The problem of waste disposal is as old as time. Evidence of early waste disposal systems have been uncovered in archaeological sites across the world, including an approximately 5000-year-old drainage system found in the Scottish Orkney islands.

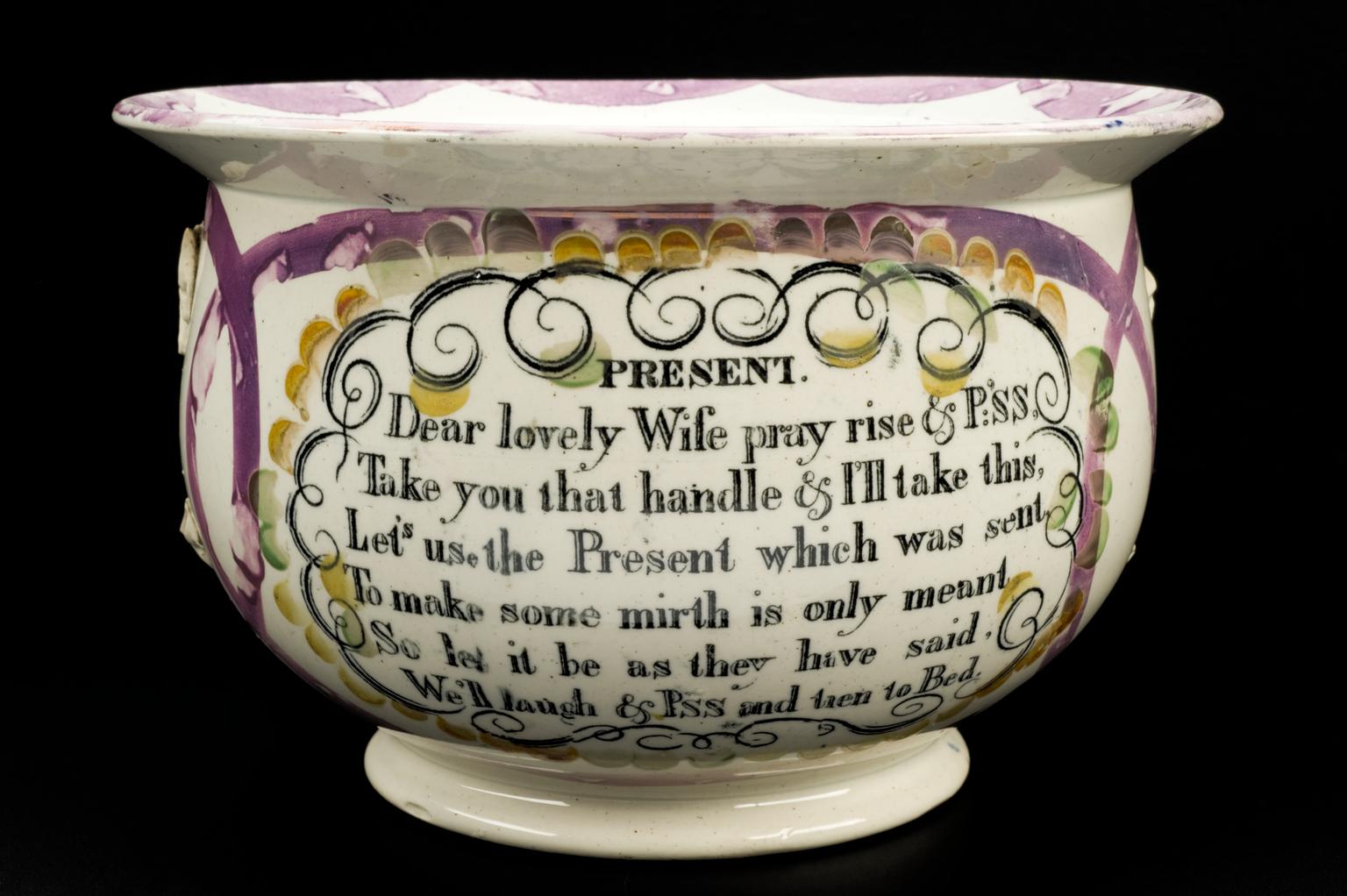

Despite this early evidence, simple chamber pots and cesspits continued to be the most common choice of waste depository until the late 1800s. So doing your business wasn’t the most private or comfortable experience until relatively recently.

