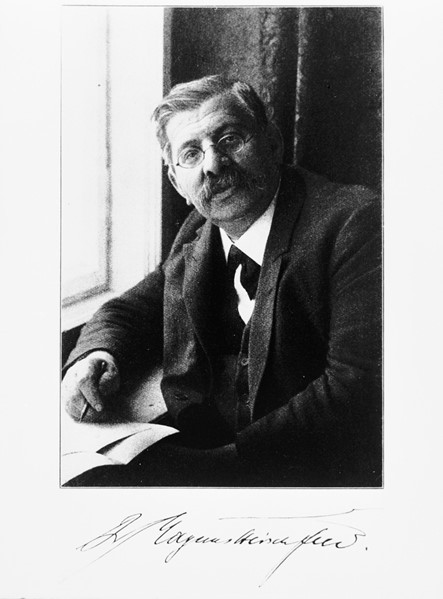

Magnus Hirschfeld (1868 – 1935) was a German Jewish doctor, sexologist and activist who founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (hereafter translated to the Institute for Sexual Science). Hirschfeld was one of the foremost researchers in sexuality and gender in the early twentieth century.

Hirschfeld was gay but never publicly came out and did not mention his own orientation in his scientific publications on sexuality. It was, after all, still illegal to be homosexual in Germany during his lifetime.

Nevertheless, he was invested in using science to improve the lives of those in what people now refer to as the LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer +) community. He operated under the ethos ‘through science to justice.’ His public professional image was that of a scholar and doctor who argued against homophobia and other forms of prejudice from a place of scientific principle.

Hirschfeld’s romantic relationships with men were a secret to all but those in Berlin’s queer community. He was in a long-term relationship with the archivist Karle Giese. Later in his life, he was in a relationship with his protegee Li Shiu Tong. Both were named in Hirschfeld’s will.

Theories on sexuality

From the end of the nineteenth century, the study of human sexuality had begun to be approached as a scientific enterprise. Like many of his middle-class contemporaries, Hirschfeld believed that science was the best lens through which to seek to understand gender and sexuality.

During the tolerant years of the Weimar Republic, Germany (and Berlin in particular) had a reputation of being socially progressive. Many of Hirschfeld’s theories were developed before this period when the country was more conservative. His theories were considered extremely liberal by his contemporaries.

He went against the traditional idea that same-sex attraction was a moral deficiency or a perversion of “natural” sexuality. Many doctors believed that same-sex attraction should be treated like an illness. Hirschfeld, however, argued that all sexual orientations are natural because sexuality is an inborn biological characteristic that one is born with. He stated there was no connection between someone’s sexual orientation and their character.

Theories on gender

Hirschfeld was one of the first theorists to believe that there are gender identities that lie outside of the male-female binary. He observed that some individuals’ sense of gender is contrary to the sex assigned at birth. We now refer to these people as being ‘transgender’ or ‘trans’.

Significantly, Hirschfeld believed that trans people were acting in accordance with their true nature, not against it. He believed that they should be able to present themselves in a way that affirmed their gender identity. He thought that science should provide a means for trans people to medically transition (if this is what they wished to do).

Over 100 years later, Magnus Hirschfield’s thoughts on gender are relevant to discussions among modern scientists about the distinction between biological sex and gender identity. Gender refers to behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man or non-binary that are socially constructed. This means understanding of gender can vary from society to society and can change over time.

Activism

Hirschfeld engaged in many forms of activism and awareness-raising activities to further the rights of LGBTQ+ communities. He published books, journal articles and pamphlets to share his research on gender and sexuality with the public.

In 1897, he founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. As the first ever LGBTQ+ advocacy group, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee campaigned to overturn Paragraph 175 of the German penal code (the section that criminalised same-sex relations between men).

