In early September 1766, John Dalton was born. He was fascinated by colour blindness, the weather and had one of the most important ideas in the history of science.

Dalton was born in a remote village called Eaglesfield in Cumbria, northwest England, on or around 6 September 1766. His parents were Quakers and Dalton had a modest upbringing.

From childhood, Dalton showed himself to be both clever and inquisitive. He attended the local village school, where he took on a teaching position from the age of 12.

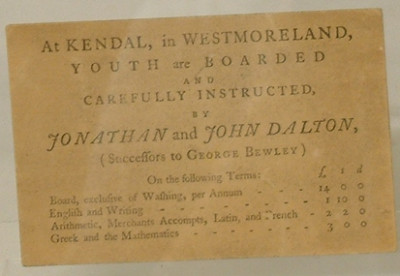

By 15 he was helping his brother, Jonathan, run a Quaker boarding school in Kendal, where they taught subjects ranging from ancient Greek to hydraulics.

Whilst at Kendal, Dalton made the acquaintance of John Gough, a blind scholar and keen amateur meteorologist who helped stimulate Dalton’s lifelong love of science.

Gough encouraged Dalton to start a daily weather diary, which he kept for 57 years. Dalton made over 200,000 observations – often with the help of home-built instruments – and completed his last entry just hours before he died.

Dalton’s weather data provided the material for his first book – Meteorological Observations and Essays – published in 1793.

That year Dalton left Kendal to take up a teaching position at a Presbyterian college in Manchester.

Resigning from the post six years later, he turned to private tutoring to earn a living. Among his pupils was James Prescott Joule, the scientist who gave his name to the standard unit of energy – the joule.

Once resident in Manchester, Dalton became a member of the Literary and Philosophical Society – a discussion group set up to share scientific ideas at a time when science had yet to become a profession. Here he was given access to a well-equipped research laboratory and his scientific output flourished.

Though criticised for the quality of his experiments, Dalton was an enthusiastic investigator who worked late most evenings. In later years he wore a thinking cap, which is now on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

In total, Dalton presented over 100 papers to the society, becoming its president in 1816. One of the earliest papers Dalton presented was on colour blindness – from which both he and his brother suffered.

Colour blindness, he concluded, was caused by a discolouration of the gel-like substance that fills the middle of the eye, known as the vitreous humour.

To test his theory Dalton donated his eyes for examination after death. Autopsy proved his theory to be incorrect. His eyes were retained and DNA analysis in 1995 (150 years after his death) revealed that Dalton suffered from red-green colour blindness – a condition still referred to as daltonism.

In 1808 Dalton placed the idea of the atom on a solid scientific footing with the publication of his book A New System of Chemical Philosophy.

Chemical elements, he declared, are made of atoms of different weights that combine to form new substances – or compounds. During chemical reactions atoms are never created, destroyed or transformed – simply rearranged.

Dalton imagined atoms as solid, hard spheres. In 1810 he asked an engineering friend, Peter Ewart, to make a set of wooden ball-and-stick models to use as teaching aids.

They remain the first known models of atoms and are currently on display in our Dalton anniversary showcase.

Although Dalton’s atomic theory took a long time to be accepted – and not everything he came up with was true – his ideas still form the cornerstone of chemistry today.

In keeping with his Quaker upbringing Dalton lived a humble life and steered clear of public acclaim as far as possible.

He was nonetheless widely honoured in his lifetime, receiving honorary degrees from the universities of Oxford and Edinburgh.

Dalton was especially loved by the people of Manchester. The city paid for a life-size statue to be erected during his lifetime and filed past his coffin in their tens of thousands as he lay in state.

Nine years later they paid for a granite monument to be erected alongside his grave in Ardwick cemetery.

The Dalton anniversary display is on the ground floor of the Science Museum until late 2017.