Although if you could afford it you could have a very detailed design on your personal chamber pot – and maybe even somebody else to empty it for you!

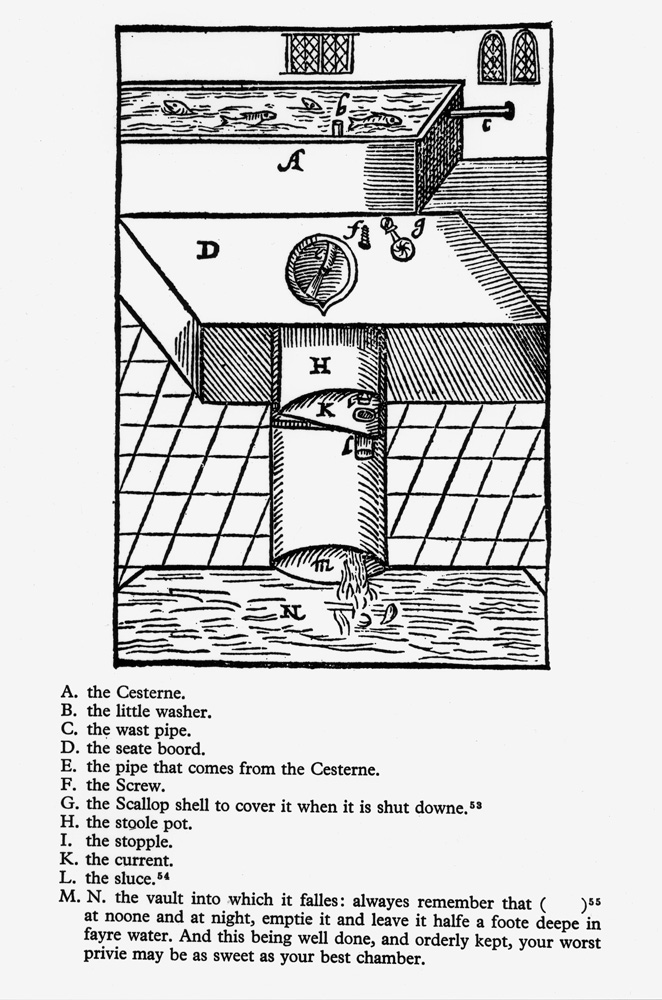

It might surprise you to know that the first flushing loo in Britain dates back to the 1590s.

In 1596 Sir John Harington – Godson of Queen Elizabeth I – published ‘The Metamorphosis of Ajax’ where he described a flushing device which required 7.5 gallons of water to pump waste into the street or water source. He even claimed that it could be used by up to 20 people before flushing!

Harington had one installed at his home in Bath and later installed a working model for the Queen in Richmond Palace, but it clearly didn’t catch on. This could be due to such a huge water requirement in a time before plumbing, as well as the lack of sewers.

It took almost 200 years for Harington’s design to be successfully improved upon.

In 1775, Alexander Cumming – inventor and maker of this stunning clock on display in the museum – was granted the first English patent for a flushing loo.

His innovative addition of a built-in ‘S-pipe’ reduced odours by sealing off the toilet bowl and trapping water in the pipe to prevent any returning smells.

However, the flushing loo still had a long way to go. Whilst Cumming’s S-pipe helped reduce smells, the valves that released water to push out waste still fell short.

One of the most influential improvements was made by inventor and locksmith Joseph Bramah. His design, patented in 1778, improved upon Cumming’s by adding a hinged valve. It became one of the leading designs for the next century.

Until the 1850s, London’s waste removal mainly consisted of cesspits beneath houses or ditches that led waste into the Thames. Many communities outside of London had their own independent drainage systems.

