Tim Harford, Undercover Economist at the Financial Times explores the objects in the Science Museum that have shaped our economy.

The world economy can be bewildering. All too often it’s a system that we discuss using abstract terms such as “fiscal” or “gross domestic product”. But of course this apparently-abstract thing we call “the economy” has profound consequences for the way we live. With seven billion people making countless choices every day, buying and selling around ten billion distinct types of product or service, the economy defies our understanding. Ripples in the system can make fortunes, cause environmental devastation, lift people out of grinding poverty, or throw them into joblessness.

One of the joys of writing the book and BBC radio series Fifty Things That Made the Modern Economy has been getting specific – picking an idea or an everyday object and telling the story of how it shaped our economy. Did you know that the first writing was developed by accountants? Or that the Romans were big fans of concrete? Or that the Houses of Parliament burned to the ground when some hapless civil servants decided to dispose of obsolete financial records by setting fire to them?

But a visit to the Science Museum takes the story still further, because some of the leading actors in this story are on display. Here are five of my favourites.

Google search: There’s a server – a computer that responds to online requests – from the early days of Google. It’s amazing that this company, barely two decades old, has become a gatekeeper to vast swathes of the online economy. Many businesses succeed or fail based on whether the Google search algorithm thinks they’re the best answer to a question typed into the search bar.

iPhone: Staying with the world of computing, you can admire an iPhone– assuming you don’t already have one in your pocket – and compare it to other phones and computers. The history of the iPhone is a fascinating one: it’s a triumph for the entrepreneur Steve Jobs at Apple. But it’s also a wonderful advertisement for the power of government research, since many of the key features of the phone – from web access to a touch-screen to the location-detecting GPS system – were originally developed by governments, often the US military.

The Pill: There’s more to technology than computing, of course. Wander over to the Who Am I? Gallery and look at the contraceptive pill; the pill is often identified as a socially revolutionary invention, but economists believed it unleashed an economic revolution, too. By giving women more reliable and discrete control over their fertility, the pill encouraged young women in the 1970s to postpone marriage and children, and move into long professional training courses, becoming doctors, dentists, and lawyers.

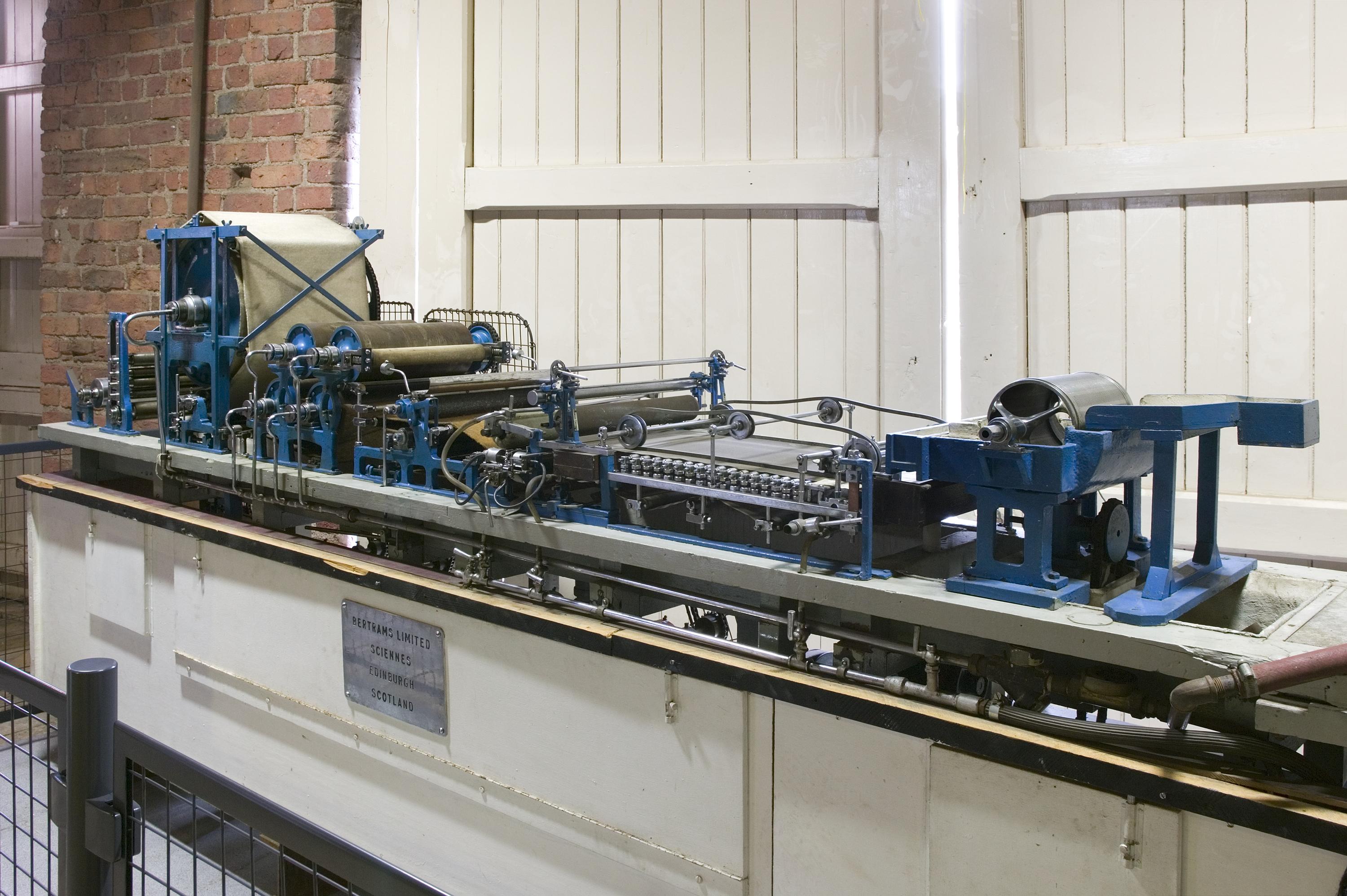

Paper: I have a soft spot for the under- rated inventions. Everybody likes to talk about the significance of the Gutenberg printing press – but the printing press would have been pointless without a cheap writing material. That material was paper. When Europe belatedly embraced paper – long after China and the Arab world – it became arguably the continent’s first heavy industry, in the 13th century. Only then did the printing press make sense. And our hunger for paper continued, with the Fourdrinier Machine of the late 19th century a major step forward in paper production.

Robots: Finally, the technology everyone is talking about at the moment: robots. Will they take all our jobs? Perhaps: but the employment rate in the UK has never been higher than it is today, in mid – 2017. There are 100 robots to admire in the museum’s special robot exhibition: go and meet them, and see if you can make sense of the mystery of a robot economy in which so many humans are still working so hard.