Women have been practicing medicine in Britain for thousands of years. Through the Middle Ages, wise-women or healers treated diseases and other ailments with herbal remedies. They also practiced midwifery – assisting with childbirth – with the word itself coming from the Anglo-Saxon for ‘with women’. Nursing developed as a respected profession for middle-class women during the Crimean War (1853-1856), led by the pioneering work of Florence Nightingale alongside nurses such as Mary Seacole and Betsi Cadwaladr. Barred from British universities, however, women were unable to obtain the qualifications needed to join the Medical Register – a list of licensed doctors established by the Medical Act of 1856. Joseph Lister, the influential ‘father of modern surgery’, argued against the ‘unseemliness and impropriety of having medical topics discussed without restriction in a mixed company of men and women‘. His opinions reflected those of the wider medical establishment, who believed women doctors would disrupt the social order of Victorian Britain.

Yet three pioneering women had the determination and creativity to challenge their exclusion. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), born in Bristol but raised in Ohio in the United States, was inspired by the death of a close friend to pursue medicine. She was accepted to Geneva Medical College in New York after a vote by the male student body, who treated her admission as a practical joke, and she persevered in the face of persistent harassment to become the first women in the United States to receive a medical degree. After visiting Britain to learn more about hospital practice, she was allowed to join the Medical Register under a clause that permitted doctors with foreign degrees obtained before 1858.

Blackwell’s contemporary Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) was rejected from numerous British universities, so became a nurse at Middlesex Hospital in London. Although she wasn’t allowed to enrol in their medical school, she was permitted to attend Latin, Greek and pharmacology classes, and employed her own tutor in anatomy and physiology. After passing the Society of Apothecaries entrance exam with the highest marks on that day, she was admitted in 1862 which gave her a license to practice medicine; the Society immediately changed their rules to prevent other women from doing the same. Both Anderson and Blackwell managed to individually exploit loopholes in the Medical Act, but these loopholes were closed behind them.

Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) sought to change this. Born in Hastings, she attended Queen’s College in London and became passionate about equal rights for women, arguing in an 1869 essay that women could be excellent doctors but needed ‘a fair field’ in medical education. She joined forces with six other women to submit a successful application to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh. However, the Edinburgh Seven – as they became known – faced harassment and abuse, culminating in a riot when they tried to attend their first anatomy exam in 1870, and their places were withdrawn. Undeterred, Jex-Blake became the driving force behind a new medical school that would accept only female students. She gathered a group of medical professionals including Blackwell and Anderson to govern and lecture at the school, secured sympathetic donors, and rented a building in Bloomsbury, London.

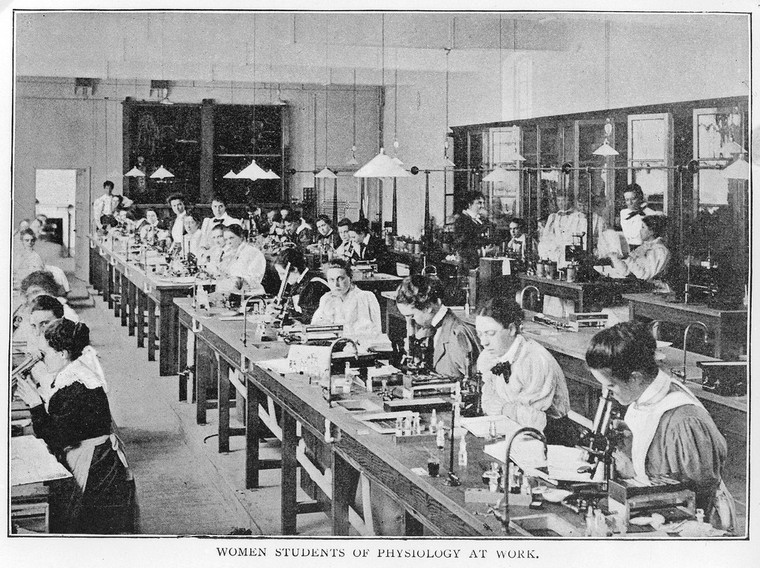

The London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) officially opened with fourteen students on 12 October 1874. The students were given lectures in anatomy, physiology, chemistry, botany, materia medica (medications), mental pathology, surgery, midwifery, and gynaecology. From 1877, a final year of practical training at the Royal Free Hospital was added, meaning graduates could formally register as doctors. In 1881, there were 25 women doctors in Britain; by 1911, there were 495.

Indeed, so many students joined that LSMW moved into a purpose-built building on Handel Street in London, which still stands as an NHS health centre today. Alumni included Louisa Aldrich-Blake (1865-1925), Britain’s first female surgeon who pioneered new treatments for patients with rectal cancer; and Rukhmabai (1864-1955), a social reformer who became one of the first female doctors in colonial India alongside Kadambini Ganguly. Jex-Blake started another medical school for women in Edinburgh where she met Margaret Todd, one of the first students of the school; they developed a relationship that was likely to be romantic, although they were forced to hide this, living together as what Todd called ‘intimate friends’ for the rest of Jex-Blake’s life.

LSMW merged with UCL’s medical school in 1998, ending its 120-year history. The school’s founding principles were defined as ‘educating women in medicine and enabling them to pass such examinations as would place their names on the medical register’. This has certainly been achieved: in 2022, there were approximately 180,000 women registered as medical practitioners in the UK, and more women than men currently attend British medical schools. Although there are still barriers for women and LGBTQ+ people in the sector, we should celebrate the London School of Medicine for Women and the determination of pioneers like Jex-Blake, Anderson, and Blackwell who paved the way for the doctors of today.