periodic table. This is the first time the print has gone on display at the museum since it joined the Science Museum Group Collection in 1980.

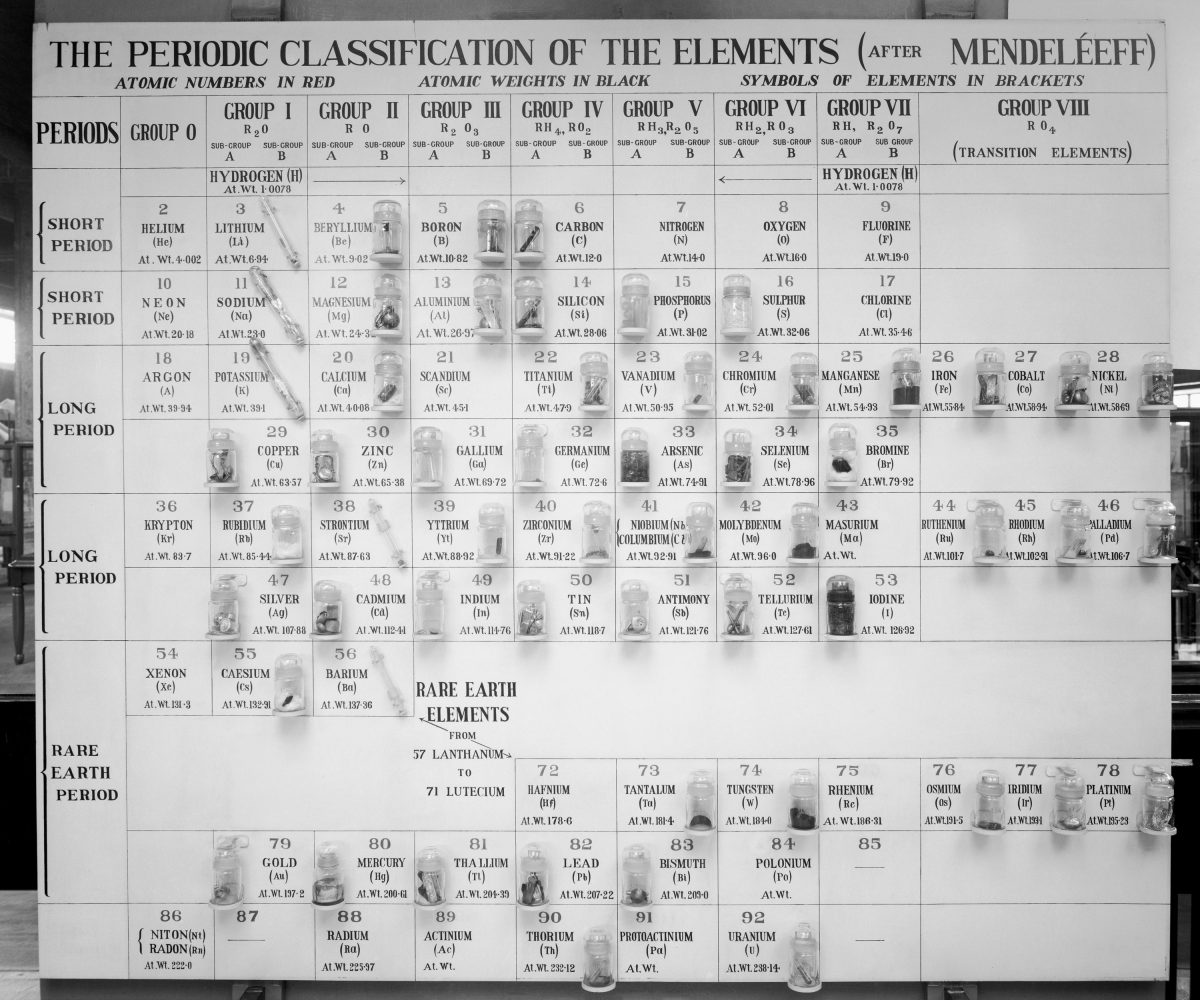

This early attempt looks unlike the modern form of the periodic table, as the chemical symbols for the elements are arranged by weight downwards rather than across.

In the table on display you can see the gaps Mendeleev left for elements yet-to-be-discovered, where he placed a question mark and a predicted weight.

These gaps were one of the reasons Mendeleev and his table became internationally famous, as three of his predictions were vindicated when the elements were discovered – gallium in 1875, scandium in 1879, and germanium 1886.

While not the first to put forward a periodic table, it was his that endured, forming the basis of the one we know today, as it evolved over the next 150 years.

Mendeleev conceived of his system to classify the elements at a time when only 60 or so chemical elements were known – about half of today’s count.

