When fine porcelain bowls and teacups from the eighteenth-century are displayed and preserved in the collections of museums and country homes, they speak to us of many things: art and design, society and empire, perhaps even our own tea-drinking habits.

Chemistry is probably not high on the list of things that come to mind when looking at porcelain and china, but this teacup is very much at home in the Science Museum Collection as an object that tells us as much about scientific innovation as it does about the imperialist tea-trade or the tastes and values of eighteenth-century society.

Between 1712 and 1720 many of the manufacturing secrets of Chinese porcelain were revealed to European audiences for the first time through the writings of the French Jesuit father Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles who lived in Jingdezhen, the centre of porcelain production in China for over a millennium. While this information flowed from the east, the Germans Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus and Johann Friedrich Böttger had independently discovered the secret of hard-paste porcelain manufacture in 1710, establishing the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory near Dresden.

English manufacturers were behind. The first soft-paste in England was only demonstrated in 1742 by the chemist Thomas Briand to the Royal Society. In contrast to the hard-paste porcelain fired at high temperatures which was being manufactured in Germany and imported from China, Briand’s soft-paste porcelain did not easily retain its shape in its wet state, and slumped in the kiln under high temperatures. This also meant the glaze could be easily scratched. Nevertheless there was a rush of porcelain manufacturing following Briand’s method; the Chelsea Porcelain Factory and the Bow Porcelain Factory in London, where the first factories were founded, started traditions in this period that still define their signature designs today, such as Wedgewood and Spode.

