Nicknamed “Maggie the Indestructible”, Margaret Bourke-White was the world’s first female war correspondent. Born on 14 June 1904 in the Bronx, New York, Margaret would go on to travel the world and capture some of the most important moments of the 20th century.

In the course of her career, she gained intimate access to famous subjects including Joseph Stalin, Haile Selassie, Winston Churchill, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and Mohandas Gandhi just hours before his assassination. But more than anything else, Margaret documented the lives of ordinary people through industrialisation, war, shifting borders and state violence.

Her tenacity and boldness allowed her to break into and photograph male-only spaces from industrial steel mills to war zones. In her incredible memoir, Portrait of Myself, she explains her unique perspective in the male-dominated field of photography:

‘Usually I was the only woman photographer, and the technique I followed was to literally crawl between the legs of my competitors and pop my head and camera up for part of a second before the competition slapped me down again. At least, the point of view was different from that of the others whose pictures were, perforce, almost identical, and, anyway, I’ve always liked “the caterpillar view.”’

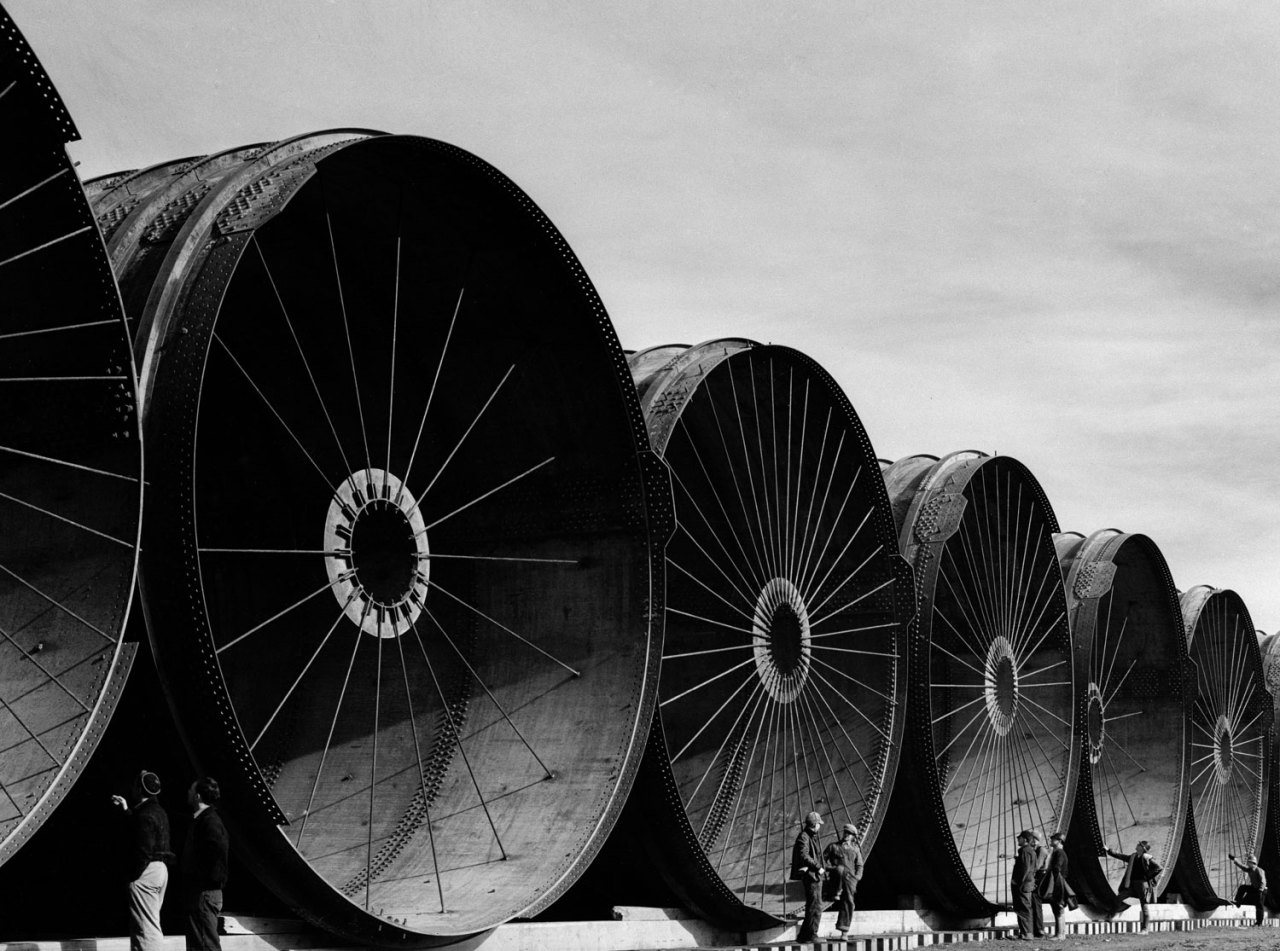

Margaret was inspired to learn photography at a young age from her father, who was an amateur photographer and brought Margaret along when he made pictures. Margaret followed, pretending to take photographs of her own with an empty cigar box. Her memoir reminisces about a time he took her on a business trip to a steel foundry. At that moment, she felt that “a foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty…[it] was so vivid and alive that it shaped the whole course of my career.” At university, Margaret studied herpetology (a branch of zoology focused on amphibians and reptiles) while taking photography classes with fine arts photographer, Clarence White. After the death of her father in her first year, she switched her academic focus to photography. As soon as she graduated, Margaret moved to Cleveland, Ohio and opened a studio that focused on architectural and industrial photography. Throughout her career, her work reflected this first love of structural forms and the aesthetic intensity of scale and harsh lines.

In 1928, Margaret was hired by the Otis Steel Company to photograph their industrial mills. When her camera had trouble adapting to the red and orange lights of hot steel in the mills, she brought in a magnesium flare. The bright white illumination helped light the scenes and resulted in a formidable set of high contrast photographs that brought to life the heat of the American steel industry.

This set of photographs caught the eye of Fortune magazine founder Henry Luce, who brought Margaret’s photography to a mass public audience. Her projects for Fortune gave her the opportunity to travel and photograph a range of industries. In 1930, she travelled to the Soviet Union: the first Western photographer allowed to enter the region. During her stay, she documented the first Five-Year Plan as well as capturing portraits of Joseph Stalin, his mother, and his great aunt.

In 1936, Luce bought the magazine Life. While keeping its original title, he dramatically changed the publication to become the first all-photographic American news magazine. He hired Life’s first female photojournalist, Margaret. Her image of the Fort Peck Dam graced the magazine’s first front cover following the relaunch. The magazine went on to dominate the market for decades.

During the Second World War, Margaret was the only foreign correspondent allowed into the Soviet Union, where she captured the German invasion of Moscow. She was America’s first uniformed female war correspondent. She travelled with the US army to multiple fronts, including at the liberation of Buchenwald concentration camp, where she captured her well-known, haunting image of the camp survivors. She then travelled to South Asia, where she documented the violence and displacement of the partition of India and Pakistan following the region’s independence from Britain.

Margaret Bourke-White provided social and political commentary through her photographs. Over the course of four decades, she travelled the world, throwing herself into war zones and crises to help raise awareness and advocate for human rights. Ultimately her portfolio included the documentation of the Great Depression and segregation in America, the Korean War, and Apartheid in South Africa, among many more historical moments.

After a life of smashing glass ceilings, Margaret died at the age of 67 in 1971 from Parkinson’s disease. Her legacy as one of the most influential photojournalists of the 20th century lives on. Happy 119th birthday, Margaret Bourke-White!