[Curator Liz Bruton looks straight to camera]: Now where to begin?

The first thing you need to know is that Enola Holmes, a Netflix film released in September 2020, depicts the social, political and technological developments of Victorian Britain – a world on the brink of change in the mid-1880s. Here, we meet Enola Holmes, the sixteen-year old younger sister of Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes played charmingly by Millie Bobby Brown.

Enola has been brought up a “wild child” (at least according to her brothers) or rather a curious and intelligent young woman, broadly educated by her mother Eudoria in astronomy, beekeeping, reading, scientific experimentation, sports including Ju-jitsu, and mental exercises such as word games and chess – all subjects widely represented within the Science Museum Group collections.

Which leads me onto the second thing you need to know: on the day of her sixteenth birthday, Enola awakes to find her mother Eudoria has left their countryside home and has gone missing. Enola calls in her older brothers, the famous young detective Sherlock Holmes and Mycroft Holmes, to help find her mother but soon realises it is up to her to solve the mystery herself.

This leads (spoilers ahead!) to her ditching her brothers and heading to London to search for her missing mother and becomes involved in the case of the missing Viscount wrapped within the wider political context of feminism, suffragettes, and the Third Reform Act, a law to extend male suffrage or the right to vote.

Alongside the politics of 1880s Britain, Enola Holmes demonstrates various Victorians technologies available – if not always affordable – to the masses, in particular bicycles, steam trains, and cipher wheels. But what are the true stories behind their dramatic version? The game is afoot…

“Bicycles are not my core strength”

Enola Holmes opens dramatically with our central character pedalling furiously on her safety bicycle, noting when she comes a cropper that “bicycles are not my core strength”. Enola speeding along on her bicycle echoes the front cover of The Case of the Missing Marquess, the first novel in the young adult fiction series The Enola Holmes Mysteries by Nancy Springer – Enola Holmes did not appear in the original Sherlock Holmes series by Arthur Conan Doyle.

The modern bicycle has its origins in developments in cycling in the late 1800s, including developments such as pedal drives, tyres, and frame design. In the 1860s, the ‘boneshaker’ bicycle was developed in France and became widely around the world including in Britain.

It was the first bicycle with a pedal drive so the bicycle’s motion was powered by pedal motion rather than feet along the ground. However, ‘boneshaker’ bicycles had two different sized wheels and was an uncomfortable ride.

Another bicycle with uneven wheels was the penny farthing or ‘ordinary’ bicycle, popular from the 1870s onwards. With a large front wheel, these bicycles could go further with each turn of the pedals – but riding so high up was awkward, unstable, and dangerous.

Lastly, the modern bicycle reached fruition with the Rover ‘safety bicycle’ designed by British inventor John Kemp Starley and introduced in 1885. It had all the basic features of standard modern bicycles, including a diamond frame, chain drive to the back wheel, and equal-sized wheels. These features meant the bicycle became an easier and safer ride, leading to cycling becoming enormously popular, among both men and women.

Women became involved in cycling for transport, leisure and racing by the late 1890s and for some it was a form of social mobility and feminism. Enola Holmes’ cycling as an expression of her independence, feminism and rapid transport reflects the wider experiences of women and cycling in the late 1800s although her bicycle in 1884 would have been more likely to have been a ‘boneshaker’ or penny farthing rather than the ‘safety bicycle’, which was only available from 1885 onwards.

“I don’t want to die on a train”

In “phase 2” of her plan to find her missing mother, Enola escapes her brothers and meets Viscount Tewkesbury on a passenger steam train travelling to London. In reality, this is Great Western Railway (GWR) steam locomotive 2857 and vintage carriages belonging to the Severn Valley Railway, a full-size standard-gauge railway line, running regular, mainly steam-hauled, passenger trains between Kidderminster in Worcestershire and Bridgnorth in Shropshire. The steam locomotive GWR 2857 was completed in April 1918 and was designed to haul goods rather than passengers.

