Earlier this month I watched 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time. I’m glad, for it meant I could experience it properly for the first time on the Science Museum’s 60-foot IMAX screen.

I am not usually especially interested in a film’s special effects, but throughout watching 2001 I couldn’t help wondering , ‘how did they do that?’

One of the most visually impressive scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece is the famous ‘Stargate Sequence’. This comes at the climax of the film (don’t worry, no spoilers). It is a visually stunning, psychedelic feast of colours. It feels as if you were experiencing a supernova through the hallucinating vision of an LSD-fuelled Tim Leary disciple.

Stanley Kubrick on the set of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’. Credit: Warner Brothers

It came as a (welcome) surprise to discover Kubrick had turned to chemistry to create the ‘star gate’ effects.

As Michael Benson has revealed in a recent book on the making of the film, Kubrick began experimenting on what would become this scene in the unlikely setting of an abandoned brasserie factory in New York.

In the factory he and his team set up a series of square water tanks containing a mixture of black ink and a toxic WW2-era paint thinner called banana oil – isoamyl acetate, to chemists. Under incredibly-bright lights and cameras, Kubrick captured the dramatic reactions and colour changes produced when adding paints and various other chemicals to the tanks.

Christiane Kubrick, wife and collaborator of Stanley, recalls the factory experiments were ‘unspeakably disgusting’, as bacteria grew on the materials, causing a stench. Her husband would return home in the early hours, eyes red and swollen from the chemical fumes, to painstakingly record each chemical combination and the effect so it could be replicated.

Chemists also make use of a technique that involves water tanks and colours, known as thin-layer chromatography. Their purpose is to separate chemicals, rather than create cinematographic artistry. We have one of these tanks in our collection.

Kubrick had a background in photography, which had a profound influence on his meticulous filmmaking practice. As a student, he experimented with photochemical processes in a dark room – possibly formative experiences for the water tank techniques he deployed in 2001, in collaboration with the special-effects guru Douglas Trumbull.

Chemistry is not a theme that crops up much in Kubrick films. But there is a notable example in probably my favourite, the wickedly-satirical Cold War comedy Dr. Strangelove (1964).

Without giving too much away, the psychotically-paranoid General Jack D. Ripper responsible for sparking the nuclear crisis of the film is driven by a belief that America is being poisoned by communists.

The method of poison? Fluoride in the water. Chewing on a cigar, Ripper exclaims ‘fluoridation is the most monstrously conceived and dangerous communist plot we have ever had to face’.

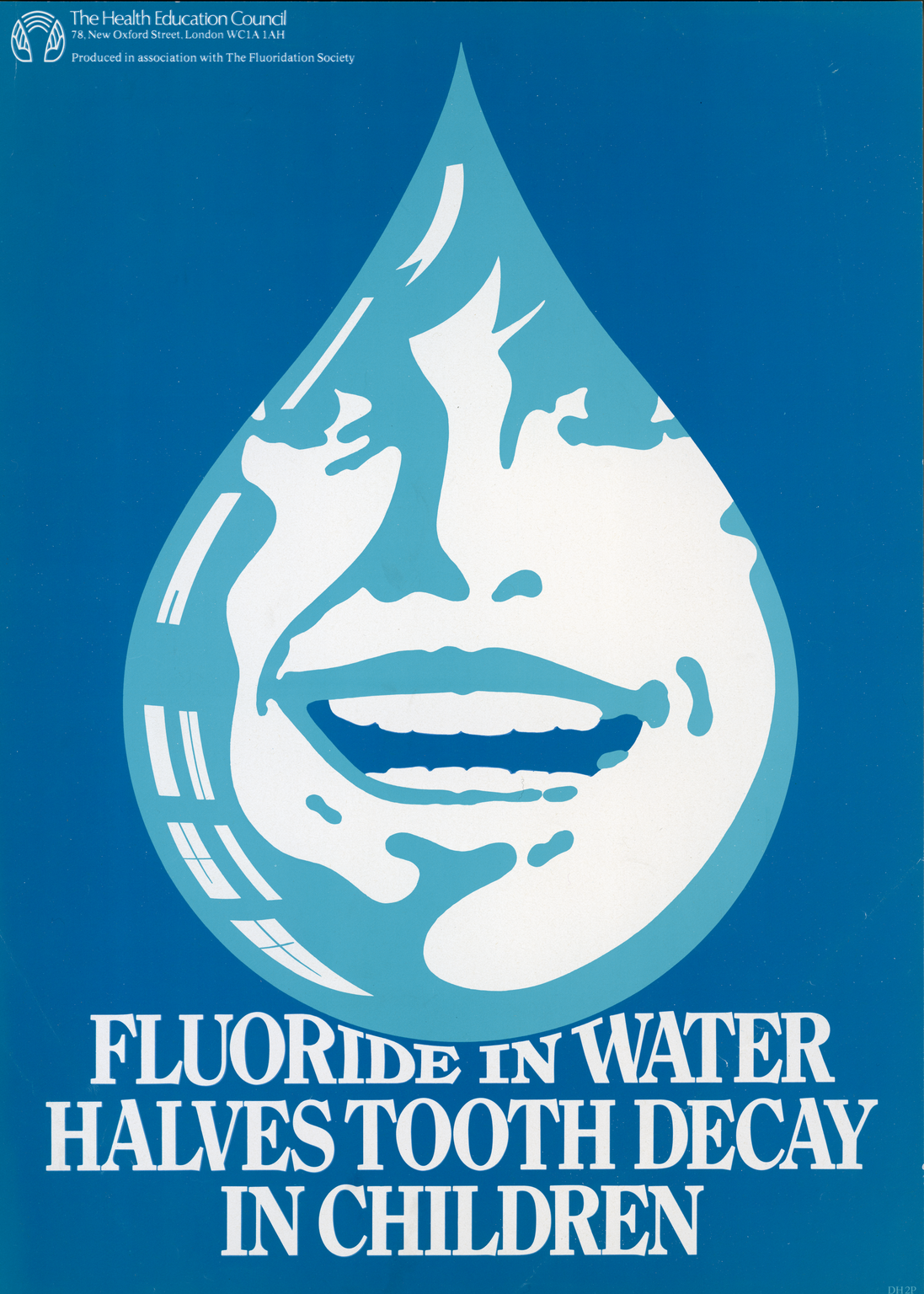

Fluoride, a staple of toothpastes, had been introduced to US water supplies just after the Second World War (and some UK water from 1964) to combat tooth decay. However, it was largely left-wing liberals, rather than communist-fearing military generals, who opposed its introduction.

Over half of America drinks fluoridated water today. The public debate about its consequences for health remains, though convincing evidence supporting its risks has yet to surface.

For now, if you’re heading to the IMAX Theatre to catch the film, fortify your gnashers with some popcorn while you enjoy the chemical mastery of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey on the big screen.