Flushing toilets remained a luxury well into the 20th century, with non-flushing options such as outdoor ‘Earth closets’ especially popular in more rural areas.

This type of toilet was patented in 1860 by Reverend Henry Moule, specifically to provide a more sanitary option for households without indoor piping. It releases clay to cover the waste and is similar to ‘composting’ public toilets often found at festivals and public events today.

Homeowners had been responsible for dealing with their own waste since a ruling of Henry VIII’s in the late 1500s. The British Government’s Public Health Act of 1848 transferred this responsibility into the care of local health boards, enacting that all new homes (and re-builds) should be equipped with a ‘means of drainage’.

This was the beginning of a commitment to centralise responsibility for public sanitation and the first stage in the creation of the sewer systems we so heavily rely on today.

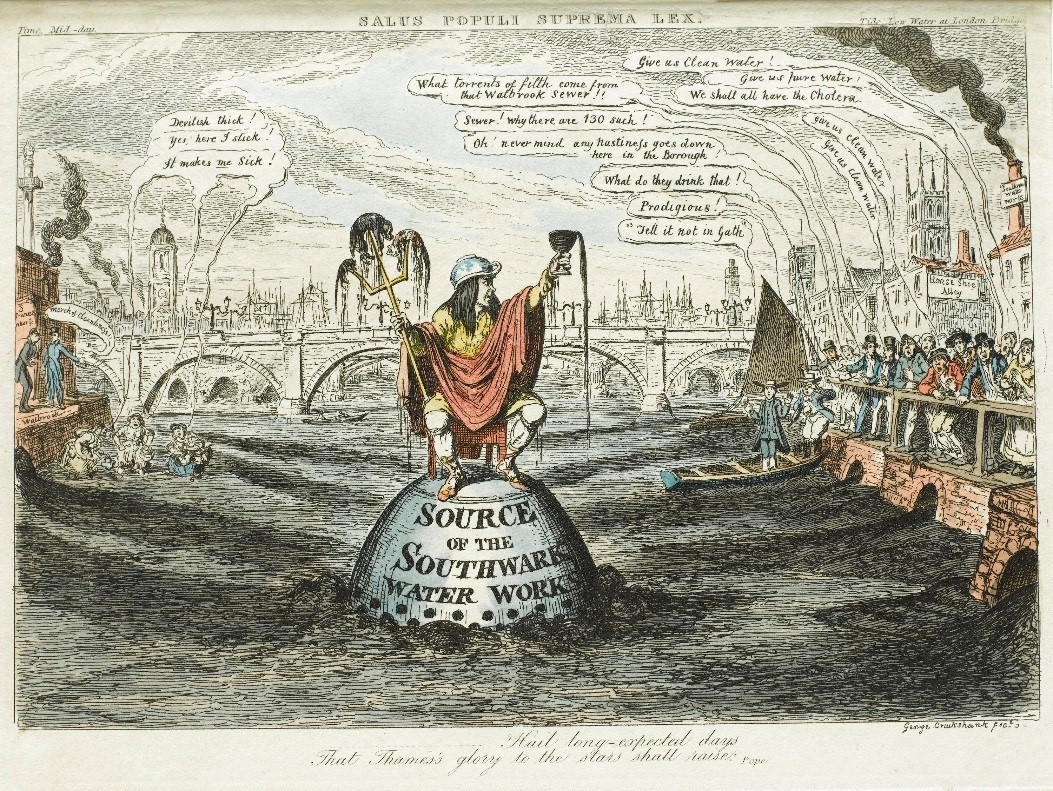

However, the ‘means of drainage’ continued to empty waste into water sources, many of which were used for washing and drinking. This created issues, especially in the increasingly densely populated London, which were compounded with the rising popularity of flushing toilets.

The ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, when the smell got so bad that Parliament closed, and increasing outbreaks of water-borne diseases such as Cholera, forced the British government to act.

