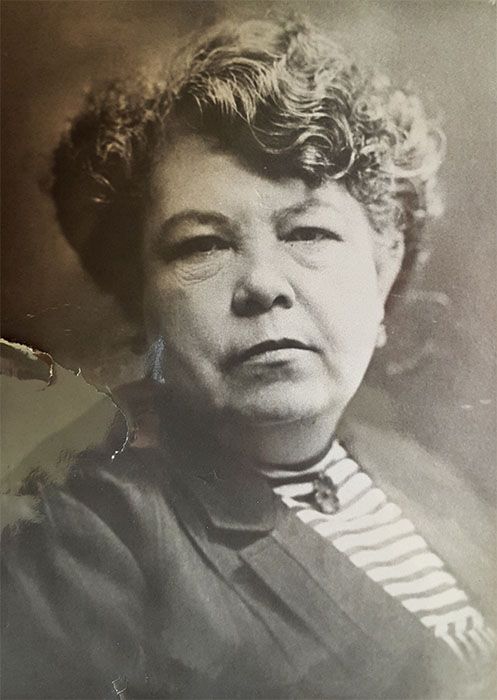

Born on 14 March 1859 in Mexico City, Mexico, Matilde Petra Montoya Lafragua was brought up as though an only child, following the death of her sister.

Montoya always showed an interest in studying, having learnt how to read and write when she was just four years old. She was strongly encouraged by her mother, Soledad Lafragua, to pursue the educational opportunities that she had herself lacked. With her mother’s consistent support, Montoya completed her primary education at 12 years old. As she was too young for secondary school, she was denied entry and her mother continued her education privately.

Eager to pursue a medical career, Montoya enrolled as a trainee midwife in Mexico’s School of Obstetrics and Midwifery, affiliated with the National School of Medicine, at only 13 years of age. She practised in a hospital in the Southern Mexican city of San Andres Cholula, but was temporarily forced to abandon this path due to the money troubles faced by her family following the death of her father.

Montoya ultimately obtained her midwifery qualification at the age of 16 by completing her training at a maternity home in the state of Puebla that cared for unmarried mothers. She began working as a surgeon’s assistant and took private classes in anatomy to complete her midwifery studies, which had only focused on the female reproductive system.

Despite her success as a midwife, and being popular with her patients, Montoya received abuse from some male doctors who thought it ‘unnatural’ for a woman to work in medicine. At the time, it was not possible for women to train as doctors in Mexico, which was a right that women were laboriously starting to win across the world: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had just become Britain’s first female doctor ten years before 1865. Montoya’s critics orchestrated a campaign against her in local newspapers with reports describing her as ‘an indecent and dangerous woman who pretends to become a doctor’.

Undeterred, Montoya applied to the National School of Medicine in Mexico City. Although her first application was rejected, she was finally accepted at 24 years old by the institution’s principal, Francisco Ortega. Her acceptance was met with hostility from the university, with some surgeons and students attempting to make her leave on the grounds that the school referred to ‘alumnos’ (male students), and not ‘alumnas’ (female students). These objections led to her removal from the school, and she was forbidden from continuing her studies.

Montoya took matters into her own hands and wrote a letter to the President of Mexico, Porfirio Díaz, requesting that she be reinstated at the school. Diaz, an advocate for middle- and upper-class women’s rights to education, instructed authorities at the university to allow her to continue her studies.

By persisting – and resisting the constraints put on her as a woman – Montoya graduated from medical school in 1887 and became the first female doctor in Mexico. Recognition for her achievements finally came with this event. Díaz and his wife, for example, attended her graduation ceremony to congratulate Montoya and the press acknowledged her as the first ‘medica’ (the word for a female doctor in Spanish) in Mexico.

Montoya practiced medicine until the end of her life, specialising in gynaecology and paediatrics. She operated two private surgeries in Mexico City, charging patients only what they could afford. She provided services to pregnant women and treated what she called ‘diseases of the waist’ (what we would call gynaecological surgical cases).

Montoya continued advocating for equal access to education for women. While she was shunned by medical associations and academics, which only accepted men, she represented Mexico at the Second Pan American Conference of Women in 1923 in Mexico City and in 1925 she co-founded the Mexican Association of Female Doctors with Dr Aurora Uribe, a young Mexican doctor.

Montoya died in Mexico City in 1939 at the age of 79. She never married but did adopt four children. She paved the way for Mexican women to access professional higher education and pursue a career in medicine. Her legacy lies in the further 83 women that had graduated from Mexico’s principal medical school at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City by 1937 and that in 2018, over 68% of students in the faculty of medicine were women. Today, women represent over 40% of the Mexican medical workforce, and 80% of nurses.

Today, Montoya is commemorated by a bust in the courtyard of the Ministry of Health. The citation reads “Matilde P Montoya, example of tenacity in the pursuit of what for some was a ridiculous dream… she opened the way to science for Mexican women at the end of the last century”.