180 years ago today (12 March 1838), the famous chemist William Henry Perkin was born. To commemorate this anniversary, Sophie Waring, our Curator of Chemistry, looks at items in the collections linked to his most famous invention: mauveine, the first synthetic organic chemical dye.

If you were an average person in the 1850s your wardrobe would have been made up of many shades of beige and browns. Fabric dyes were derived from plants and insects and expensive to make. Colourful wardrobes were a significant symbol of wealth; in particular purples were the often used in the garments of popes and monarchs.

In 1853 the young chemist William Perkin entered the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London, as a student supervised by August Wilhelm Hofmann. A year later, at only sixteen years old, Perkin assembled a laboratory at his home on Cable Street in east London where he started independent research. Perkin sometimes collaborated with Arthur H. Church, a talented painter who was interested in the chemistry of paint.

By 1856 Perkin had become Hofmann’s assistant and Hoffmann challenged him to synthesize quinine, an expensive natural substance much in demand for the treatment of malaria. Perkin started by reacting a salt of allyltoluidine with potassium dichromate.

The experiment failed. Repeating his method but trying different a salt, aniline, Perkin’s obtained a purple solution while cleaning out the flask with alcohol, which seemed to dye silk very easily. The colour remained in the silk even after washing the fabric.

This was the first aniline or coal-tar dye to be discovered.

Perkin collaborated with his brother Thomas and his friend Arthur; together they carried out further trials on the dye and sent samples to Robert Pullar in Perth, who worked in the family firm of Pullars Dyeworks. Perkin filed a patent for this process (patent no. 1984 of August 1856).

Perkin’s mauveine quickly became popular after he borrowed money from his father to establish a factory, invented a way for the dye to be used on cotton as well as silk and gave advice to the dyeing industry on how this new synthetic dye worked.

Public demand increase when Queen Victoria and Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III were seen in the colour. The Science Museum holds this incredible example of this fashion from the 1860s, and a sample of mauveine dyed fabric supplied to Queen Victoria.

After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dyes appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe. In the pursuit of more and more colours German and British dye manufacturers pushed at the boundaries of chemical knowledge and the experimental work of the dye industry is closely linked to developments in medicine and pharmaceuticals.

Perkin’s synthetic colourant was a gateway, leading to the emergency of the synthetic dye industry. This is a celebrated historical story that focuses on firsts, in an industry that produced a rainbow of fantastic colours; mauve has become famous because it was the first synthetic dye. Historians of science have often debated the value of the first, the premier discovery.

Often, later variations of an original discovery or invention prove to be most effective or long lasting; a more potent strain of the penicillium mould was sought and found by an American nurse after Alexander Fleming’s original discovery. Even the most famous of natural philosophers Galileo and Newton fought for the recognition of being the first to discover and invent. The race to discover the structure of DNA was so fiercely run because being the first to declare the structure would insure a place in history. The scientists that worked on Watson and Crick’s description, establishing the arguably more important knowledge of how DNA codes for proteins are not household names. Historians of science work hard to discover these hidden scientists and technicians.

This obsession with premiership extends to museums and their objects.

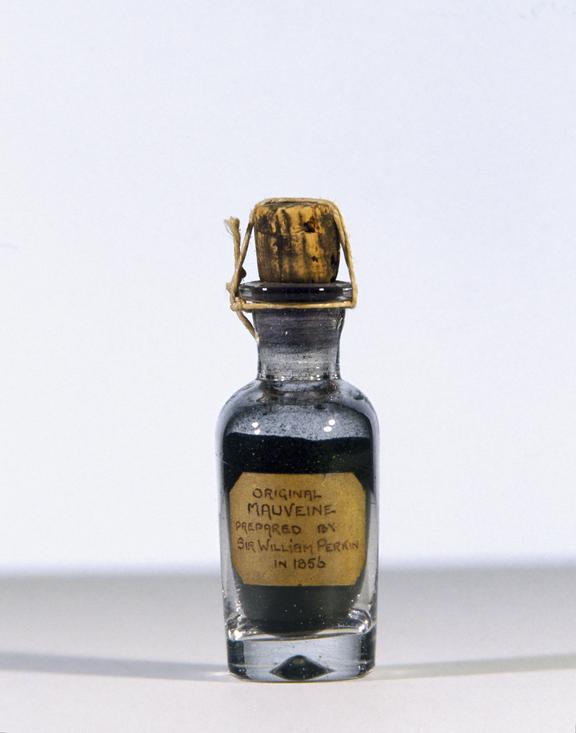

The Science Museum collection holds some of the first samples of mauve produced by Perkin. Chemical analysis on our dyes and textile samples show that our ‘original mauveine’ was most likely not prepared in 1856 as it’s labelled, but is from a 1906 batch made to celebrate the jubilee of Perkin’s accidental discovery.

Does this diminish the object’s importance? Perhaps it adds another layer to the history? The shawls in our collection were dye with Perkin’s original 1856 mauveine formula and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1862. Should our historical attention shift to these textiles? These objects remind us that focusing on the person or object that came first can sometimes frustrate the efforts of historians to understand the past.