Just twenty years after Mendeleev published his periodic table, French politician and linguist Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte had amassed a collection of the then-known elements. If his surname seems familiar, it is because he’s better known as Napoleon’s nephew.

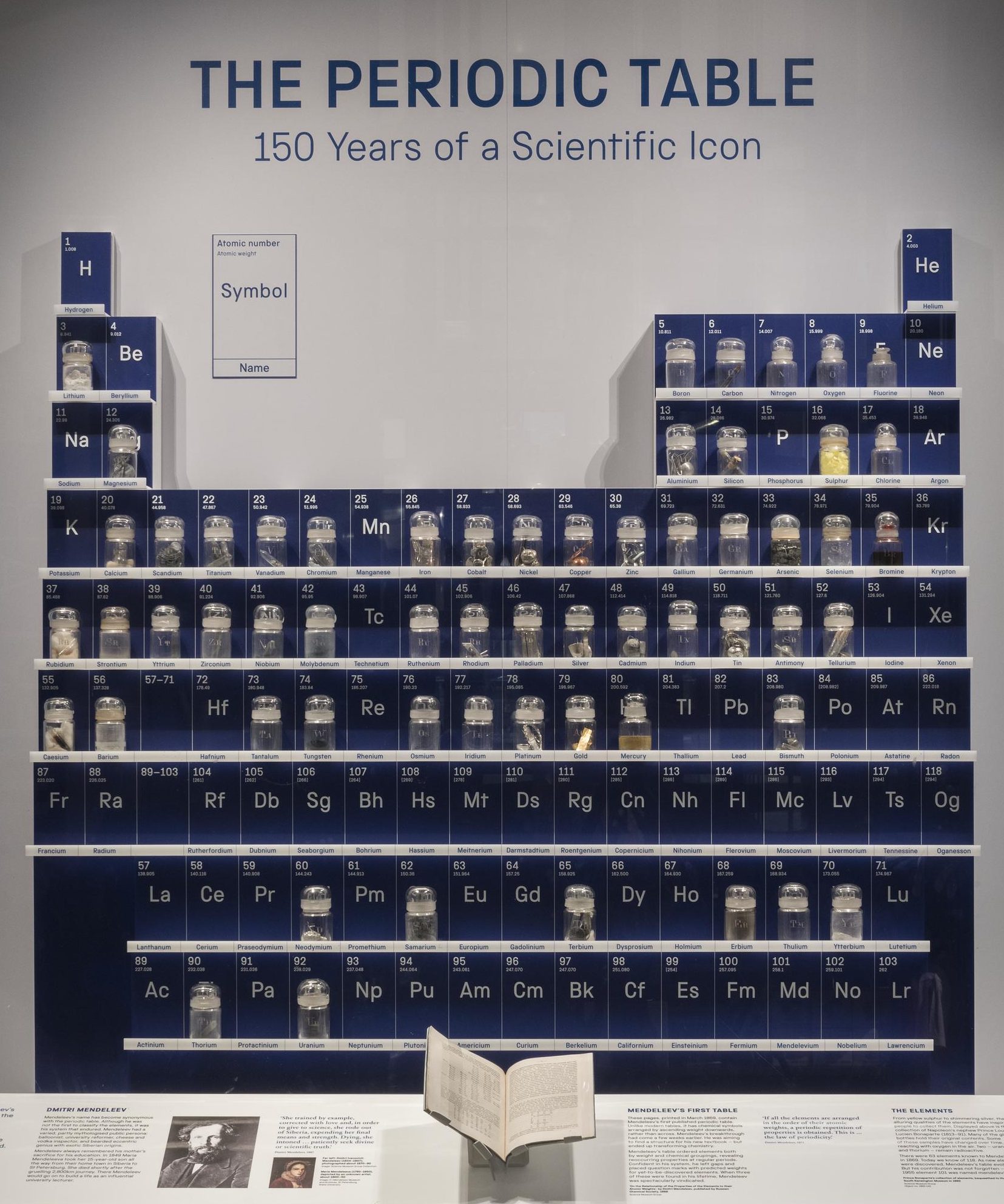

Prince Louis was probably one of the first to collect elements as a hobby, and over 50 of his elements are included in our new display.

From shimmering silver to radioactive uranium, Prince Louis collected as many of the known elements as he could and bottled them in purpose-made glass jars, etched with their corresponding chemical symbol.

Many of the elements are original samples acquired by Prince Louis, though some have altered over time, reacting with the oxygen in the air. Mercury, once a silvery liquid, has become the yellowish-brown coloured mercury oxide. It is the same oxidation process which causes iron to rust.