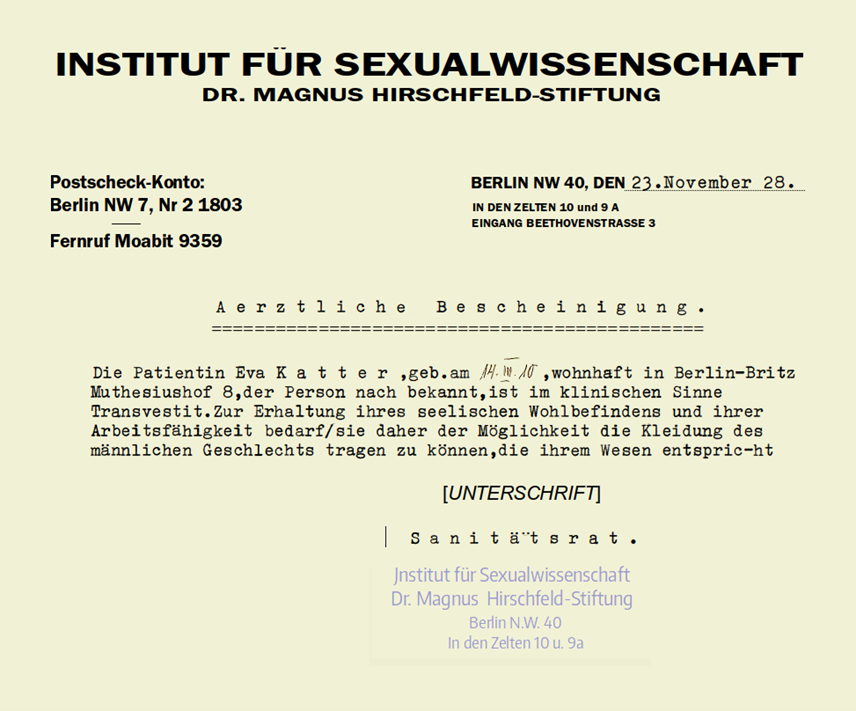

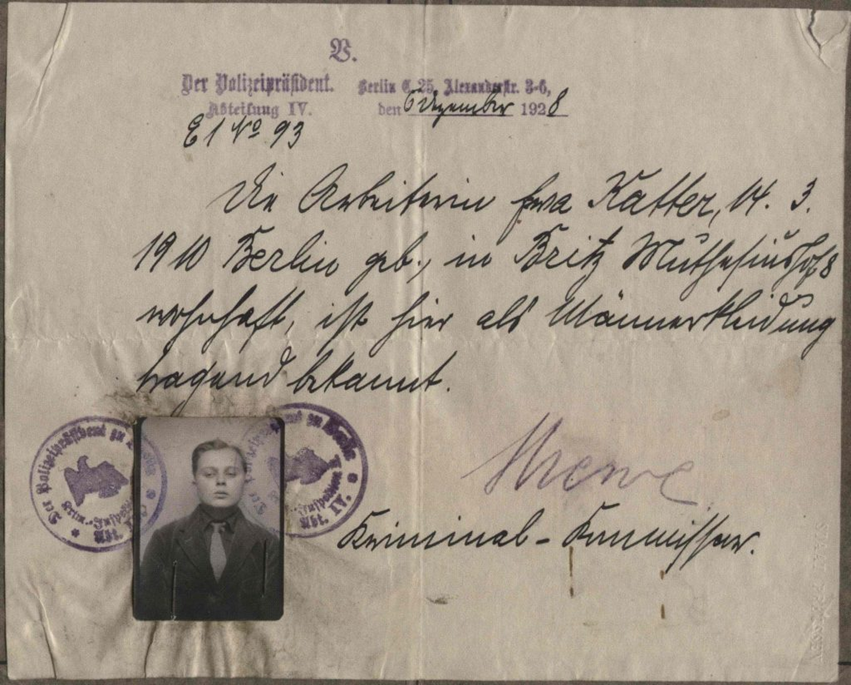

Hirschfeld fostered good personal relationships with law enforcement and instilled in them progressive attitudes. He worked with the Berlin Police Department to educate officers on gender non-conformity and the needs of trans people. To protect his transgender patients from harassment Hirschfeld presented them with a medical certificate. This explained that their gender expression was aligned with their true nature.

The Berlin Chief of Police subsequently issued permits for transgender people that gave them express permission to dress in a way that affirmed their gender identity and protected them from being arrested or charged with the criminal offence of exhibitionism. This helped many transgender people in Berlin, including 19-year-old Gerda von Zobeltitz in 1912, and 18-year-old Gerd Katter in 1928.

The Institute for Sexual Science

Many of Hirschfeld’s queer patients faced discrimination and struggled with self-acceptance, and tragically many would die by suicide due to this. Following their deaths, Hirschfeld decided to leave his practice to create a dedicated facility to treat and advocate for gender and sexual minorities.

