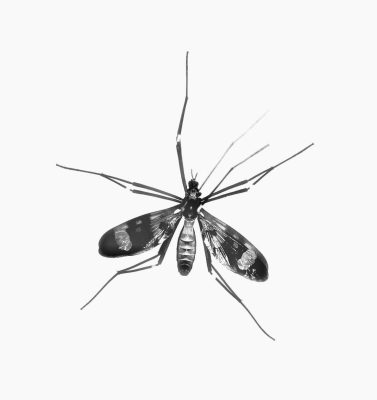

I had read Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ so I knew what was happening: I was turning into a mosquito. She bit me at a writers festival. I’d just started working on a novel about interspecies communication and this mosquito shared a disease with me called chikungunya – meaning, in Kimakonde, ‘that which bends up’, for the pained and twisted state of its victims. Australian friends, unable to pronounce the word, would call it ‘chicken dinner’. Either way, my skin peeled off, translucent as wings. The fever sent me delirious – I saw the world insect. My body stayed arthritic and twisted, not quite human, for two years. I had been abducted, altered, and returned quite changed.

Years later, when I won the 2021 Arthur C Clarke Award – given to the best science fiction novel published in the UK each year – director Tom Hunter described The Animals in That Country as a ‘first contact novel’ and I heard the buzzing. I thought again about that mosquito – how that moment of bitten exchange is to enter another world, and how power can shift and metamorphose in that space. I was aware that I had written a speculative fiction novel, but wasn’t quite sure how science fiction readers would take it. Was it science enough? Had I followed, broken or tropified the rules? To be welcomed into The Clarke Award family was to be drawn into another sort of universe (much more lovely than chikungunya) – a judging panel made up of the British Science Fiction Association, the Science Fiction Foundation, and the Sci-Fi-London film festival and a shortlist with such writers as Patience Agbabi, Simon Jimenez, Hao Jingfang, R.B. Kelly and Valerie Valdes! To say I was over the moon was an understatement.

Entering this space also confirmed a few things I’d been puzzling over for the seven years I’d worked on the novel: that a moment of encounter with another animal – with a wild animal on a walk, or one who might otherwise be named food or vermin, or a companion pet – is to have a more-than-human experience akin to first contact with life forms on other planets. Could a moment between a woman and a dog be as thrilling as stories that reach as far as the stars or into the depth of disease? Here we are sharing a planet with creatures with such extraordinary abilities – sonar, flight and deep blue sentience; creatures whose presence among us remains undiscovered and incomprehensible; those who we rely on heavily for companionship, symbolism, food and materials. How would a life form from another planet perceive this complex, violent and entwinned relationship?

There’s a scene in Douglas Adams’ The Restaurant at the End of the Universe where a cow character approaches a table of human diners and announces, ‘“I am the main Dish of the Day. May I interest you in parts of my body?”’ The humans are, by and large, horrified, exclaiming, ‘“I just don’t want to eat an animal that’s standing there inviting me to [–] it’s heartless.”’ In Douglas’ imagination, we travel to the far reaches of the universe to have this conversation. One of the many wonderful aspects of a ‘voyage to the edge of the imagination’ – The Science Museum’s fantastic exhibition theme – is that this discovery starts right here. The next time we see an ant bearing incredible weight, or a bird dipping through the sky in the majesty of flight, a cow in a field using complex social structures to communicate, or the neighbour’s old dog with his extraordinary sense of smell, we have the chance to step outside our human world, and into another.

Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of Imagination at the Science Museum until 20 August 2023. Book your tickets now