Since 2003 November has become associated with an array of magnificent facial hair, as volunteers growing their own moustaches raise money for charity Movember, helping to raise awareness of medical issues related to the penis, testicles and prostate.

Here at the Science Museum, part our collection tells the story of how phallic images influenced medicine and science and particularly how Greek and Roman phallic objects played complex roles in health and public welfare.

Greco-Roman anatomical votives come in many forms and materials and depict a wide variety of ailments. Typically, in the ancient Greek tradition these votives were dedicated to the god Asclepius or goddess Hygeia and were used as offerings to cure sickness.

After a series of rituals including the burial of a votive, patients would sleep for a night in the temple of Asclepius and hope for a dream of the god or a snake that would cure them of all kinds of illnesses, ranging from the plague to a fractured bone. Alternatively, after a successful cure, anatomical votives might be offered to the relevant deity as an expression of thanks.

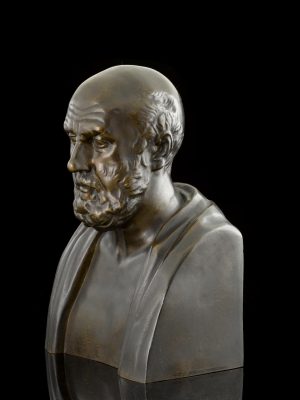

However, alongside this religious and ritual-based healing, specifically in the classical Greek period (circa 5th century B.C.E.- 4th century B.C.E), the Hippocratic tradition emerged.

Hippocrates and his followers advocated for medical practice based on reason and the observation of natural processes rather than the idea that disease and injury were purely the results of divine intervention. This principle, and the promise to do no harm, (the ‘Hippocratic Oath) continues in medical practice to this day, and many celebrate Hippocrates as the ‘Father of Modern Medicine.’

For many ancients these two options were not mutually exclusive. Why not hedge one’s bets and visit both physician and temple?

The intricate details of specific disease were added to anatomical votives in both sculpted and painted designs. These artistic additions suggest that there was crossover between the Hippocratic method of studying illness and the more ritualised faith healing approach taken in the temple.

Anatomical votives, therefore, can illustrate complex ancient understandings about the human body, health, and medicine to modern viewers.

Phallic votives played a large part in the temple healing tradition and today they are a useful archaeological diagnostic tool to explore what worried ancients the most about their health.

In the case of phallic objects, the most common condition depicted was phimosis – a condition in which the foreskin is very tight and can cause pain and infertility to the person affected. While phimosis is a specific ailment, it might also be a clear way of illustrating multiple issues related to sexual organs.

It is likely that people of all genders would dedicate these phallic votives – perhaps because they came to represent fertility more generally. In fact, this practice continued well into the eighteenth century in Italy according to contemporary accounts.

Other sexual and fertility related organs appear in these votive burials including objects representing breasts, vulvas, vaginas, ovaries, placentas, and uteri – though it is important to note that many votives described as ‘wombs’ may instead be representative of ‘vessel’ organs including bladders and prostates.

Different locations across the ancient world had pockets of phallic or gynecological objects, suggesting that there may have been ‘specialist’ temples for different types of diseases. For example, lots of phallic votives have been found in the outskirts of Corinth, perhaps due to the large number of brothels in the city and subsequent issues relating to STIs.

In other ancient Mediterranean cultures, such as the Roman Empire, the role of the phallic object became even more complicated. Votives continued to be used in ritual healing temples and the phallus in this context generally represented of flaccid, afflicted bodies.

Phallic amulets, however, had a very different role and were usually depicted as oversized and erect – sometimes disembodied but equally shown attached to figurines of deities, mythical characters, and humans. These apotropaic phalluses were closer to a kind of preventive medicine – in short they were tools to ward off bad luck and to avert accidents, injuries, and illnesses.

In his work Natural History, Pliny the Elder (c. 23/24-79 C.E.) names these amulets medicus invidiae or ‘doctors against the evil eye’ and describes how phallic charms, or fascinum, were given to male children to keep them healthy during their early years of life.

Pliny also states that the worship of the divine phallus was considered to be of civic importance to the Romans, so much so that it was the responsibility of the Vestal Virgins to properly worship the fascinus (the Latin word for the divine phallus) in order to keep the Roman Empire thriving. Generals would adorn their horses with phallic charms, bringing luck on the battlefield and protecting them from injury.

These apotropaic phalluses were added to architecture as decoration in places associated with danger. In particular, phalluses regularly adorned street corners, doorways, mile markers for weary travelers, and areas where injury, violence, and infectious disease might easily be found – including bath houses and brothels.

However, Romans naturally wanted safety in their own homes as well. A phallic wind chime, or tintinnabulum, was extremely popular for home décor as bell ringing was itself believed to work as protective charm.

If you ever feel yourself wanting to giggle at these amulets and art works, feel free! In fact, laughter was another sound that could repel the evil eye and some phallic objects may have been deliberately made to cause a viewer to laugh out loud.

The addition of satyrs, nymphs, and other worshippers of Dionysus/Bacchus (the god of wine) often makes phallic images funnier as we are invited to partake in the tricks and antics of Bacchic revelers.

Phallic figures are often represented as dancing, laughing, lounging, and even passed out drunk from the shenanigans of the night before. Throughout it all, their phalluses are at full salute – erect and continuing to protect the onlooker from jealousy and curses. For the Romans, laughter certainly was the best medicine!

The presence of these objects in our collection underscores the importance phallic objects had in the early practice of medicine. Phallic imagery played a complex role in the ancient Greco-Roman world.

In one form a phallic votive reflected a specific illness and was a tool for seeking improved health. The same object to another person might be a means of thanking a god for granting health and good fortune. The phallus was also understood as a powerful tool to protect yourself – and all of society – from misfortune and ill health.

While it’s certainly good to appreciate the significance that phallic objects have had in the history of medicine, today it is also crucial to take the time to practice some preventive medicine yourself. For those who have them, make sure to get checked for prostate, testicular, and penile cancer this Movember. Find more information and get support on the Movember and Prostate Cancer UK websites.

Further reading

Clarke, John R. Looking at Laughter: Humor, Power, and Transgression in Roman Visual Culture, 100 B.C.-A.D. 250. Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2007.

Johns, Catherine. Sex or Symbol: Erotic Images of Greece and Rome, 2nd ed. London: The British Museum Press, 1989.

Petsalis-Diomidis, Alexia. “Between the Body and the Divine: Healing Votives from Classical and Hellenistic Greece.” In Ex Voto: Votive Giving Across Cultures, edited by I. Weinryb, 49-75. New York: Bard Graduate Centre, 2016.

Discover more anatomical votives on display in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries at the Science Museum.

Learn more about medicine in the ancient Greek world in our free temporary exhibition Ancient Greeks: Science and Wisdom, open until 5 June 2022.