Though not the first cloned animal, the dogma of the day’s biology said that the cellular clock could not be turned back once embryonic cells had differentiated into stem cells and then hundreds of other cell types in an adult body, from brain to muscle cell.

Dolly, the Finn Dorset sheep, born in 1996 in the Roslin Institute, south of Edinburgh, became a media sensation (the BBC shared reflections on the news in 2021).

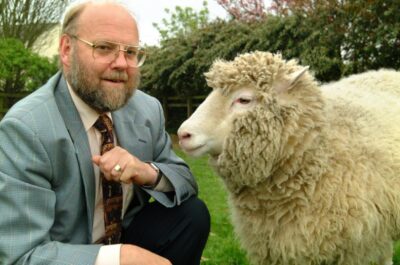

Though the feat was greeted with initial scepticism, notably in America, the media sounded the alarm over the implications: ‘Cloned Sheep in Nazi Storm,’ ‘Dolly Opens Door for Life after Death,’ ‘The Clone Rangers Need to Be Stopped,’ and ‘Golly, Dolly! It’s the Abolition of Man.’ But journalists expecting to meet a wild-eyed Frankenstein were instead confronted with the genial and softly spoken figure of Ian, in wool sweater and, as one paper put it, with ‘the face of a bank clerk’.

Wilmut and his colleagues had used the method of nuclear transfer, a technique conceived in 1928 by German embryologist Hans Spemann (1869–1941), working with Hilda Mangold, which involves taking the DNA from the compartment at the heart of an adult cell, called the nucleus, and transferring it to an egg cell that has had its own nucleus removed.

In 1989 Wilmut and Lawrence Smith, a doctoral student at Roslin, generated four cloned lambs with nuclear transfer. Importantly, their work suggested that the sequence or cycle through which each cell progresses from one cell division to the next was important, an insight that would be deepened by Keith Campbell whose knowledge of the cell cycle proved critical for the cloning of Dolly.

They first realised it was possible to clone differentiated cells in 1995, with the two cloned Welsh mountain sheep, Megan and Morag. The following year the large Roslin team, working with the company PPL Therapeutics, used mammary gland cells from a six-year-old ewe as nucleus donors for transfer into egg cells. The large team made 277 embryos this way, implanted them into 13 surrogate mothers, only one of which became pregnant.