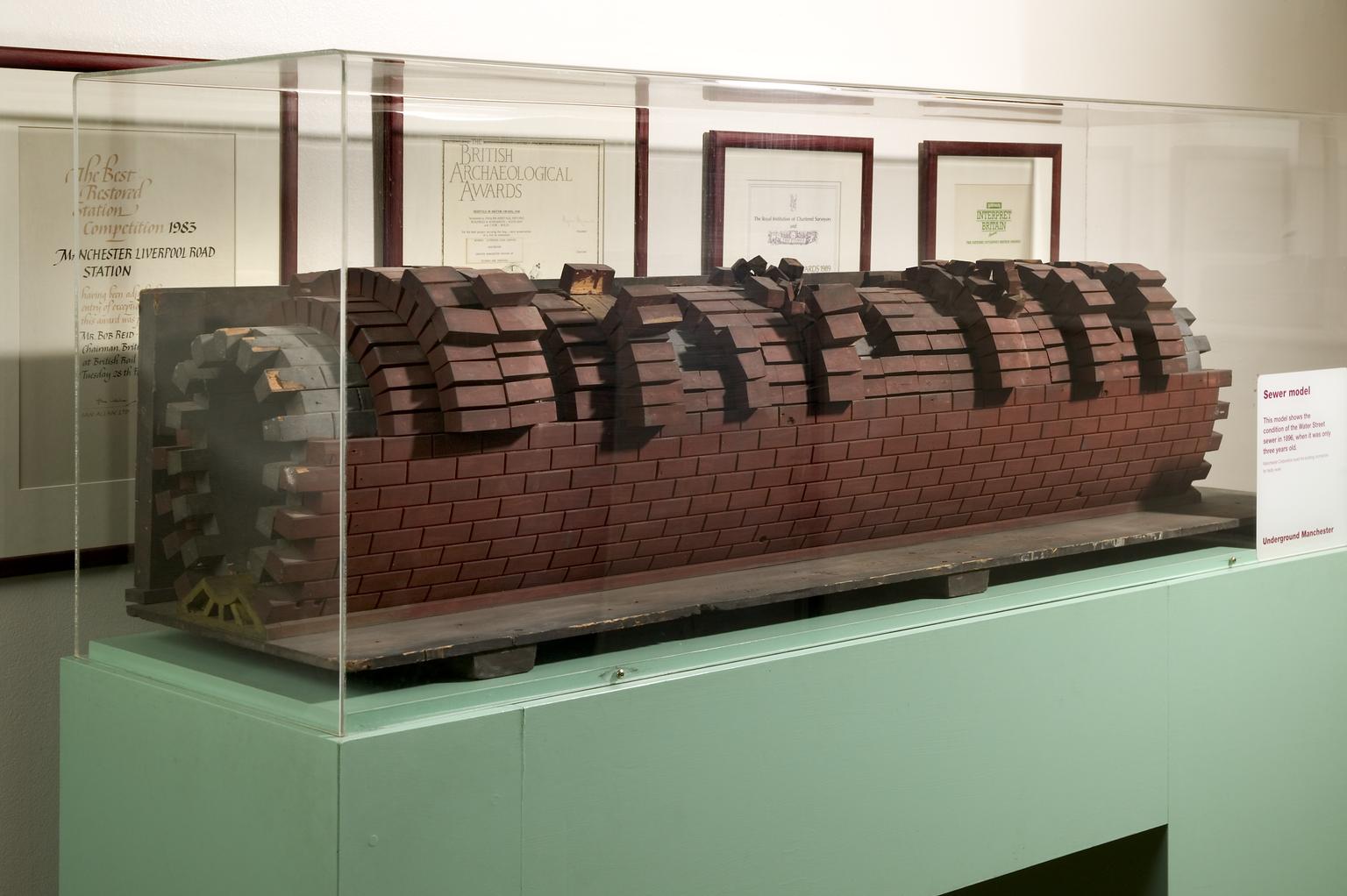

A 16-year sanitation project began very quickly that same year, with railway engineer Joseph Bazalgette at the helm. Over a thousand miles of drainage pipes were installed under the streets of London, feeding into 82 miles of sewers that led to 4 pumping stations across London via 6 ‘interceptor’ sewers.

