Researchers have discovered a little RNA molecule – small enough to potentially form spontaneously, yet sophisticated enough to begin to copy itself – that could explain how life on Earth bootstrapped itself into existence from lifeless chemistry more than four billion years ago.

For decades, biologists have struggled with a chicken or egg problem: did molecules such as DNA and RNA, which store instructions (like a recipe book) come first, or proteins which, like a chef following a recipe, do all the work in the body?

Ever since scientists found that one kind of RNA molecule, called a ribozyme (RNA enzyme) can do the job of both storing information and act like proteins, carrying out chemical reactions such as copying other RNA molecules, there has been huge interest in whether life’s origins lay with RNA.

But there was a catch: after three decades of studies focused mostly on one RNA lineage, scientists could not make these ribozymes copy themselves, probably because they were too long (more than 150 chemical ‘letters’).

Today, in the journal Science Philipp Holliger’s team working on the first floor of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge (LMB) has unveiled a much smaller RNA molecule, named QT45 (where 45 refers to the number of chemical units it contains), that can copy itself.

Moreover, compared with earlier and longer RNAs, QT45 should be much easier to form spontaneously, complementing research by another LMB researcher, John Sutherland, who showed the building blocks of RNA can be produced under conditions plausible in early Earth, along with efforts to study chemicals that were present in the early solar system, revealed in samples collected by Japan’s Hayabusa probe from an asteroid, for example.

Lead author of the Science paper, Edoardo Gianni, said: ‘This research offers a glimpse into what the earliest steps of life might have looked like. By identifying a small RNA with this activity, it makes the whole idea that self-replicating RNA emerged spontaneously much more likely, and thanks to its size, it managed to copy all of itself.’

The discovery dates back six years, to when he decided to ‘take a bit of a gamble’ as he finished his PhD, looking for a distraction while writing up his thesis. Rather than tinkering with existing ribozymes, he generated small, random RNA sequences, creating a vast library of a trillion (a million million) different kinds.

He subjected them to round after round of selection, keeping only those sequences that showed any ability to copy RNA, no matter how feeble. With each cycle, the best was mutated and tested again.

After three months of fruitless experiments, he was greeted by the sudden appearance of a band on a gel, a telltale sign of RNA replication. He had found QT45. ‘I remember walking back with the gel and another PhD student in my year seeing my smile and asking if I got a result.’

Since then, the MRC team has confirmed the ability of QT45 to copy various RNA sequences and ultimately to synthesise itself (though they have yet to demonstrate QT45, or its descendants, can take part in a self-propagating cycle of replication). It can also be stripped back to 35 letters, and still work, albeit with even lower efficiency.

