Marie-Anne Paulze was born on 20 January 1758 in Montbrison, a town in France’s Loire region that is well known for its eponymous blue cheese. She lost her mother when she was just three years old. Shortly after, she was sent to a convent for her education.

Paulze’s father, Jacque, worked for a tax collection company for the French monarchy. When his daughter was twelve, he received an unwelcome marriage proposal from the powerful and very elderly Count d’Amerval.

With threats of losing his job, Jacque successfully blocked the proposal by means of arranging another, with a younger, more suitable bachelor – his colleague, Antoine Lavoisier.

Despite the contrived nature of their marriage, Paulze and Lavoisier were well matched. Lavoisier was a chemist, and Paulze immediately took a keen interest in his work, determined to learn more about the field and join her husband in the laboratory.

Paulze received formal training in chemistry from Lavoisier’s colleagues and she also studied drawing under the famed French artist, Jacques Louis David. Later, Paulze commissioned a double portrait of her and Lavoisier, which the above engraving is based on.

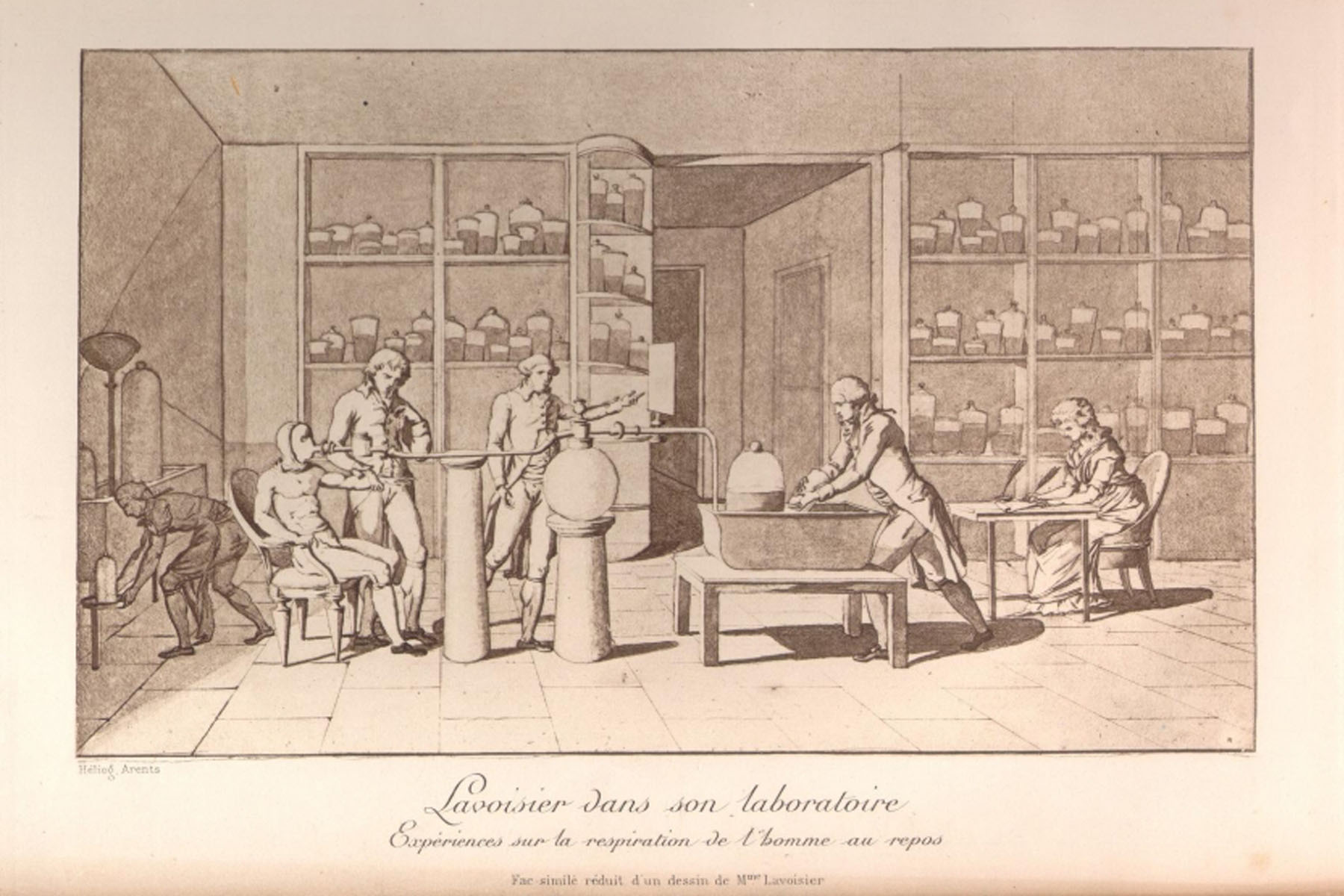

Such was her talent for drawing, that she produced the thirteen copperplate illustrations for Lavoisier’s seminar work, Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (1789), which laid the foundations of modern chemistry and the chemical elements as we know them now. (The Science Museum holds a first edition.)