This huge engineering feat that funnelled waste 8 miles downstream of the city, into the water source of less populated areas. Bazalgette’s brick lined sewers remain the foundation of today’s sewer system.

Right in the midst of this sanitary revolution, J.G. Jennings installed the first flushing public loos – or as he named them, ‘Monkey closets’ at the Great Exhibition. Known as a pioneer of sanitary science, Jennings also contributed to improving the flushing lavatory, patenting improvements to Bramah’s design in 1852 with a wash-out design that remained one of the most popular toilets throughout the century.

By the 1870s, the sanitary business was booming. There were multiple popular toilet designs made by a number of companies across the UK, but they all had limitations.

The wash-out toilet had complaints of noise, an insufficient, often failing flush and a tendency to splatter. Its popularity has been put down to the abundance of patented add-ons and improvements.

In 1870, Stevens Hellyer created the Optimus in an attempt to improve upon some of these complaints by improving the flushing mechanism.

Another innovator of the flushing bog was Thomas Twyford.

Twyford had been in the sanitaryware business since 1849, and his company still exists today as Twyford Bathrooms. During his career he also made improvements to Bramah’s design, as well as created a number of wash-out models, starting with the National in 1871.

In 1883 Twyford made a move away from metal and wood designs towards porcelain with the first one-piece porcelain loo, the Unitas. This design meant that the unit could be kept entirely clean. It also had the selling point of a hinged seat, so it could also function as a male urinal.

Before this, the toilet bowl had been entirely separate and a wooden enclosure was required to provide a seat. This was a direct improvement on Jennings’ wash-out closet, and Twyford continued to refine it throughout his life.

At this point, you may be wondering where Thomas Crapper comes into our story.