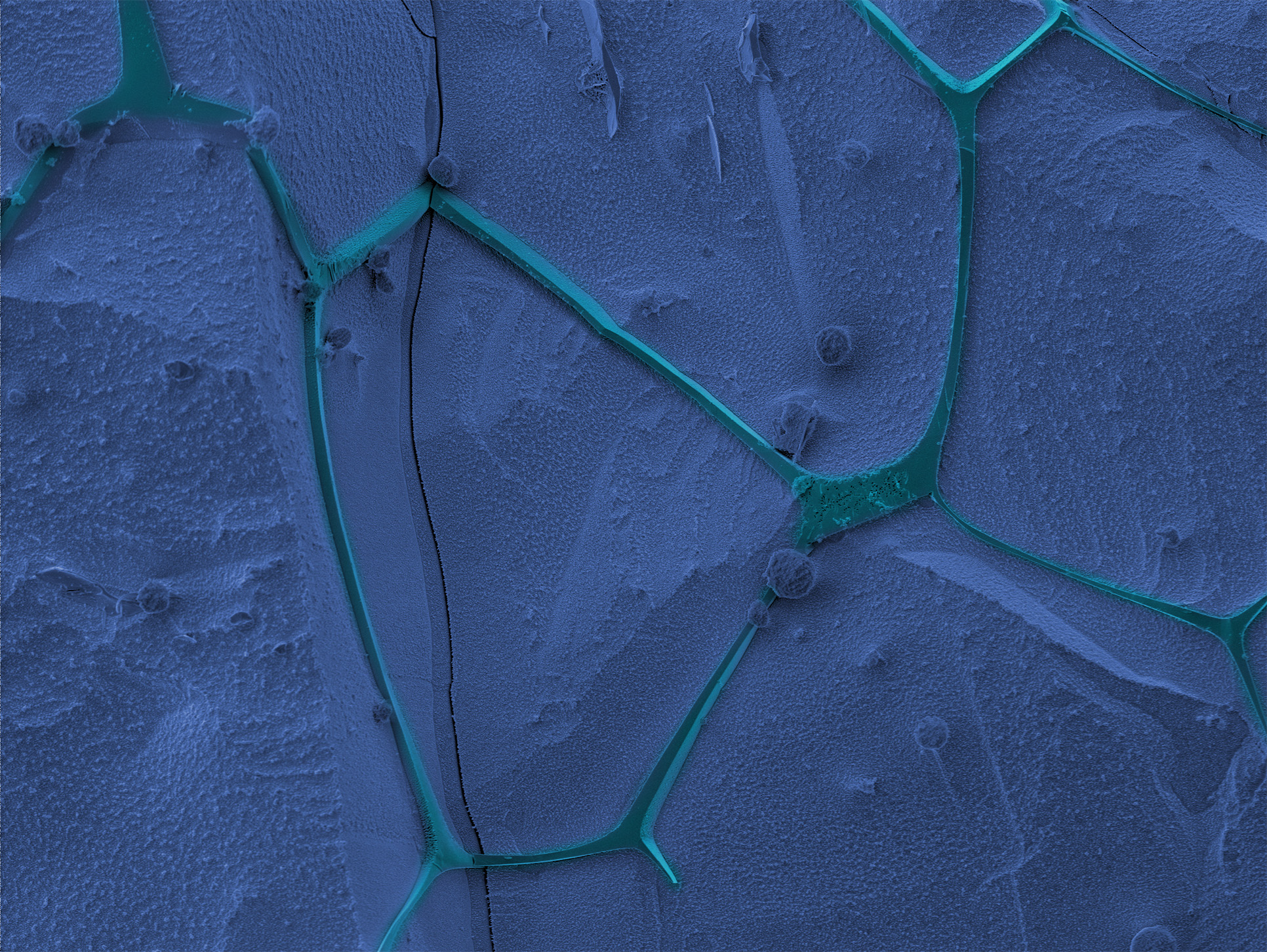

And the team found that QT45 replicates in mildly alkaline, icy conditions of the kind that might have existed on early Earth.

This is significant because, when water freezes, it forms ice crystals and pushes dissolved chemicals into liquid pockets, boosting concentrations and promoting some chemical reactions, albeit ones that are much slower than at room temperature. Moreover, the frozen conditions help stabilize RNA, which tends to fall apart at higher temperatures.

That, he says, may suggest life didn’t begin in Darwin’s ‘warm little pond’ but somewhere stranger: perhaps close to the poles in a ‘hydrothermal pond’, where volcanic heat meets freezing water, environments like those found in Iceland today. ‘You get freezing, thawing, high temperatures, and variations in pH,’ he said. ‘That provides more options for interesting chemistry to happen.’

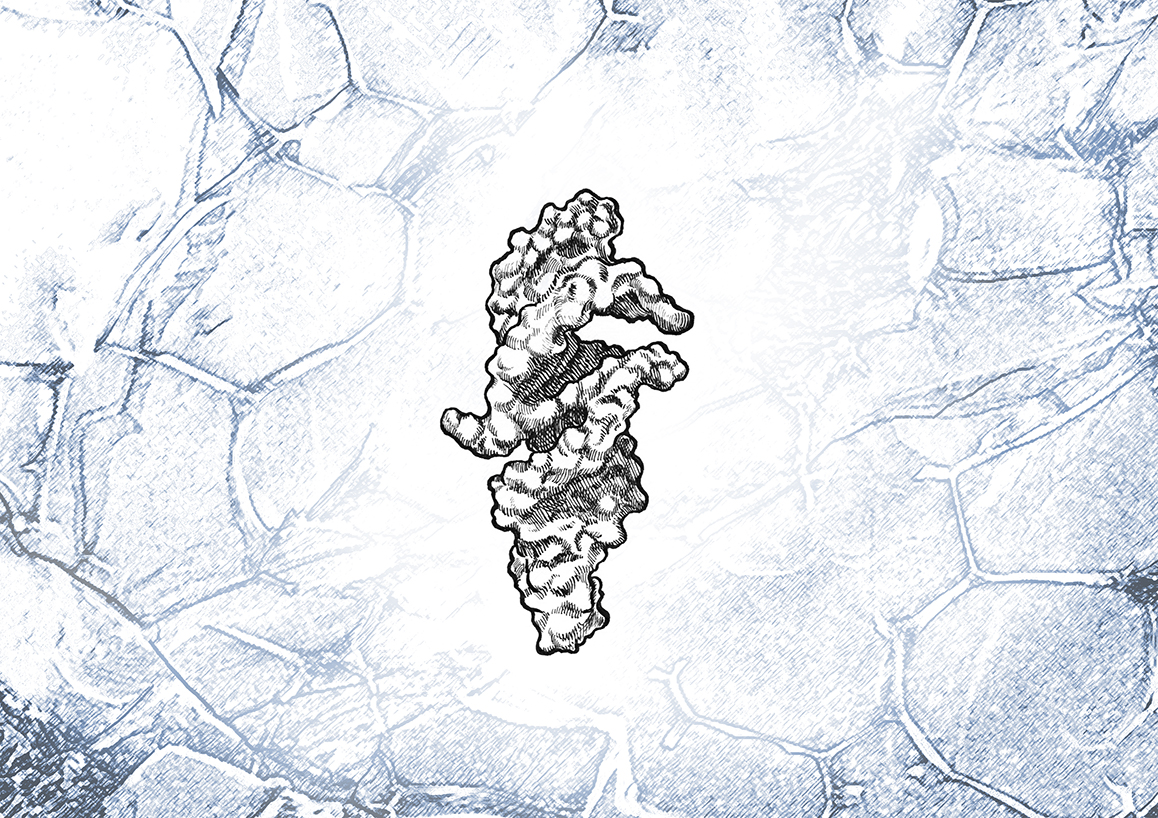

The team has tried using AI – in the form of AlphaFold – to predict QT45’s three-dimensional structure, which might reveal how it works and whether similar ribozymes lurk in modern cells.

The implication of their work also extends beyond Earth, said Edoardo Gianni. If RNA-based self-replication can emerge from relatively simple chemistry, as QT45 suggests, then the threshold for life may be lower than previously thought and life could be more ubiquitous.

The Holliger team at LMB is now attempting to create a self-sustaining cycle, recreating in a Cambridge lab what may have taken place in primordial icy regions four billion years ago: the moment lifeless chemistry became biology, setting in motion a chemical chain reaction that would eventually produce Shakespeare, space telescopes and scientists clever enough to reconstruct their own origins.