Looking beyond the one-to-one or person-to-person model of telephones we know and understand today, Bell and others suggested that the telephone could be used for one-to-many communication. Across the Western world, from Budapest to Dallas, engineers set to work creating ‘circular telephones’ – telephones that would be used to live-stream entertainment into the home. In France, Clement Ader had great success placing microphones along the footlights of theatrical performances and running telephone cables through the Parisian sewer network. The Théâtrophone was created in 1881, and shortly after a company in England bought the British patent for this technology. The Electrophone arrived in England, and the London Electrophone Company started trading in 1895.

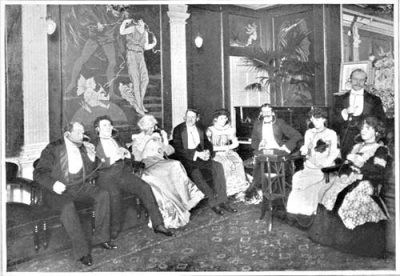

The Electrophone was a sort-of upside-down pair of headphones that fine Victorian ladies and gentlemen would hold under their chins. The headset was connected, through telephone lines, to music halls, churches, and theatres, generally in the London area. Users would call the Electrophone Exchange, based in London’s Gerrard Street, either through their main telephone or a special Electrophone receiver if they paid a particularly high subscription fee. They could then ask to be connected to a range of venues, including the Covent Garden Opera (today known as the Royal Opera House). For as long as they fancied, they would listen in from the footlights of a theatre or a secret microphone hidden within a fake Bible in Church. During this period, their telephone would be disconnected so no one else could make a call – rather like the early dial-up internet experience over telephone lines which some blog readers may remember.

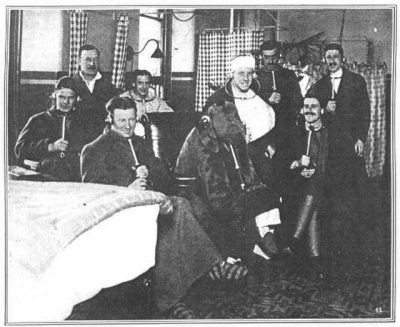

In 2018, an Electrophone table was acquired by the Science Museum. The Electrophone table, which had enough hooks for six headsets to be hung upside down from the top of the table, was only provided to subscribers that paid the higher fee (at least £10 a year to rent four headsets), although given the Electrophone Company’s penchant for freebies it’s possible it could also have acquired one by being a good friend of the company. After the First World War, the Electrophone Company managing director H.S.J. Booth had a row with the General Post Office (who managed and essentially managed telecommunications in the UK at this time) because he refused to stop providing free Electrophone services to soldiers injured in battle.

The Science Museum Electrophone table was owned by H.J. Round, a senior electronic and radio engineer and inventor employed by the Marconi Company for most of his career, the same company responsible for the advent of radio broadcasting. Round personally assisted Marconi on a number of experiments and was the first to discover that electricity passing through a solid-state diode could cause the diode to light up, which would later lead to the discovery of LEDs.

Before the First World War, Round was a significant figure in the development of radio valves, which meant voices could be broadcast using wireless waves and this would lead to broadcast radio similar to how we know it today. After the First World War, Round worked on radio transmitters with Marconi, becoming Chief Engineer of the company in 1921. By the time Round was invited to work on sonar during the Second World War he ran his own consulting business.

Round died in Bognor Regis, Dorset, so there are a number of ways he might have got his hands on an Electrophone table. Bournemouth, Dorset, had the longest running Electrophone service in the UK, with the business only closing down in 1938 when they realised there were just two subscribers left. Round could have been one of these Dorset-based Electrophone lovers, or maybe it was something to do with his work in radio. The Electrophone served a slightly different purpose to early radio, as it was so focused on live events happening in London, and it’s possible Round saw value in the novel medium as well as his own wireless set.

Similar to most Electrophone tables remaining, Round’s kit does not have a set of headphones with it, nor the special Electrophone receiver you’d expect to find in the homes of wealthier subscribers. There are very few of these around today, and the majority of headsets you see are ones made by fellow Electrophone enthusiasts keen to see for themselves how the technology worked. People have been doing this as long as the Electrophone has existed, with the Model Engineer publishing an article in 1910 about how to make your own headset.

The Electrophone fell out of use a few times over its existence, with dwindling subscription numbers firstly in the 1910s and again towards the end of the business, when the Electrophone Company ceased operating in 1925. The General Post Office (GPO), who assumed responsibility for managing Britain’s telephone lines after the National Telephone Company closed in 1912 in addition to their previous and general responsibilities for licensing telecommunications in the UK, noted that the Electrophone Company often failed to keep its subscribers for very long. The object was seen as a novel item you might rent from time to time, rather than a serious bit of technology required for everyday life.

Despite co-existing with early broadcast radio in the 1920s, today the Electrophone is nowhere near as remembered or discussed as the wireless. This is understandable, given radio is still seen in our everyday lives while the Electrophone is not.

Another challenge facing the Electrophones living memory is the relative lack of surviving Electrophones available in the UK. In 1925, when the Electrophone Company closed due to dwindling profits and pressure from the GPO, the Postmaster General issued an order for all equipment to be collected and destroyed. Some of the devices were probably not all thrown away, but instead recycled and used in other equipment of the time.

However, alongside the Electrophone table and a primary switch for Electrophone stage transmitters in Science Museum Group collections, there are rare surviving examples in Amberley Museum, the Museum of London, the National Museums of Scotland, Milton Keynes Museum, and some in private collections.

These surviving objects, especially those in museum collections, are one way to keep the memory of the Electrophone system alive and give more people opportunity to learn the story of the Electrophone.

FURTHER READING

https://www.britishtelephones.com/Electrophone.htm

Electrophone: the Victorian-era gadget that was a precursor to live-streaming by Natasha Kitcher: https://theconversation.com/Electrophone-the-victorian-era-gadget-that-was-a-precursor-to-live-streaming-148944

https://earlyradiohistory.us/1903lond.htm

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/connecting-britain/electrophone-invention/