Bessie Coleman was the first African American woman to receive a pilot’s licence. A skilled pilot and ‘daredevil aviatrix’, she championed opportunities for women and Black people in aviation.

Born in Texas on 26 January 1892, Coleman was one of thirteen children. From a young age, she helped her sharecropper mother pick cotton to pay their rent after her father left the family. Yet she showed an aptitude for academia, regularly visiting the local library and becoming the family bookkeeper at eight years old. Studious Coleman completed every grade at her one-room segregated school, achieved a scholarship to a Baptist school, and saved up to train as a teacher at university. There, she read about famous aviators and, although she couldn’t afford to return for a second term, developed an interest in flying.

Coleman initially dismissed a career in aviation, however, because women were not allowed to fly in the US. In 1915, at the age of 23, she travelled to Chicago to live with her brothers and attended beauty school to become a manicurist. Her brother John had served during the First World War in France where women could become pilots. One day, he exclaimed “Black women ain’t never goin’ to fly, not like women in France.” Smiling, Coleman replied, “That’s it! You just called it for me.” She became determined to prove him wrong.

Coleman applied to several flying schools across the US. Though none would take her, she persevered, saying ‘Every no takes me closer to a yes’. She sought the advice of Robert Abbott, the publisher of the Chicago Defender newspaper and an advocate for Black people, whom she met upon winning a manicurist competition held by the paper. Abbott encouraged her to go to France. Inspired, Coleman began French lessons, took up a second, higher-paying job and approached benefactors. Finally, she was accepted into the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy in the north of France

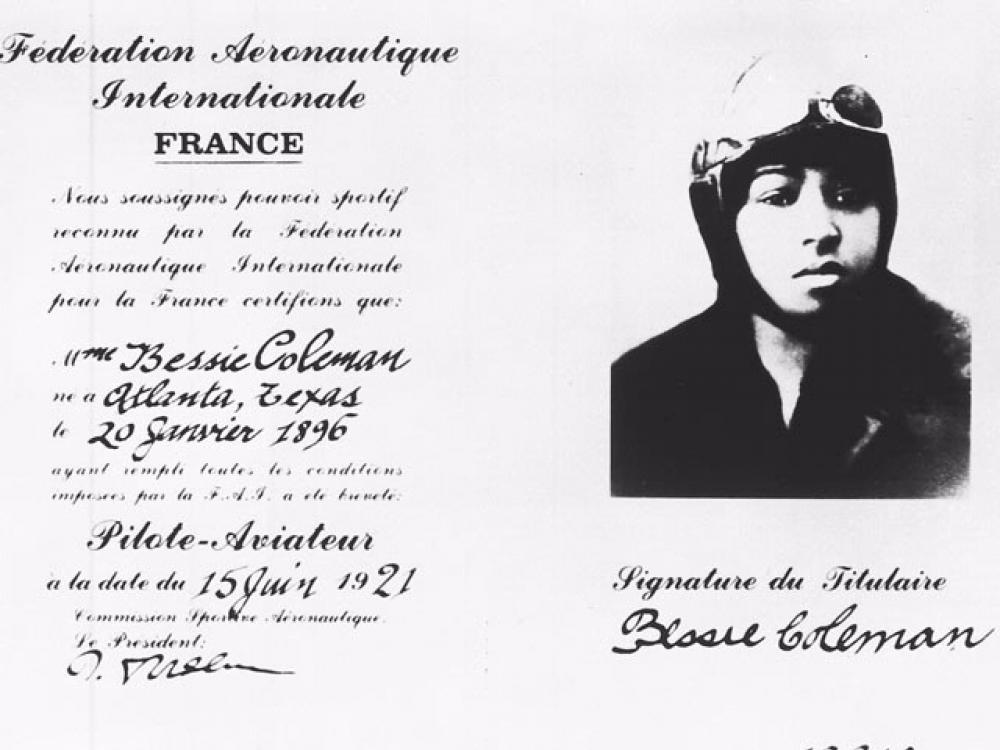

The aeroplane in which Coleman learned to fly was a Nieuport 82 dual-controlled trainer biplane. It was difficult to control, with a rudder for steering and a stick dragged along the ground to break upon landing. She remained determined despite witnessing a fatal accident, saying it was a “terrible shock to my nerves, but I never lost them.” On 15 June 1921, she became the first African American woman to receive an international pilot’s licence.

Coleman completed additional training in ‘barnstorming’, the style of flying that would make her famous. Derived from flying through the open doors of a barn, barnstorming involved daredevil stunts like loop-the-loops, walking on the wings, and parachuting out of an aeroplane. Having mastered this, Coleman returned to the US in 1922 and performed the first public flight by an African American woman. She attracted interest amongst the international Black press, fashioned herself into a barnstorming celebrity with a glamorous military-style costume, and earned the nicknames ‘Queen Bess’ and ‘Brave Bessie’.

Coleman used her fame to fight for opportunities for Black people. Her ultimate dream was to open a flying school for Black people in the US. She toured the country teaching African Americans and women to fly and refused to perform anywhere that discriminated against them. Coleman even turned down a leading role in a film based on her life when she realized it began with her dressed in rags, despite longing to support its African American cast and crew.

By 1926, Coleman almost had enough money from her beauty business to open a flying school. On 30April, she took her new aeroplane for a test flight the day before its first airshow with co-pilot William Willis. Sitting in the passenger seat, Coleman unbuckled her seatbelt and peered over the side for a parachute jump location. At that moment, a wrench became stuck in the engine and Willis lost control. The aeroplane suddenly accelerated, nose-dived, and flipped. Coleman was thrown out at 2,000 feet, while Willis crashed nearby. Neither of them survived.

The mainstream press barely noted Coleman’s death, focusing instead on Wills who was white. Yet African Americans celebrated Coleman’s life. Her body lay in state, activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett delivered the eulogy at one of her three funerals, and around 10,000 people attended her memorial service. For years, aeroplanes flew annually over her grave.

In 1929, Coleman’s dreams were fulfilled when the Bessie Coleman Aero Club was established by Black aviator Lt. William J. Powell. Aircraft clubs, manufacturers, and scholarships took her name, coins and stamps bore her image, and in 2000 she was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. Coleman paved the way for female African American aviators like Willa Brown and Janet Bragg, and when Mae Jemison became the first African American woman in space in 1992, she carried a picture of her heroine, Bessie Coleman.