As a Curator and once a member of the clock-winding team at Royal Museums Greenwich, I have had the privilege of spending time with Harrison’s portraits and his timekeepers on a weekly basis. So, it’s been a pleasure to keep my connection with this familiar face, and to start to think about Harrison in the context of the SMG collections.

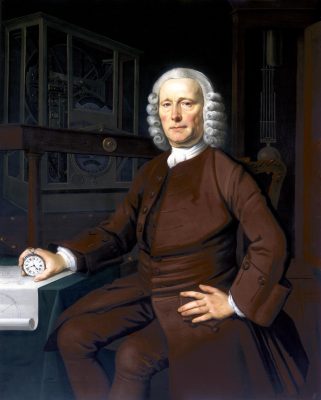

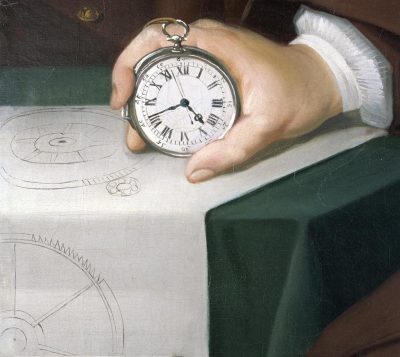

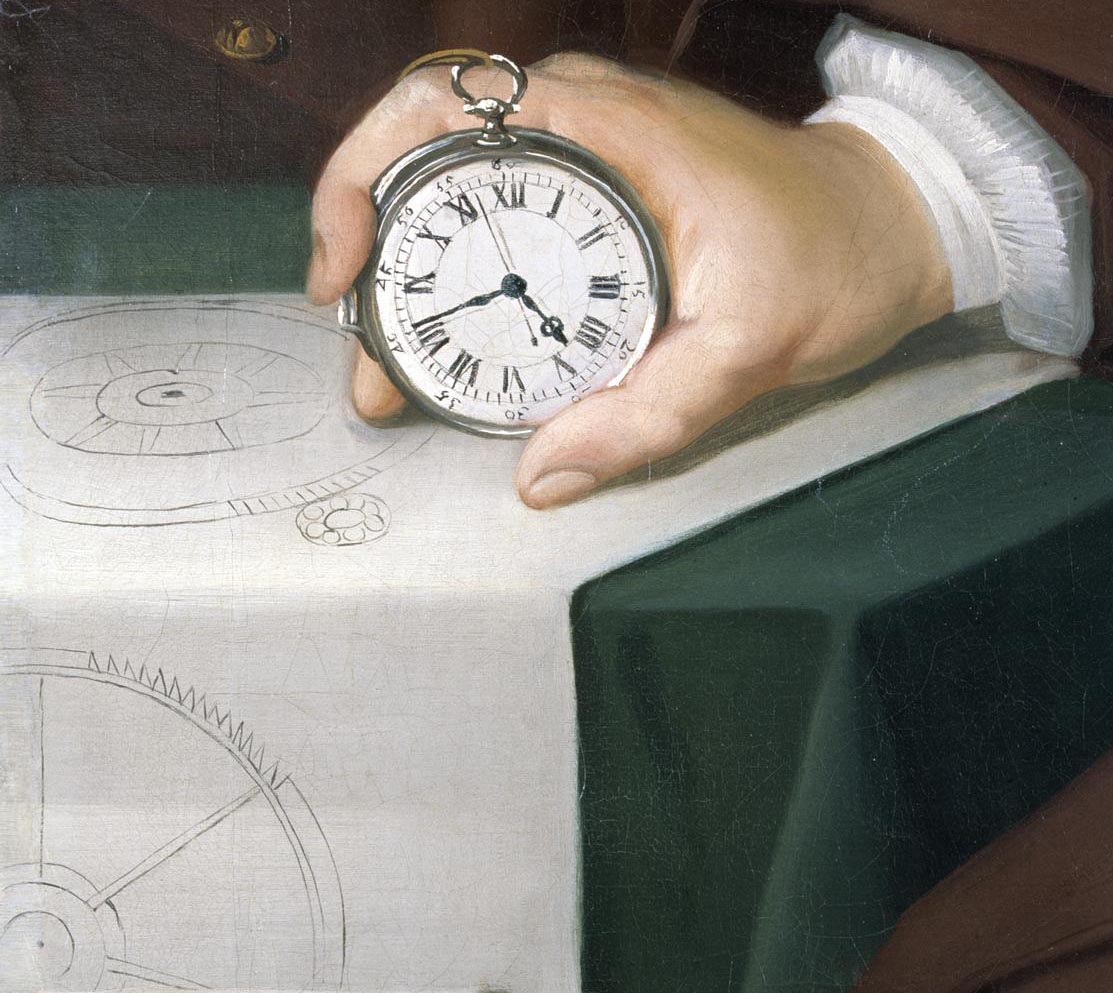

Harrison’s portrait was painted by Thomas King in about 1767. It is as much a portrait of his inventions as of the man behind them. He sits confidently at the centre of the picture, right hand resting on a table and holding a watch made to his design by watchmaker John Jeffries.

On the table lies a page of drawings of clock parts, and at each shoulder stand two impressive machines: on the left his third marine timekeeper (now known as H3) in its travelling case, on the right his compound pendulum, designed to compensate for metal expansion and contraction in different temperatures at sea.

The portrait assembles Harrison’s arsenal of material proofs against the Board of Longitude. The Board was arguably the first government science funding body, established in 1714 to find a means of measuring longitude accurately at sea, and adjudicator of large reward money for the solutions. By 1767, when this portrait was painted, Harrison had spent over 30 years in discussion with the Board, receiving sequential funding to develop a series of timekeepers.

In the 1760s, their relationship had become increasingly strained around the question of whether and how Harrison had fulfilled the terms necessary to receive the ‘great reward’. In 1767 the Board published the Principles of Mr Harrison’s Timekeeper, essentially to see if his designs could be replicated by other clock and watchmakers. A similar page of designs lies under Harrison’s hand on the table in his portrait.

King’s confident portrait belies a sitter both bullish and plaintive in pursuit of his dreams. Harrison’s published pamphlets and correspondence with the Board show a man convinced of his machines but struggling to communicate them in a way that others could understand.

Both the portrait and the engraved plates of the Principles were forms of visual capital that offered one means to do so. Within the Science Museum collections, Harrison joins a group of portraits that similarly allow us not simply to see what men and women of science looked like, but to begin to unpick how their image was formed.

One comment on “A portrait of Mr Harrison and his timekeepers”

Comments are closed.

Welcome back to the world of #histSTM blogging. You’re off to a flying start.