Sixty years ago, it seemed inevitable that the USSR would be the first to land a human on the Moon.

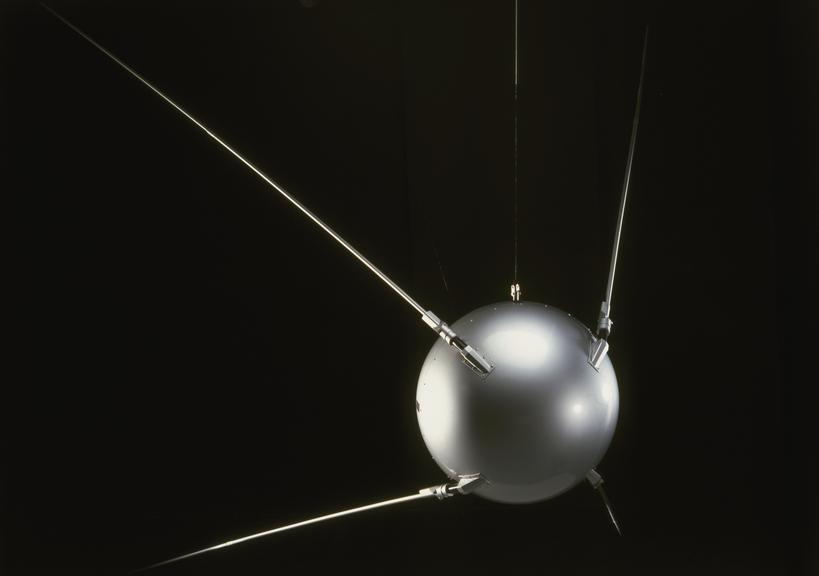

Earlier, on 4 October 1957, the USSR had successfully launched the Sputnik satellite into Earth’s orbit and the “beep beep beep” of Sputnik’s telemetry shook the world.

More firsts quickly followed for the USSR, with Yuri Gagarin becoming the first human in space on 12 April 1961, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in 1963, the Voskhod 1 carried the first multiple-person crew into space in 1964 and the first spacewalk was carried out by Alexei Leonov in 1965.

Because the USSR lunar lander could only be entered by someone who had undertaken a spacewalk, Leonov became an ideal candidate for this mission. At this time, the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo 11 touched down in July 1969, had even been selected as a potential USSR landing site.

Despite the USSR’s isolation from the West, Leonov was well aware of President John F Kennedy’s 1961 speech which launched America’s Apollo Moon programme.

Russian fascination with space long predates that of America. In the later years of the 19th century, cosmism, emerged in Russia led by Nikolai Fedorov (1829-1903), blending ideas from Western and Eastern philosophy along with those of the Russian Orthodox church to ponder the origin, evolution, and future of the cosmos.

While newborn NASA first pondered a lunar programme in November 1959, the year before Sergei Korolev (1907-1966, the master architect of the USSR’s space successes), had already outlined a Moon mission and colony in his ‘Most Promising Works on the Development of Outer Space.’

