Fifty years after it was released, why is it so important to see it on the big screen? And can cinema still be a transcendental experience? Paul Franklin, director and Academy-Award winning visual effects designer (Inception, Interstellar) talks about his fascination for Kubrick’s sci-fi classic and highlights the joys of watching an ‘unrestored’ print.

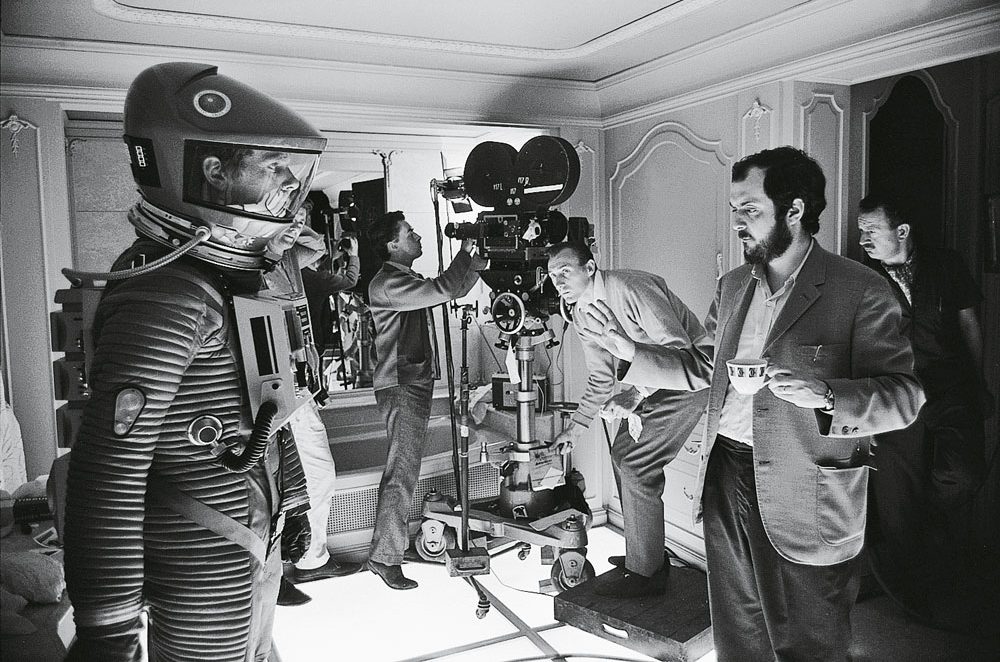

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey has long been held as a gold standard for cinematic image quality, filmed using the high-resolution Super Panavision 70 system and exhibiting all of the hallmarks of Kubrick’s meticulous working process. I first saw 2001 when I was about ten years old, and it was a key experience that helped to set me on the path to becoming a film visual effects designer.

However, like many who grew up in the 70s and 80s Kubrick’s original 70mm vision wasn’t available to me – during that period only those lucky enough to live in big cities with a surfeit of cinemas had that privilege – instead I saw it on television, broadcast by the BBC in blurry 625 line PAL on my parents’ 25 inch colour TV (roughly 1/4 the resolution of a modern HD TV) which gave an “impressionistic” rendering of the film, to say the least.

Over the years the presentation of the film gradually improved – VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, various restorations – and now, after 50 years, we’re finally back to something close to the way it looked in April 1968 when the film was first released. But why get excited about a photochemical print of a half-century old film? Surely the advances in digital projection have far surpassed anything that Kubrick could have achieved in the 1960s.

Well, it is true that many old films have benefited from digital restoration, cleaning off the dirt and scratches that have built up over the years and bringing back some of the vivid clarity of their original colours, but the fact remains that even the sharpest 4K digital projection only captures about 25% of the resolution of the original 70mm print and, regardless of what the sales people in the TV show room may tell you, there are some colours that just don’t translate from film to digital. 2001: A Space Odyssey, Unrestored has the scratches and glitches of a hand-crafted artefact, but it has so much more that all digital “approximations” of the film have lost over the years.

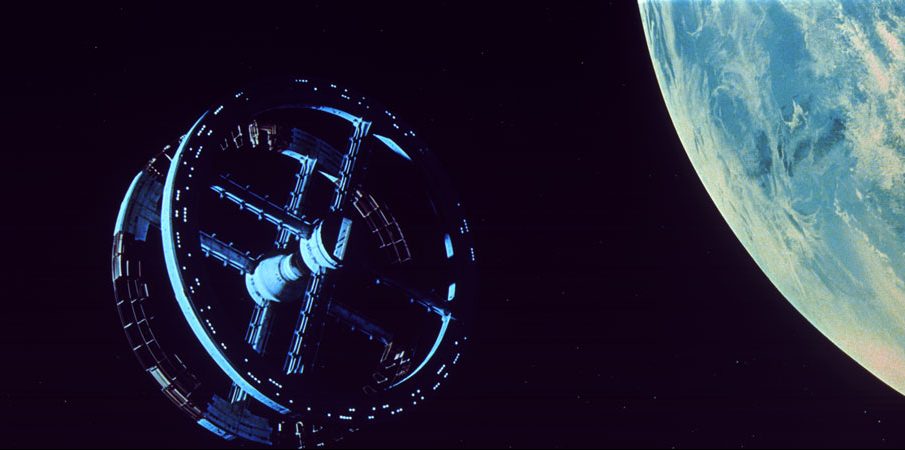

2001: A Space Odyssey is where the modern science fiction aesthetic – so successfully adopted by Star Wars a decade later – really begins. Kubrick rejected cinema’s previous fantasy-based efforts to represent space travel, turning instead to NASA and the rapidly developing world of high-tech industry to create a compelling future that is as much concerned about the small details, such as the Pan Am logo on the tail of the shuttle, as it is about the grand scale of the solar system and the machines that transport our heroes across it.

Rather like the Apollo Moon missions themselves, 2001 seemingly fell out of the future, fully formed, into the late 1960s. Cinema audiences had never seen anything like it before and not all the initial reactions were good with many people famously walking out of the film’s premiere during the interval.

But great art – and 2001 is great art, not just another movie – often gets a bumpy ride at the beginning and can sometimes take many years to be accepted for what it actually is. And art, or rather the art world, is where Kubrick found his inspiration for one of the other key components of the film; the representation of the alien and the infinite, embodied in the inscrutable black monolith with its obvious debt to 20th century art such as Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” painting of 1915.

Kubrick relentlessly pushed at the limits of every aspect of his film which in turn inspired his collaborators to astonishing heights – for my money, the dazzlingly abstract “Stargate” sequence, created by legendary effects artist Douglas Trumbull, is the greatest ever piece of visual effects filmmaking which I don’t think will be surpassed (and believe me, I have tried!)

A good 70mm photochemical presentation of 2001 on a really big screen is a revelation and, fortunately for us, the IMAX Theatre at the Science Museum in London has one of the biggest screens anywhere. Some things have dated – women and the rest of the world don’t get much to do in Kubrick’s anglo-centric future – but even for people who have seen the film many times in other formats there is so much to discover and experience for the first time – the film becomes immersive, hypnotic and, ultimately, transcendental.

The death of “traditional” cinema, where people sit in the dark and share an experience of light and sound together, has been predicted many times over the years, but for me the continuing fascination with 2001: A Space Odyssey indicates that this is premature and if you want proof then go and see it at the Science Museum while you can.

Watch the trailer for Paul Franklin’s new short film, The Escape:

THE ESCAPE trailer from Paul Franklin on Vimeo.