Rail travel in Britain has originated with Robert Stephenson’s Rocket and the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (L&MR) railway locomotion trails at Rainhill in October 1829. The outcome of the trails was to determine which design for a self-propelled steam locomotive could be used for the efficient transport of goods and passengers as Britain’s Industrial Revolution thundered ahead. This was a story of innovation, ingenuity and personal rivalry which led to a world-changing transport revolution.

Between 1829 and the early 1900s, Britain pioneered the more revolutionary development of railways, delivering significant economic and social benefits and transforming the transport of goods and passengers. A train used in 1884 would have looked more like NER 0-6-0 ‘1001’ class steam locomotive and tender, No 1275, 1874, in use from 1874 to 1923 and now on display in the Great Hall at the National Railway Museum.

Trains like this would have transported passengers and goods throughout Britain from the mid-1800s onwards. However, corridors connecting compartments and carriages were not introduced until around 1900 which would have made for a much shorter chase scene and so a far less exciting and life-threatening journey as that experienced by Enola Holmes and Viscount Tewkesbury in Enola Holmes!

“Mother can untangle anything I need to make it most devious”

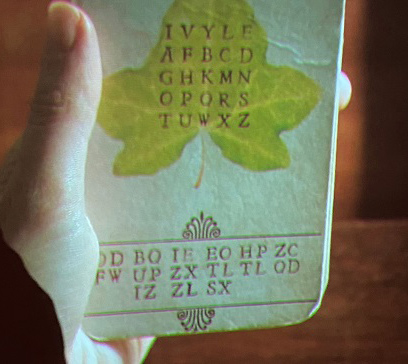

Codes and cipher disks form a central part of the mystery of the disappearance of Enola’s mother Eudoria. After eventually arriving in London, Enola places a series of encrypted messages in different London newspapers in the hope that her mother will read and decipher them and reply in turn. We learn that word play was a favourite hobby of Eudoria’s and that she had taught Enola how to use codes and ciphers to send and receive secret messages.

Enola eventually receives a reply, allegedly from her mother, and uses the cipher disk or cipher wheel left behind by her mother to decipher the message to reveal the original message of the newspaper advertisement. This is true to Victorian newspaper advertisements which did sometimes feature secret messages left in the personal or advertisement columns of newspapers.

Cipher wheels were developed from the mid-1800s to automate encryption. They took each letter of a message and moved it down the alphabet a fixed number of places to produce the encrypted message. Telegraph pioneer Charles Wheatstone developed the Cryptograph cipher wheel around 1870. It could encrypt telegraph messages quickly and easily but was also insecure as the cipher could be easily broken.

Conclusion

Enola Holmes depicts a world on the brink of political, social and technological change – from bicycles bringing independent transport and mobility to the masses, including women, through to trains transporting goods and people at speed across the land and increasing the urbanisation of Britain. These technologies created new networks of communications and transport and with increased communication came the need to send secure messages, enabled by cipher wheels and other means of encryption.

Although this Netflix film depicts specific examples of bicycles and trains not yet available in the time setting of 1884, more broadly the film has much to teach us about the late Victorian technologies of trains, bicycles and cipher wheels transforming people’s lives – especially women’s lives – and the world in the 1880s.

Sources and further reading

Enola Holmes (2020): https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7846844/ and https://www.netflix.com/watch/81277950

Science Museum blog: PERILOUS PENNY-FARTHINGS: https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/perilous-penny-farthings/

National Railway Museum’s object and stories: STEPHENSON’S ROCKET, RAINHILL AND THE RISE OF THE LOCOMOTIVE: https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/stephensons-rocket-rainhill-and-rise-locomotive

The cryptograms appearing in the movie “Enola Holmes”: https://www.wissenschaft.de/scienceblogs/the-cryptograms-appearing-in-the-movie-enola-holmes-klausis-krypto-kolumne/

Severn Valley Railway: https://www.svr.co.uk

One comment on “The true stories behind the tech in Enola Holmes”

Comments are closed.

You missed out the motor car and Bertha Benz!