The Institute for Sexual Science was opened in 1919. The institution offered medical services, counselling, and sex education to the queer community. Here, Hirschfield continued to undertake research. He collected an immense library and archive containing thousands of scientific books, journals, medical diagrams, and examples of erotica. The Institute soon became a community hub for queer people in Berlin.

Gender-affirming healthcare

While most of Hirschfield’s contemporaries sought to “cure” transgender patients of their alleged mental illness, Hirschfield supported his transgender patients as he believed they should be allowed to embrace their true nature.

The Institute for Sexual Science performed some of the very first male-to-female gender affirming surgeries on trans women experiencing gender dysphoria. Conducted by gynaecologist Ludwig Levy-Lens and surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt, the treatment occurred in a series of stages: castration, penectomy, and vaginoplasty.

In 1922, Dora Richter, an employee at the Institute, began her medical transition. She underwent a series of surgeries, completing her transition in 1931.

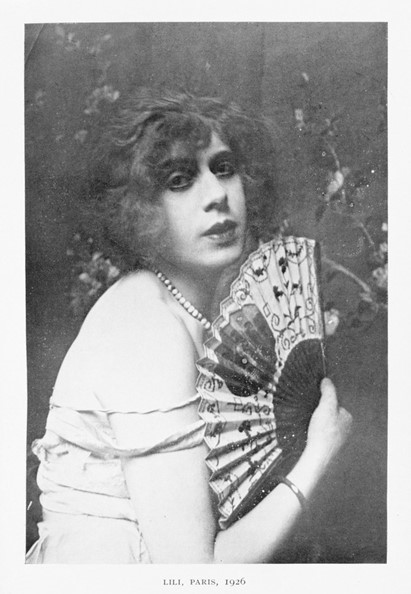

The most famous patient at The Institute for Sexual Science was the Danish painter, Lili Elbe (whose life story is depicted in the film The Danish Girl.) During her year as a patient, Elbe underwent five surgeries performed as part of her male-to-female transition. Unfortunately, she would not survive the process, dying of infection-related complications after her final surgery in 1931.

The Institute offered double mastectomy surgery for trans men wishing to remove their breasts. In 1926, 16-year-old Gerd Katter underwent a full mastectomy at the Institute after he had tried unsuccessfully to conduct the surgery on himself. The gender affirming care he received at the Institute was lifesaving.