Prince Louis was likely inspired by Mendeleev, wishing to possess all the basic ingredients of matter that Mendeleev’s table classified.

He bequeathed his collection of elements to the South Kensington Museum, the predecessor of the Science Museum and V&A, in 1892. His decision to make this gift was based on a visit he made to the museum in 1890 to view its metallurgical specimens.

They were first exhibited in 1906, three years before the Science Museum came into official existence. Twenty years later, these elements formed the centrepiece of a chemistry gallery in a periodic table display.

This remained in place for decades. The neurologist and author Oliver Sacks recounts his visits as a child in his memoirs Uncle Tungsten:

‘seeing the table .. altered my life. I took to visiting it as often as I could. … It was like a garden … the enchanted garden of Mendeleev’

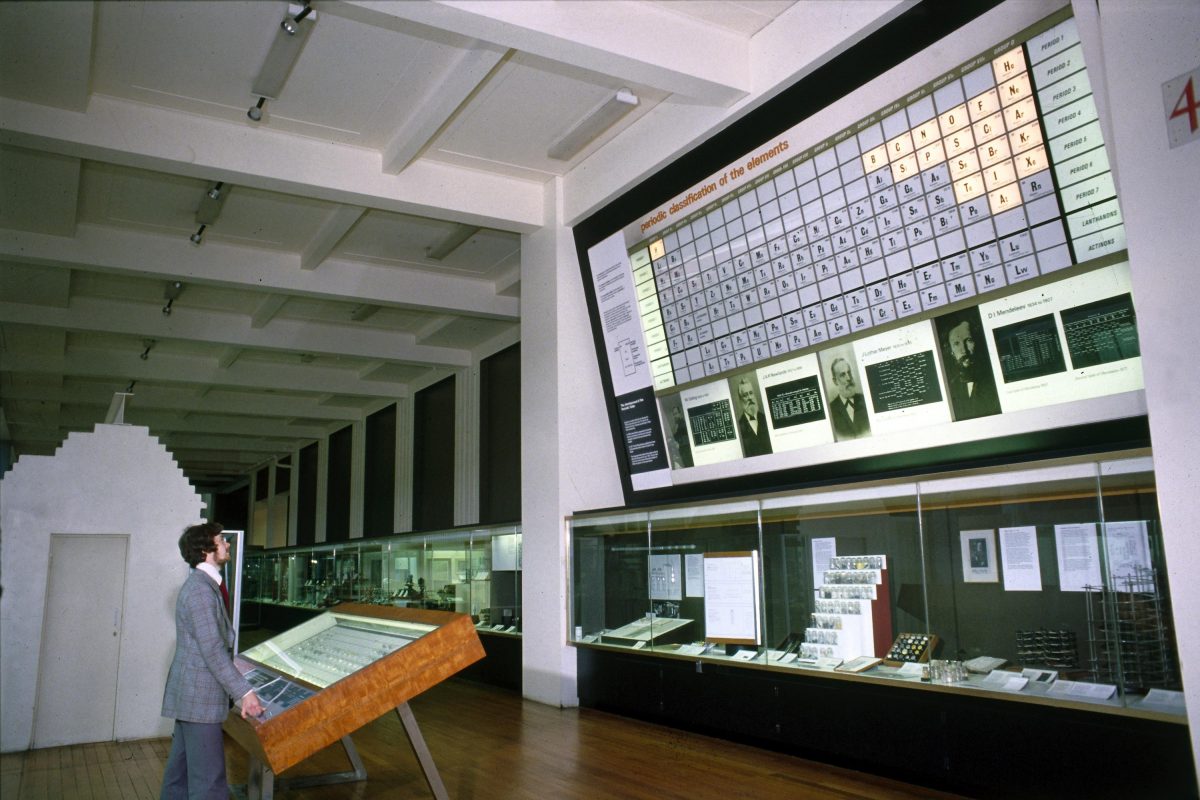

The Science Museum’s last periodic table display opened in 1964, featuring a giant interactive table. The Bonaparte elements shifted from the centrepiece to an accompanying showcase.

The Bonaparte elements are now back on public display after a 30-year absence, arranged according to the present form of the periodic table which is familiar to many.

Perhaps they might enchant a new generation with their alluring materiality and the simplicity of the system that classifies them.

The Science Museum is celebrating the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements by hosting ChemFest 2019, a festival of chemistry organised in partnership with cultural institutions across South Kensington.

We are interested in collecting items related to the International Year of the Periodic Table (from home-made periodic tables to printed ephemera), preserving these as part of the collection to record worldwide celebrations in 2019.

Delve into interesting stories of how chemistry affects the world around you in our online series.