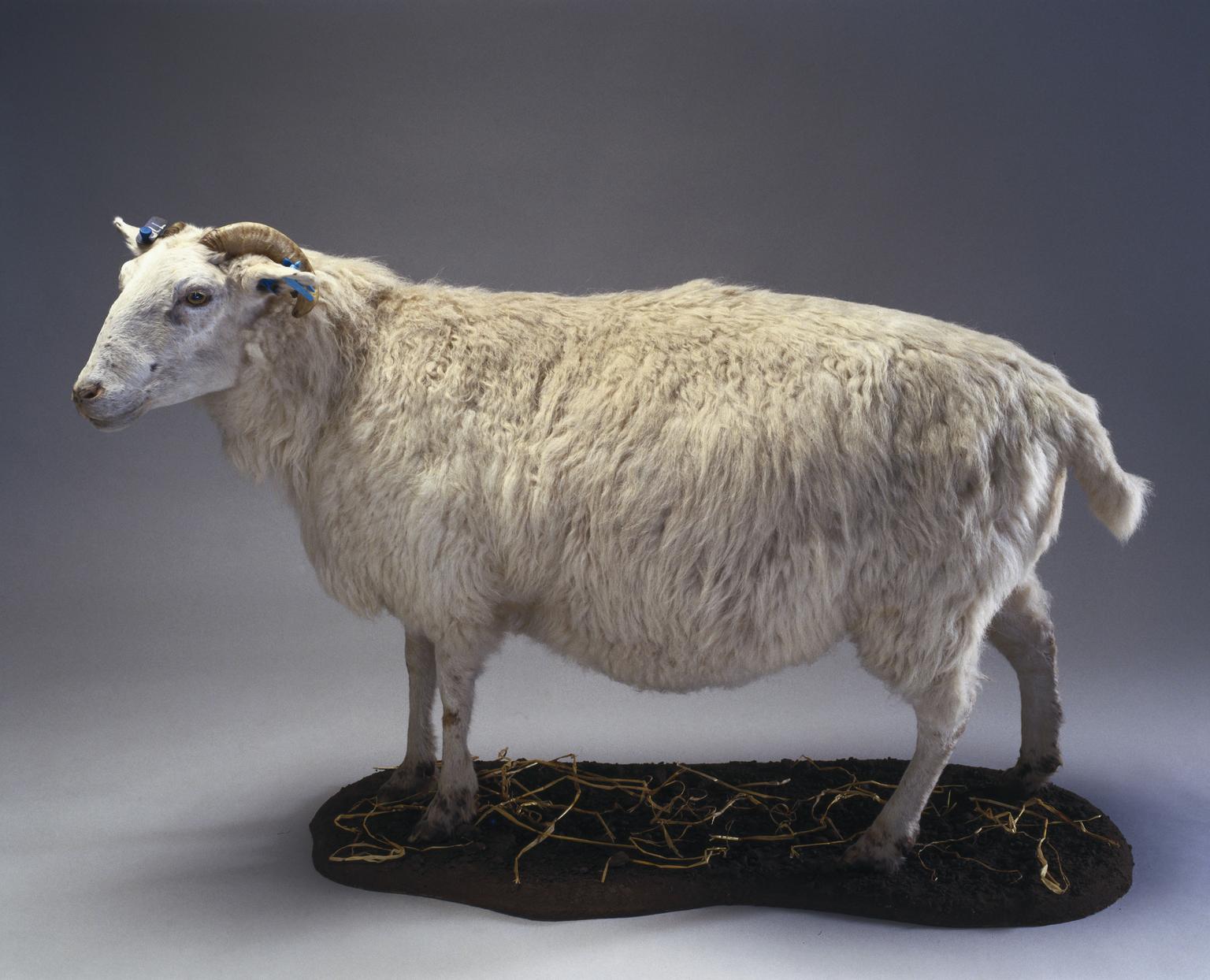

The resulting 6.6-kilogram lamb, born on July 5, 1996, was Dolly, named as a tribute to the American singer Dolly Parton.

Though the feat opened up new possibilities for stem cell science and genetic modification, popular interest focused on cloning people. Wilmut was deeply opposed for ethical reasons, not just the psychological impact of cloning but because the process was so inefficient and led to defects.

Ironically, the work on cloning was aimed at developing an efficient way to genetically modify an embryo before it is implanted in a surrogate mother.

The idea was to find a more efficient method than the one that had led to the generation of a sheep named Tracy, created from a fertilised egg that had been genetically engineered through DNA injection to produce milk containing alpha-1 antitrypsin, a human enzyme used to treat cystic fibrosis and emphysema.

The sheep, which Wilmut called ‘a living drug factory,’ is now in the collection of the Science Museum Group, alongside a jumper made from Dolly’s wool.

In 1997 Wilmut and his colleagues unveiled Polly, a Poll Dorset clone created by nuclear transfer using foetal cell nucleus genetically engineered with a human gene for human factor IX, a blood clotting factor absent in people with haemophilia, an advance in what was known as ‘pharming.’

The interest in using cloning to make stem cells for treatments – therapeutic cloning – was intense in the wake of Dolly’s birth. However, in 2007, Ian Wilmut decided not to pursue a licence to clone human embryos as part of a drive to find new treatments for the devastating degenerative condition, motor neuron disease.

The reason was that a rival method to genetically alter cells, developed by Shinya Yamanaka (which would earn a Nobel prize in 2012) had more potential for making human embryonic cells, to grow a patient’s own cells and tissues for a vast range of treatments, and without the ethical concern about cloning and dismantling human embryos.

In 2005 Ian Wilmut accepted the chair of reproductive science at the University of Edinburgh, though still maintained his relationship with the Roslin Institute. He received several awards, was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2002 and was knighted in 2007.

In addition to papers published in major journals such as Nature and Science, he wrote The Second Creation: Dolly and the Age of Biological Control (published in 2000, with Keith Campbell and Colin Tudge) and After Dolly: The Uses and Misuses of Human Cloning (2006, with Roger Highfield).

After a long illness, Sir Ian died on the morning of 10 September 2023. Five years ago he revealed he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s and had told one interviewer that though work with Dolly would accelerate research in the field ‘people like me will probably have died of Parkinson’s disease before the new treatments become available.’

Many senior figures have reacted to the news of Ian Wilmut’s death. Prof Bruce Whitelaw, Director of the Roslin, said that science ‘has lost a household name’, while Prof John Iredale of the University of Bristol, who worked with Ian Wilmut, talked of how he was ‘scientifically brilliant and shrewd and possessed of warmth and great humour’. Prof Sir Peter Mathieson, Principal of the University of Edinburgh, said: ‘He was a titan of the scientific world.’