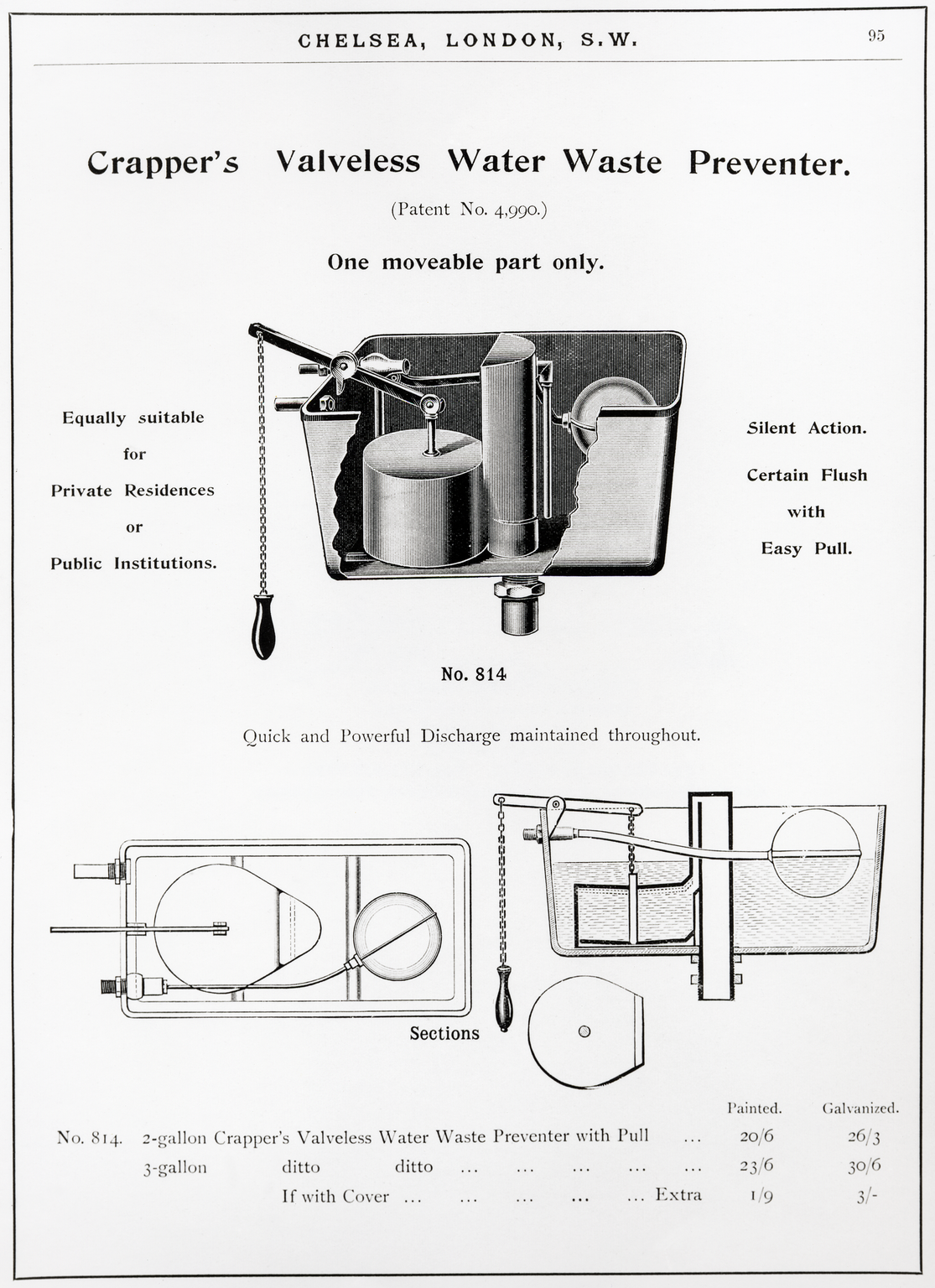

He clearly didn’t invent the toilet and this misconception may be due to his questionable advertising practices, which implied the invention of the Syphonic flush was his own. In fact, this significant contribution to the toilet was invented in the early 1800s (and patented in 1819) by the little known Albert Giblin.

Crapper took this design more than half a century later and popularised it, succeeding in taking the credit for its invention too. His royally warranted sanitary equipment company was the largest in the UK, and the first to utilise a showroom for mass-produced toiletry wares in 1870, further popularising in-house sanitation and toilet installation.

Crapper did invent several toilet add-ons, most notably adapting Cummings’ ‘S-pipe’ into the modern day ‘U-bend’. He held 9 patents, including the revolutionary ballcock and the unsuccessful ‘self-rising seat’.

His connection with the phrase ‘crapper’ was coincidental, as ‘crap’ had been used in relation to waste long before his lifetime. However, it is likely that the connection to toilets and excrement was strengthened and popularised with the size and success of his company, and ‘crapper’ branding emblazoned across all his products.

Toilets have even been adapted to work in under the low gravity conditions found when orbiting planet Earth. This space toilet design was used onboard Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

Astronaut Clayton C. Anderson shared his experience of using this type of toilet onboard a Soyuz spacecraft in 2007. Anderson is one of a small number of astronauts to have used a space toilet onboard four different spacecraft (a Soyuz, the International Space Station and Space Shuttles Atlantis and Discovery).

Like many inventions, the toilet was developed by numerous additions and adjustments over time, with no single ‘inventor’ who could claim the title. It is up for debate which designs were most significant and influential.

There are many historic innovations we’ve not included here, as well as endless modern innovations such as Japan’s hi-tech loos (some which even play music!) and waterless toilets (which you can see on display in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries).

Sadly flushing toilets continue to be a luxury in many parts of the world. Around 2 billion people worldwide are still without access to basic sanitation such as a toilet. There is much more to be done to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of providing adequate and equitable sanitation for all.

To see some of the key innovations in the history of toilets (and find out what happens when you flush), visit The Secret Life of the Home Gallery at the Science Museum.

The Science Museum will be closed from Thursday 5 November until Thursday 3 December. Booking is now open for admission from 3 – 16 December 2020. Head to our website to read the latest information and to pre-book your free tickets.