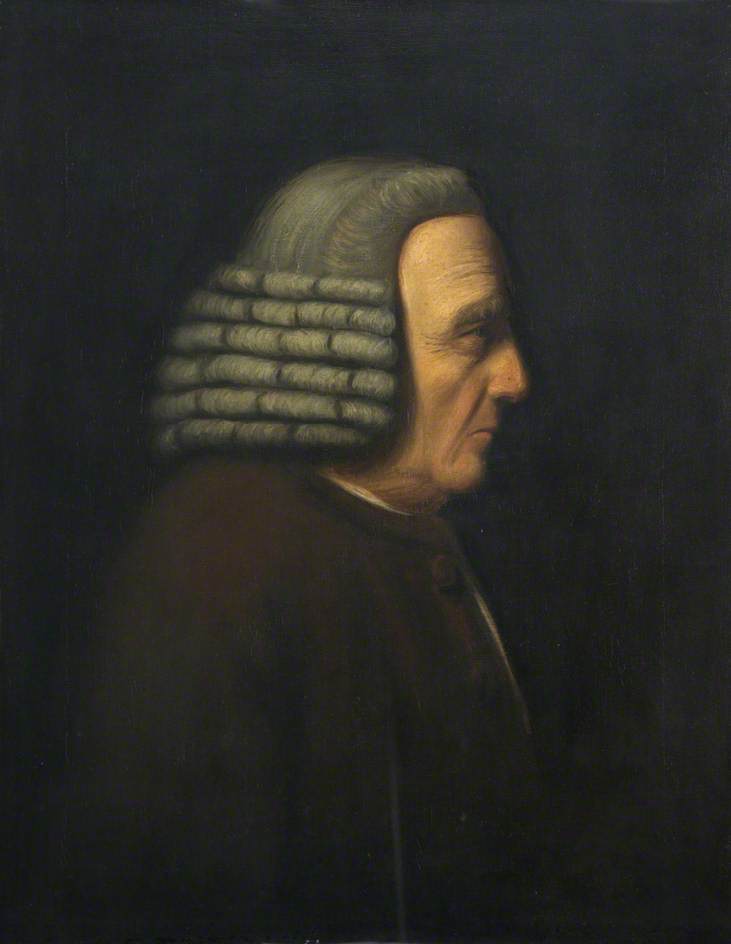

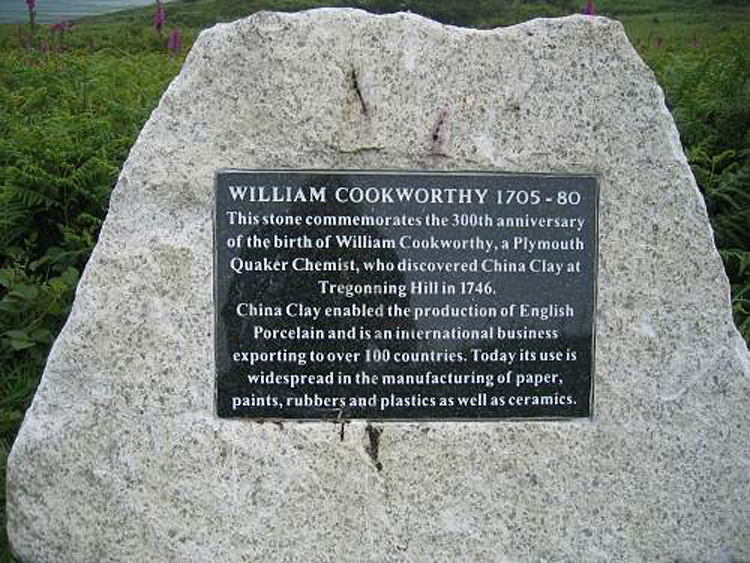

One of these early factories was different. Plymouth Porcelain, established in 1769 used kaolin and ‘china stone’ to make hard-paste porcelain similar to Chinese porcelain imports of the early 18th century. This factory was established by the chemist and Quaker minister William Cookworthy.

Cookworthy began an apprenticeship with the Quaker apothecaries Timothy and Sylvanus Bevan in Plough Court, London. Cookworthy, coming from a poor part of rural Devon, walked to London, saving the coach fare, to start work at age 15. Quickly recognising his outstanding intelligence and practical skill, the Bevan brothers took Cookworthy into their partnership at the end of his apprenticeship in 1726 and formed ‘Bevans and Cookworthy’, a wholesale chemist and druggist in Plymouth, servicing the west-country doctors and the navy at the port.

After the death of his wife Sarah a decade later, Cookworthy retreated entirely from public life leaving his brother to manage his business. He devoted his energies to walking, religious work and began experimental work with clay.

Cookworthy quickly realised that two key ingredients of Chinese porcelain – kaolin for the body and petuntse for the glaze – were to be found in the china clay and moorstone (called locally: growan) in the Cornish moors.

By 1758 he was successfully firing hard-paste porcelain, but the discovery of abundant deposits of high-quality china clay and moorstone on the estate of Thomas Pitt, later Lord Camelford, allowed Cookworthy to think of factory scale production. Pitt financed Cookworthy’s continuing experimental work and in 1768 helped him obtain a patent, to protect his method in a competitive market.

In the same year, Cookworthy opened a porcelain factory in Plymouth. This quickly cemented Cookworthy’s position as a significant member of intellectual society, with John Smeaton choosing to lodge with him during the building of the Eddystone Lighthouse, and Captain James Cook, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander all dining with him before sailing from Plymouth in 1768.

The business moved to 15 Caste Green, Bristol, where porcelain was manufactured under Cookworthy’s supervision until his retirement in 1773. His partner Richard Champion bought Cookworthy’s half of the business and the rights to his patent, but only continued production until 1778. Champion sold the method and the factory to a syndicate of Staffordshire Potters who used Cornish clay to make bone-china. The true porcelain manufacturing method, invented and pioneered by Cookworthy, virtually ceased in Britain after the closure of the Bristol factory.

Bristol porcelain is displayed by many art and design collections in the UK, appreciated for its elegance, but with this teacup held by the Science Museum we can remember the link between the art and science of innovation in the Georgian period; materials and design affecting each other, with hard-paste porcelain allowing Cookworthy to produce items rivalling those from Jingdezhen, something his British counterparts could only try to imitate 250 years ago.