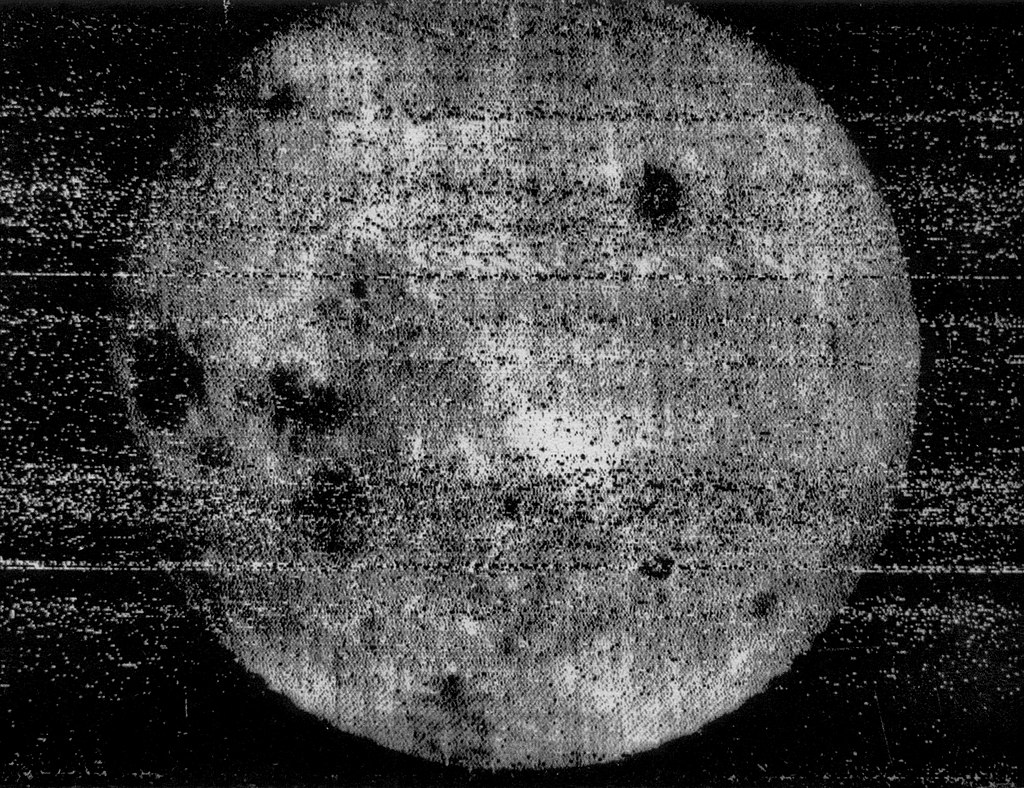

The USSR led the way in lunar exploration with the first probe to impact the Moon (Luna 2, September 1959), the first flyby and image of the far side of the Moon (Luna 3, October 1959) , the first soft landing (Luna 9, February 1966), the first lunar orbiter (Luna 10, March 1966) and the first spacecraft to circle the Moon and return to Earth carrying tortoises, flies, mealworms, plants, seeds and bacteria (Zond 5, September 1968).

It’s important to note that, in 1964, the Soviet government gave the authorisation—undeclared to the world—to proceed with a Moon mission.

Science Museum space curator Doug Millard comments: ‘Kennedy set the US on a course for the Moon in 1961. The Soviet Union waited until 1964 – three years too late?’

Soon after, Leonov began to train for this mission along with Oleg Grigoryevich Makarov (1933-2003).

To prepare for this complex lunar landing, Leonov learned how to cope with high g forces, made regular parachute drops from a helicopter and, since they did not have a Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, would take over the controls of a helicopter during rapid descent from altitudes as little as 100m, or land the helicopter with the engine turned off, when the main rotor turns by autorotation. Despite this, the risks were never far from his mind.

On 27 March 1968, Leonov heard two distant explosions while training a group of cosmonauts in lunar landing techniques. Later that day it emerged that Gagarin had crashed during a training flight in a MiG-15.

The USSR planned for Leonov to land on the Moon in a craft known as the LK (Russian: Лунный корабль, “Lunniy korabl”, meaning “lunar craft”).

An earlier unmanned probe, the Lunokhod rover, would be used to select a landing spot, and then act as a beacon for a backup LK to be sent to the site. The third step would see a manned LK landing with a single cosmonaut. The Lunokhod would also provide the means to reach the backup LK, if needed.

Like America’s Apollo programme, the Soviets wanted to use a giant rocket for Its lunar mission, and their N1 was similar in height to the American Saturn V rocket. But the N1 project was rushed and the engines never fully tested before the first launch attempt in February 1969. All four launch attempts ended in failure – the first N1 rocket lasted a minute, the second collapsed onto the launch pad, the third disintegrated and the fourth exploded.

The next step was, of course, to plant a flag.

On July 21, 1969, the world was glued to its television screens as Neil Armstrong and then Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon in the Apollo 11 mission.

Leonov went to a research center in Moscow to watch his American rivals. The Russian Luna 15 mission, designed to return soil samples from the lunar surface, underwent its mission at the same time as Apollo 11, and the need to coordinate these missions marked a rare example of cooperation between the world’s space superpowers.

Doug Millard, Space Curator, commented that Chris Kraft, Apollo mission planner, was uneasy about the Soviets’ Luna 15 being present during the Apollo 11 landing.

When Neil Armstrong set his left boot on the lunar surface on July 21, 1969, he spoke the now-famous words, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Leonov also thought hard about his own first moments on the Moon’s surface.

Overall, one could sense Leonov’s frustration with the limits of the USSR’s Moon ambitions.

The Zond 5 mission of September 1968, which carried tortoises and other Earthlings, also contained a mannequin cast in the image of Yuri Gagarin, studded with radiation detectors, for the trip around the Moon and back to Earth.

Downcast, Leonov told the audience at a Science Museum IMAX event how the USSR programme could have taken one more step towards the Moon as ‘six spacecraft orbited the Moon without a man on board.’

Roger Highfield interviewed Alexei Leonov when the museum opened its Cosmonauts exhibition in 2015.