As well as illustrating, Paulze collaborated with her husband, observing experiments and recording laboratory notes – a part of the scientific process that was depicted in her illustrations.

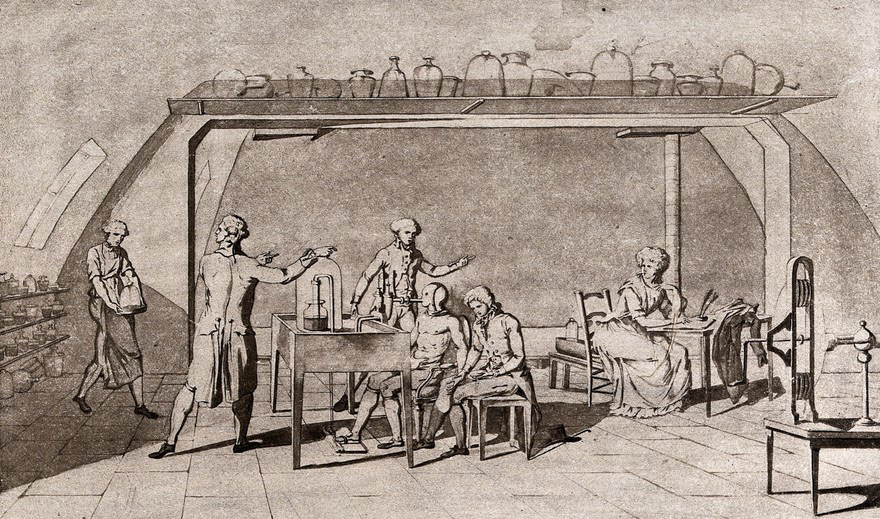

The Science Museum has in its collection a diorama based on this illustration, made by the Wellcome Institute, sometime between 1945 and 1965, when such museum display techniques were in vogue.

The illustration (and diorama) depicts one of a series of experiments on the chemistry and physiology of respiration carried out by the Lavoisiers and their collaborators.

This scene features Antoine Lavoisier, in wig and tailcoat, stood at the table. A physician (possibly Scotsman Hugh Gillan) is taking the pulse of a topless man (chemist Armand Séguin), who is wearing a copper face mask attached to a circulatory breathing apparatus while operating a pedal. Paulze can be seen note-taking.

The scientific interpretation of this experiment and the apparatus, which you can see varies slightly from the original illustration, has confounded historians.

But the general project of this series of experiments was to measure and understand the roles of oxygen and carbon dioxide – gases that had been recently discovered – in respiration.

These respiration experiments were carried out at the Lavoisiers’ home laboratory at the Paris Arsenal. The Lavoisiers worked under a strict regime: 6.00 – 9.00 and 19.00 – 21.00 weekdays; and morning and lunch in the laboratory Saturdays, with theoretical discussions in the afternoon.

Paulze played a vital role in the promotion of their work to the international scientific community, editing publications and keeping her husband Lavoisier abreast of the latest developments.

Unlike Lavoisier, she mastered languages, translating key chemical works, such as those of British chemists Joseph Priestley and Henry Cavendish. Her annotations and comments speak to the depth of her chemical knowledge.

For these reasons, she deserves a place alongside her husband for the successful dissemination of the oxygen theory of combustion (oxidation), which replaced the prevailing phlogiston theory, favoured by the Brits. It would form the basis of the modern classification of the chemical elements.

The Lavoisiers’ marriage did not have a happy ending. Due to his career with the Royal Tax Collectors, Lavoisier was not spared the fate of many of the aristocratic class during the Terrors of the French Revolution. He was guillotined in 1794, at the height of his scientific career.

After her husband’s execution, Paulze organised the publication of his final work, Memoires de Chimie. She authored the preface when his long-time collaborator Séguin (the topless, masked chemist in the diorama) refused to criticise the revolutionaries responsible for Lavoisier’s death.

The affection they shared was evident in the last letter Paulze received from her imprisoned husband on 7 May 1794:

My dearest friend … Be careful not to sacrifice your health, for that would be the greatest misfortune. … I have always enjoyed a happy life. You have made it so …

She did marry again, to another scientific luminary, the physicist Benjamin Thomson, better known as Count Rumford. But it did not last long, the couple divorcing after two months.

Paulze described Rumford as ‘the theoretical liberal’ who in practice was a ‘domestic tyrant’. Rumford’s own assessment was they were both too independent – he was used to getting his way and did not share the same sense of collaboration as Paulze’s first husband.

The pair did once have an amusing public feud. Paulze invited a large number of guests to their Paris home against the wishes of Rumford. Rumford responded by locking the gates and hiding the key. She ended up conversing with them through the gates, and in retaliation pouring boiling water on Rumford’s prized flowers.

Paulze’s later years were occupied by charitable work, but her legacy as a chemist lives on through the work she achieved in her former life together with Lavoisier.