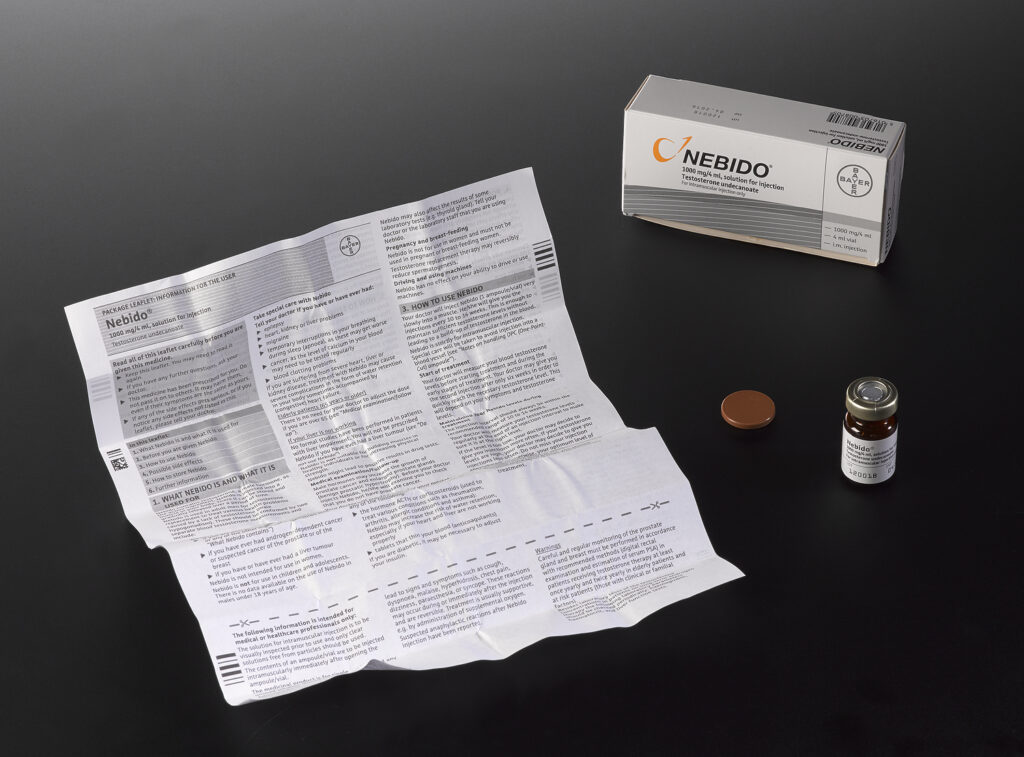

The Institute also offered hormone therapy to transgender patients. Oestrogen allowed trans women to grow natural breasts and develop softer features.

Testosterone was not synthesised until 1935 and was not used medically until 1939, so it was not yet an available treatment for trans men at the Institute. In addition to medical interventions, Hirschfield provided his patients with counselling to provide them with support as they navigated their gender identities.

Destruction of the Institute FOR SEXUAL SCIENCE

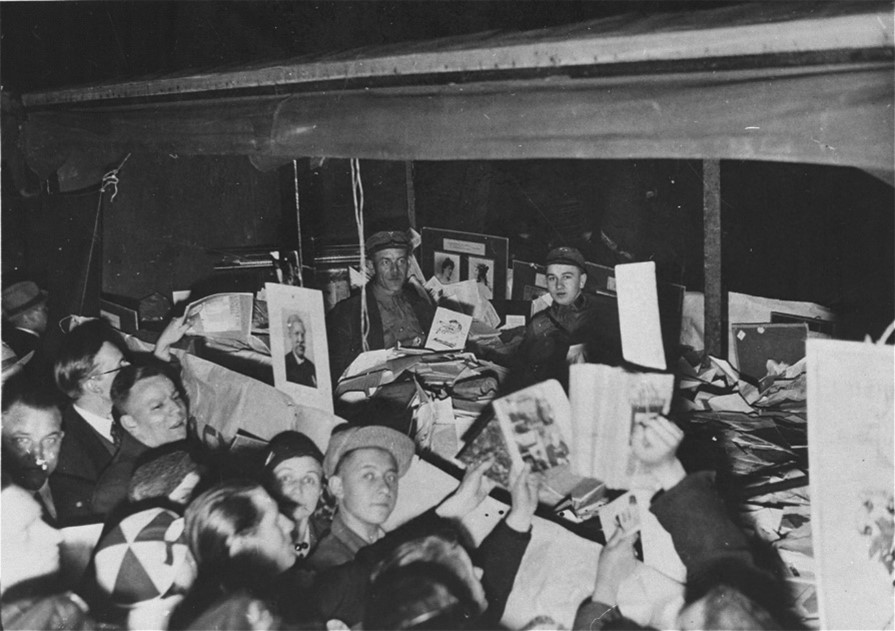

In January 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany. In a matter of months, they began a targeted attack on The Institute for Sexual Science. On 6 May, a collective of Nazi-supporting youths, The German Student Union, occupied the building, looting it of its contents. A few days later, on 10 May, the entire library of the Institute was set ablaze in Berlin’s Bebelplatz Square, along with 20,000 other books considered subversive by the Nazi Party.

Hirschfeld was out of the country on a European seminar tour at the time of the siege. He witnessed the burning of his library from Paris, seeing news reports of the book burning at a cinema. He would never return to Germany. Magnus Hirschfeld died of a heart attack on his 67th birthday in 1935, having spent the last two years of his life exiled in France.

Magnus Hirschfeld’s work with the Institute for Sexual Science is an example of the science and culture destroyed by the Nazis in the mid-twentieth centuries. Fortunately, Hirschfeld’s publications, already widely disseminated across the West, could not be destroyed.

The interdisciplinary nature of these works left a lasting impression on the field of sexual science, influencing later theorists like Alfred Kinsey and Henry Benjamin. His influential theories on sexuality and gender, and the legacy of the gender-affirming healthcare that he provided, have had a significant impact on the field of sexual science and in the lives of queer people.