What’s the connection between the Great British Bake Off and nineteenth-century chef Alexis Soyer? Well, I guess the blog title gives it away: food consumed – not literally – but as public spectacle.

Outside of the more intimate settings of our home kitchens, the return of Bake Off to our TV screens shows that there is a real appetite for what is frankly (light entertainment) food porn watched by millions. In Bake Off a series of amateur bakers are challenged by celebrity chefs and comedians to produce a series of baked goods armed with a range of modern kitchen equipment and techniques – the winner sometimes becoming a celebrity in their own right.

In the 1950s, the infamous Kruschev-Nixon kitchen debate at the American National Exhibition of American goods in Moscow was seen to epitomise the heady face-off between Soviet communism and American consumerism. Kitchen kit even became a hot 2015 election topic in Britain as the media dissected the meaning behind the gadgets, condiments and kitchen appliances of David and Samatha Cameron’s kitchen.

But cooking as spectacle and celebrity chefdom are not a new phenomenon.

Chef Alexis Benoît Soyer, a name unfamiliar to most today, was one of the most well known figures of mid 19th century Britain. A tall charismatic Frenchman with a distinctive jauntily-angled hat, he became first chef at the London Reform Club where he cooked between 1837 and 1850. He was also one of the first celebrity chefs.

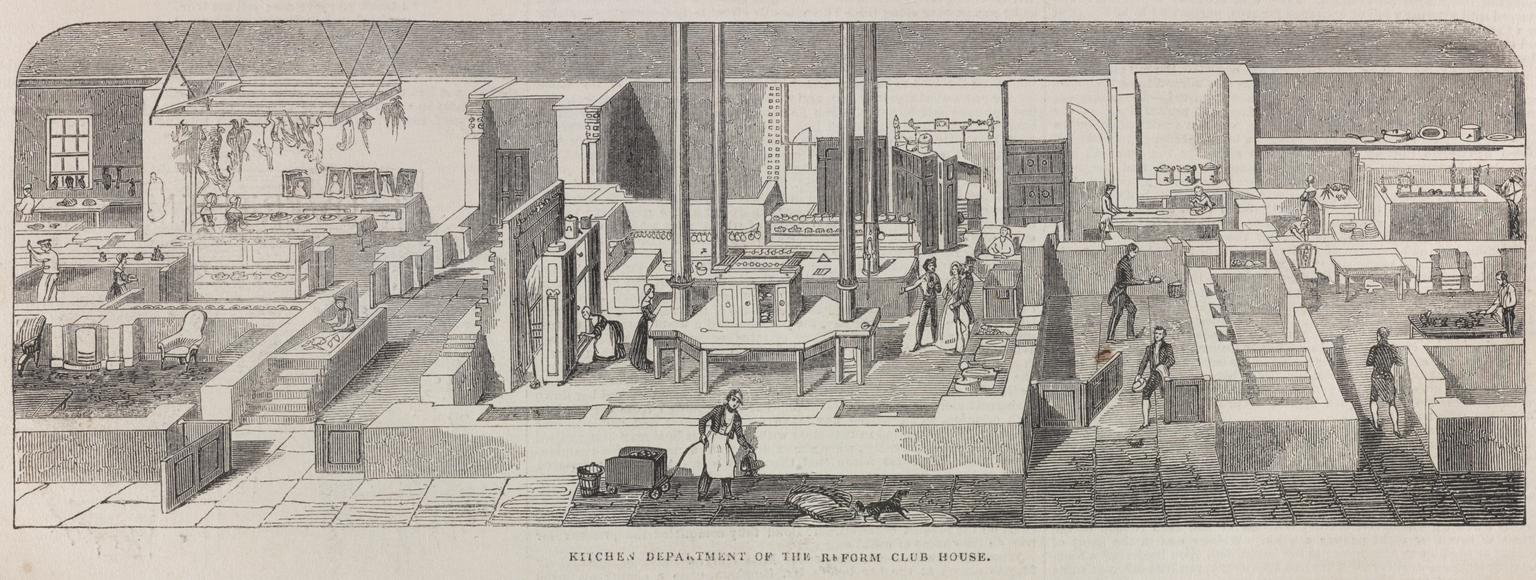

The rich and famous flocked to see his Reform Club kitchen in the mid-nineteenth century. His initiatives to feed the impoverished London Huguenot silk weavers, the Irish Famine poor (whom he stepped up to cook for in their thousands in 1847 at the height of the famine), his cooking for Crimean soldiers and a string of kitchen gadget inventions and cookbooks ensured that his was a household name among contemporaries. Crosse and Blackwell even sold a range of food with Soyer’s name and picture on the bottles.

Soyer planned and oversaw the introduction of what was arguably the world’s most technologically-advanced kitchen at the Reform Club in 1842. The kitchen area was huge and certainly more dazzlingly cutting edge than the Bake Off kitchen.

It used gas-powered cooking which was in its infancy at most at the time and also had temperature controlled ovens, alongside a suite of ice-chilled drawer, slabs and cabinets and multiple kitchen prep and storage areas. Soyer even opened a restaurant up the road from the Science Museum in 1851 on the site of the present Royal Albert Hall, selling flamboyant dishes based on the contemporaneous 1851 Great Exhibition’s main exhibition themes.

Whilst the poorest homes sometimes had no kitchen at all, for wealthier Victorians the kitchen certainly wasn’t the place of public spectacle and chef-worship it sometimes seems to be today.

Most kitchens were hidden away at the back of the house, keeping cooking smells, hustle and bustle and kitchen staff away from the rest of the household. Victorian kitchens did however contain a variety of kitchen gadgets to rival any a 21st century show (or Bake Off) kitchen.

Victorian kitchen cupboards were crammed full of contemporary gadgets – bean slicers, canning equipment, whisks, dangerous looking mixers, a range of jelly moulds, cast iron cookware, spoons and ladles, sitting alongside ice-cream makers, cauldrons and kettles. Fast forward 100 years, and 1950s kitchen demonstrators used a mixture of brand new appliances (cookers and refrigerators) and sales charisma and to create fabulous dishes and sell appliances to an eager audience of mid 20th-century housewives (and it was mainly housewives).

From pop-up toasters to horse-drawn vacuum cleaners, take a closer look at the development of household appliances in our Secret Life of the Home gallery.

One comment on “Kitchen Spectacular”

Comments are closed.

We had Fanny Farmer and Julia Child. CHILD’S kitchen is now in the SmithsonIan and is striking for how humble it is. There is a great show once on public broadcastingrecreating “Fanny Last Meal.” What an operation. THEY made their own gelatin